The club space. The dance music lover’s tabernacle. It’s the type of establishment that is regularly under constant threat of closure in many places. But it’s here in London that these confrontations seem more palpable and strenuous than ever. An ongoing tug-of-war between club owners and property developers has raged on for as long as we can remember, but came to a head most recently when South London venue Bussey Building was targeted by the local authorities. Not only is Bussey considered one of the most treasured nightclub spaces, but it also facilitates a thriving community of DIY-ers who depend on it as a workplace and networking hub. Luckily, the plans to turn the Peckham spot into faceless, über-expensive housing fell flat. But this latest attempt has highlighted just how important the permanent club space really is.

Read on as Jake Hulyer speaks to a number of veteran nightclub figures including reps from The End, Corsica Studios, the Blue Note and more to observe that fact.

—

A lot of things need to come together for a party to really work. There’s the music and the crowd, of course, but all kinds of other details elevate a night to being something properly special. Getting those small things right – the sound, the layout and even the toilets are what aid those indefinable kind of concepts like a feeling or a vibe. Loose, vague ideas, it’s in those terms which we talk about those nights which burn longest in the memory. And it’s often the places that go the extra mile, having a clear vision for their space, that attract the kind of cross-section who’ll come together to make that happen on a regular basis.

For a group of architects working under the umbrella of Radical Design in late 1960s Italy, designing and creating spaces was a vehicle for realising their vision of what nighttime experiences should be. Explored in a new exhibition at the ICA, the clubs – or pipers as they were known – are notable as some of the few built examples of so-called radical architecture. Often interdisciplinary spaces that showcased the more experimental sides of music, art and film, they were created to incubate creativity as well as counteract the the social injustice and creative restrictions which were commonplace outside their doors. But the political reality they set themselves in opposition to soon crept inside, with most changing hands or being converted into commercial spaces by the mid-1970s.

Credit: BMIAA

It’s a shift with parallels in London’s solemn trudge toward homogenisation in 2015. Recent high profile closures, both forced and voluntary, have switched on a lot more people to the importance of the permanent venues we have in the capital. Though London’s clubs might not have been created in the same radical fire of 1960s politics, the argument – between the creative and the commercial – is a similar one. Usually converted from ex-industrial or derelict properties, the impetus to create a place where friends can meet and dance is its own kind of rebellion. Shouldn’t there be room for spaces that harbour subcultures, weirdos and the alternative to open their doors as nearby offices and shops shut theirs?

Property developers, who by and large view clubs as occupying prime retail space better-suited to housing a new branch of Itsu, are knocking up luxury flats at a rate which feels increasingly out of control. You don’t need to look further than the very recently dropped proposals in Peckham, which would have all-but-spelt the end for the Bussey Building, to see how easily regular spots can suddenly vanish. It’s prompted a more concerted effort to make the case for clubs as social hubs which hold a real cultural importance.

“I just made sure that everyone felt it was their place.” Sav Remzi (Blue Note)

It’s with this in mind that we’ve spoken to a number of influential venues to understand what it is that can be so special about groups of people meeting in darkened rooms each weekend. Meeting with Sav Remzi, manager of the Blue Note throughout its short-but-influential lifespan from 1993 to 1996 (excluding an unsuccessful relocation to Islington), he recalls how “there was no master plan” for the way the East London spot developed. “It was an accident,” he says. “It was just a place for lots of likeminded people to come together and exchange ideas, which is the definition of what a club is: an organisation of likeminded people.”

As well as the much-eulogised Metalheadz party on a Sunday night, they held residencies from the likes of Ninja Tune, Mo Wax and Talvin Singh’s Anokha. He explains how a smaller, less fragmented dance community was part of what helped to make the place so magical. “Nowadays the promoters are venue-hopping. They’re not making anywhere a home, you know. Clubs used to be a place you could go almost every night and find something new. At the Blue Note, I used to spend three or four nights a week there. I just made sure that everyone felt it was their place. And then, you know, you get Grooverider pressing an acetate and bringing it straight down to Metalheadz on a Sunday night to see how it works in the club. Or people jumping off the plane from Japan to come down to Gilles [Peterson’s] night on a Saturday.”

The same familial atmosphere is evident inside the South London railway arches where Corsica Studios have made their home. Following tenancies in different properties and arches centred around King’s Cross – hosting artists, rehearsal studios and private parties – it was after settling in Elephant & Castle in 2001 that those parties began to happen more regularly. It was from there that co-founders Amanda Moss and Adrian Jones’ space developed its current focus on nightlife. “Those early parties,” Jones recounts, “were invite-only, groups of friends, extended circles of friends, labels. They were literally people with books of tickets selling them to their mates, with maybe a few in Phonica or whatever.”

It was a lot of the promoters organising those early get togethers, many of them local students to begin with, that they later hired to work on in-house nights like Trouble Vision and Tief. “Those early parties were very intimate. And they were fantastic, because everybody knew each other,” Jones says. “It’s been an organic evolution of our interests and our circle of friends, introducing other people to us who they believe would get where we’re coming from musically and ethically.”

Making long term connections, both local and further afield, has been important to Dance Tunnel too. As Matt Wickings, programmer at the three-year-old Dalston basement explains, “We just book who we like. We’ve just stuck to that pattern, and we tend to invite a few guests back every year.” Panorama Bar resident Tama Sumo holds her Your Love parties there four times a year, while East London locals Jane Fitz and Francis Inferno Orchestra are set to begin similar arrangements soon.

But whatever the values underpinning a place, having a space to imprint that ethos upon seems vital. Modelling somewhere in contrast to the issues in most London clubs in the 1990s was a shared motivation between Remzi and The End co-founder Mr C (aka Richard West). Ice cubes turn out to be a recurring symbol of their bad experiences. As Remzi unhappily remembers, “The cheap clubs, man. The attitude was just, ‘We’ll put a couple of buckets of ice behind the bar and get some students to serve them.’” And as West recounts, “The West End clubs were awful. You’d buy a drink and there’d be like one cube of ice if you were lucky.” For both of them, it was simply one of the many aspects they felt you had to get right when setting up a place.

The End, running from 1995 to early 2009, was founded by West and Layo Paskin, with Paskin’s father an architect who managed the extensive renovation of what had originally been a part of the Post Office’s underground transport network. Along with a properly stocked bar and decent toilets, the hydraulically sprung floor, lighting rig and impeccable soundsystem would, West argues, “become the blueprint for clubs in modern day London.”

“It’s really important to do something where you don’t need to know what’s on, you just know it’s going to be good.” Matt Wickings (Dance Tunnel)

And while the story of its creation appears detached from politics in comparison to the Italian pipers, that’s not to say it doesn’t offer a different form of quiet resistance. Building a space that allows people to really escape, in contrast to sub-standard alternatives which “were mostly built by business entrepreneurs”, is radical in its own way. Indeed, it’s surely not an accident that the Blue Note was set up by Acid Jazz label head Eddie Piller, that Dance Tunnel’s three owners include DJs and promoters Dan Beaumont and Matt Tucker, while Corsica Studios’ founders’ come from backgrounds in art and music. They all are or were commercial establishments, of course, but there’s something that goes beyond looking at the bottom line behind the decision-making in all of those places. That care for the extra details: hiring friendly staff, tweaking the sound and working with music you’re passionate about, is what attracts a loyal crowd who recognise that ethos.

Corsica Studios’ renovation was informed by their own idea of how those liberating possibilities work. “The idea was that it’s open to interpretation, in a way,” Jones explains. “Different people can come in and configure it how they need. We haven’t been particularly fussy about the furnishings or the decor. If you want to hammer something into the wall, that’s okay, you know.” And, as Moss continues, “That gives people freedom, which is what people need to live happily and with fulfilment. So if you can create a space where people feel that they are free to express themselves, to a certain limit without harming anybody or themselves, then I think that that’s good.”

“When you’re feeling everything, when the system’s tuned properly, the room’s treated properly, everything locks into place.” Adrian Jones (Corsica Studios)

The stripped back aesthetic is in a different mould to The End, but getting the basics right is still just as important to them within the blank canvas that they offer to people. “When you’re feeling everything, when the system’s tuned properly, the room’s treated properly, everything locks into place,” Jones argues. “When you’ve got the right music, the right energy, the right sound, it doesn’t matter what the lights are doing, what the wallpaper’s doing. Everything is uplifted.”

In the unassuming ideals guiding Dance Tunnel, too, there’s a similar form of quiet resistance being enacted against the outside world. “I don’t think we ever saw ourselves as much more than just another club down the road,” Wickings says. But in its simple dedication to providing a dark basement for you and your friends to go and dance in, it’s still an escape from the kind of values that govern most other parts of everyday life. The sound, the music and the people which those things invite to make their way down the stairs week after week are what make a basement club special. And he explains how keeping half the tickets on the door and having £5 entry before 11 every Saturday has helped to maintain a regular crowd. “We have a nice community of people who come down every week. There’s always a lovely couple there who are there in the booth every Saturday.”

It goes back to the idea, raised by Remzi, of what makes a club. In a context where the place of weekly clubnights has been overshadowed by the ascendence of yearly festivals, there’s also been a noticeable shift in the way that a lot of promoters are now selling tickets. It’s increasingly commonplace to see tickets with tiered price bands onsale way ahead of time, making it more and more normal for people to plan their Friday night out two months in advance. “They’re more like events, they’re not clubs,” Remzi argues. “Putting on a couple of DJs and charging an entry fee, it doesn’t make a club. We’ve talked about what makes a club, it’s the eye-to-eye contact.”

It’s the continuity allowed for by affordable tickets available on the night, Wickings argues, that makes a small-but-significant difference. “There’s lots of good parties who focus on advance tickets, that’s fine, but there needs to be something else on offer,” he argues. “We always keep half on the door to keep it more casual. It’s really important to do something where you don’t need to know what’s on, you just know it’s going to be good.” Inviting and keeping hold of a regular crowd is important in two ways: it retains that all-important social intimacy and it in turn gives you a platform to do something a bit different, able to resist the safe route of identikit DJ bookings.

“Some of the events that you go to where there isn’t an inner circle like that, it’s because these promoters are just glorified booking agents putting on big name DJs.” Mr C (The End)

And even though West is now putting on his Superfreq parties outside of his club where they were started, he says that the way nights are programmed has taken on a greater importance at a time when most people are “crowd followers rather than music followers”. This means “promoters are going to have to actually promote,” he argues. “It’s about having a party. When you can sense that there’s a certain familiarity, that there’s an open minded inner circle of people open to making new friends, that’s when things are really going to start to gel. Some of the events that you go to where there isn’t an inner circle like that, it’s because these promoters are just glorified booking agents putting on big name DJs.”

But as the squeeze on space gets tighter in London, it’s important to recognise the importance of permanent venues, like The End was for Superfreq, in fostering those circles. “This idea of a gathering of likeminded people through music,” Moss says, “you can have it on a beach, you can have it on a boat. But we do need to preserve these spaces, as it’s there where the centre of the well is coming up.” We’ve reached a time when the well-versed cycle of gentrification – undesirable areas become hub for creatives, more well-to-do move in, new blocks of flats appear, noise complaints signal end of venues which attracted people in first place – seems to be reaching its endpoint. With a distinct lack of downtrodden inner city areas left to move to, it’s becoming more urgent to communicate why these places are valuable.

“It’s absolutely vital that there are spaces for people to celebrate, relax, enjoy themselves, get messed up in, let their hair down, dance, explore the boundaries of creativity,” Jones says. But where there’s no safety mechanism to protect venues which predate newly built flats, the risk is always there there that they will be forced out. “There needs to be changes at the planning or policy level,” he continues. “I’m not saying we’re on the same level as the ENO, but there are significant buildings of all cultures that no one would want to see disappear.”

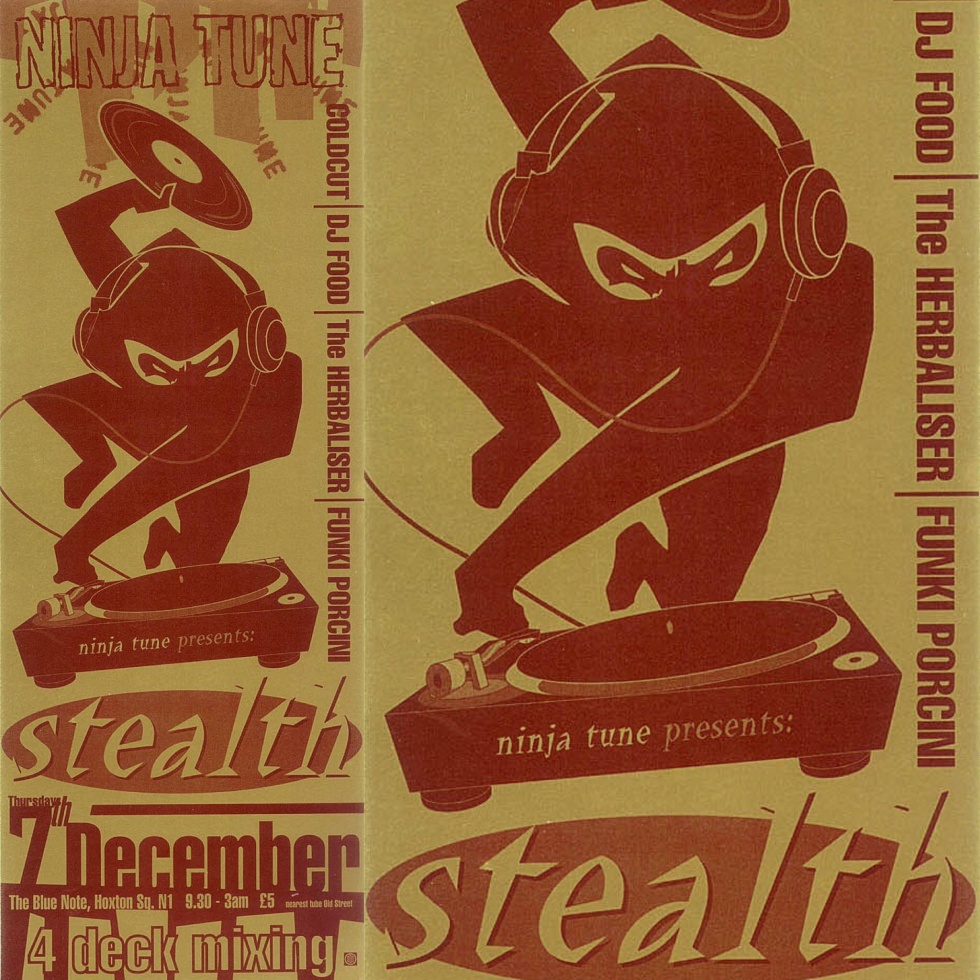

Squarepusher playing at Ninja Tune’s Stealth residency at the Blue Note in 1996 — a young Benji B and Aphex Twin look on. Credit: Martin le Santo Smith

Remzi argues that developers need to incorporate venues into their plans for an area. “They should incorporate purpose-built spaces and venues that won’t affect surrounding neighbourhoods in a negative way. Soundproof it, make it safe, clean, get it proper planning and licensing, and give people a reason to move to an area that’s more than just being near the tube.” That suggestion does, however, rely on a very optimistic view that developers look at an area with more than giant cartoon money bags in their eyes. The policy changes within councils suggested by Jones seem like a safer bet; ensuring that developers either plan new venues or work with existing ones – incorporating them into plans and allocating funds for soundproofing – could be a route to futureproofed nighttime spaces.

There are practical considerations to keeping hold of licensed venues too. If there aren’t regulated venues for people to go to, the illicit ones that take their place would undoubtedly bring far more problems than the nuisance most councillors lament of in the clubs that exist now. As Jones points out, “Whatever the risks there are, they’re going to be massively exaggerated if no one’s taking charge of things and people can just walk away from a situation should it occur. We’re here, open, every day of the week. We’re not going anywhere. It’s in our interest to maintain a safe environment and to do things properly.”

Those sorts of itinerant, illicit spaces could also never have fostered the same kinds of connections that these regular venues have facilitated. In the different residencies spread across the Blue Note’s seven nights, there was inevitable cross-pollination between Ninja Tune’s nerdy breakbeats and Singh’s Asian Underground, and from the jungle freakouts at Metalheadz on a Sunday to Gilles Peterson’s backroom jazzhead roots at his Far East night. “I do wonder what direction music would’ve taken, had it not been there,” Remzi ponders. “It would’ve happened, but not so culturally shared.”

But even the many musical legacies that have undoubtedly gestated within clubs are almost beside the point. The financial argument for the benefits generated by nighttime businesses is a compelling one, too, being well made by the Night Time Industries Association. But that’s also beside the point, which has more to do with what these spaces represent. Set up with the primary aim of bringing people with a shared love of music together every week, it’s easy to forget how amazing an idea that really is. As London becomes a playground for the ultra-rich resembling a dystopian nightmare more with each passing week, as does the significance of preserving that idea become even more pressing.

Of course, the dubiousness of distinguishing between “good” and “bad” clubs is part of the problem in making the case to local authorities about the benefits that some establishments bring versus others. And the adoption of Safe Space policies, by nights like Peckham’s techno hub Gateway To Zen, is also a sign that there plenty of issues around inclusivity and sexism which have not been resolved, wherever the venue. But there’s no better way to build positive, inclusive attitudes than through a space created in collaboration between owners and attendees who share those values.

“At every event here there’s energy that’s created, that’s given out. I’m sure those walls absorb that energy, I’m sure they retain that. It’s like the bricks in the sun, you know, that energy’s retained and that emanates.” Adrian Jones (Corsica Studios)

As Jones says of Corsica, “At every event here there’s energy that’s created, that’s given out. I’m sure those walls absorb that energy, I’m sure they retain that. It’s like the bricks in the sun, you know, that energy’s retained and that emanates. Over the years – the decades – that we’ve been here, there’s a lot of love and energy that’s been absorbed by these arches.”

There are plenty of ways to measure the value that venues can bring to an area and to a musical community, but it’s the vague, slippery ideas you can’t measure – like energy or a feeling – that are the most important. Measuring things by how productive they are in terms of economics, or productivity, leaves you falling into the models prized by the people buying up the parts of London that these clubs find themselves in. It’s the fact that they’re built on a different kind of logic that makes them so special.

—

The Radical Disco: Architecture and Nightlife in Italy, 1965-1975 exhibition is on at the ICA from 8 Dec 2015 – 10 Jan 2016. Head here for more information.