In The Heat of The Club: Madrid’s Reggaeton Explosion

Music projects inspired by reggaeton and trap are bringing together an internet-bred generation.

Over recent years, a new movida has been gaining momentum across Spain. All over the country, young people have been coming together to reclaim venues and turn them into safe, inclusive spaces for creative self-expression. “Everyone’s welcome to the party, so long as they don’t bother anyone,” says Ms Nina, an Argentinian-born internet artist and singer, who moved to Granada from Latin America as a young teenager. Now she lives in Madrid and is one of the most recognised faces of the perreo movement in Spain.

Although she asserts that she’s “no Becky G”, last night Ms Nina performed to a packed-out arena with the legendary electropop duo, Fangoria. More than just a meeting of two very popular entertainers in Spain, it was also a meeting of two very significant countercultural movements in Spain. One half of Fangoria is Alaska, a representative of the Movida Madrileña along with other acclaimed artists such as Pedro Almodóvar and Tino Casal.

The transgressive scene emerged in Madrid as a reaction to the relaxation-followed-by-complete-disappearance of Franco’s censorship laws. The death of the dictator who had ruled Spain for 36 years following the Civil War paved the way for the country’s transition to democracy. Instead of being spurred on by the democratisation of a country, today’s movida has been propelled by another form of democratisation: access to the internet.

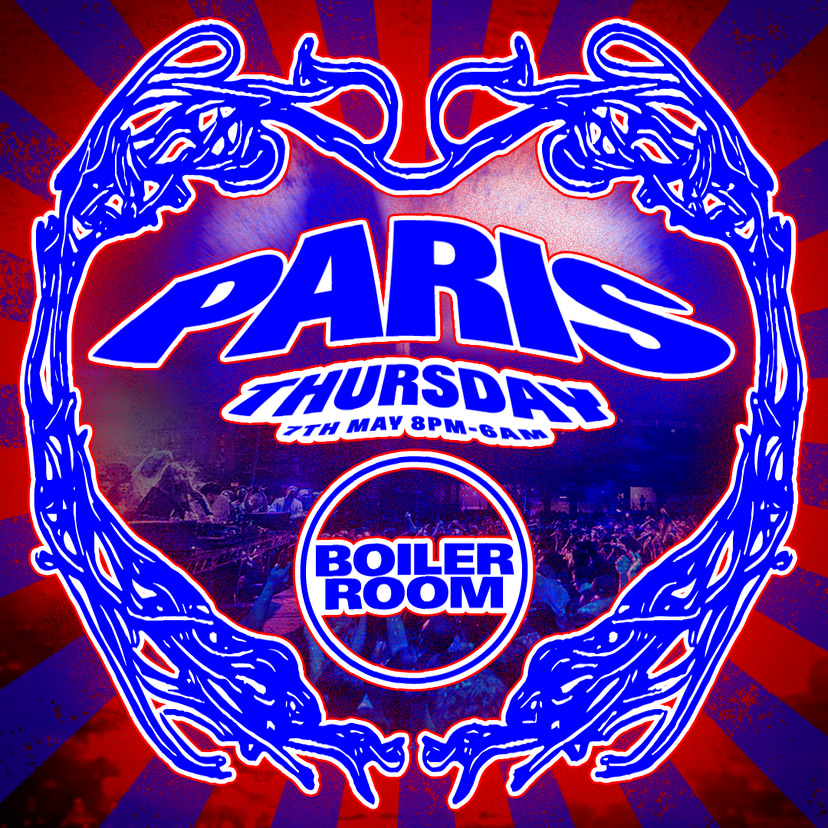

“It’s the Movida Madrileña but with reggaeton and trap,” says Ms Nina (pictured above) who has joined Boiler Room and Ballantine’s for a roundtable discussion along with Bea Pelea, CHICA Gang and Valle Eléctrico in Madrid. Only a few years ago, the sounds that characterise this movement were absent from the Madrileño club circuit. Instead, big venues offered up homogeneous nights of EDM, and thus brought together a homogeneous group of people. Those who grew tired of the lack of choice responded by launching their own DIY projects. “Suddenly we have this scene, this music, which we have made the conscious choice to consume on the internet, unlike everything else which is merely fed to us via TV and radio”, says Rocío, a DJ and member of the collective CHICA Gang.

Valle Eléctrico (Yeray, Tito and Diego) came together in 2012 to curate eclectic nights that brought experimental, lesser-known musicians to Madrid. Their most recent party at El Sol was no exception, beginning with a Cyberdog-meets-K-pop-meets-Spanish trap live show (Luna Ki) before plunging into gabber (Yegua). CHICA Gang emerged two years ago. Fed up of seeing all-male line-ups dominating the scene, DJs Rocío, Albal and Flaca began to host parties which championed those who had previously been shut out. “The way we all understand nightlife, the way we manage it, the way we understand this music... that’s our unifying factor,” says Tito, who handles booking and marketing for Valle Eléctrico. “That, and the emergence of these different communities who don’t shut themselves off from each other,” he adds.

"We don’t have resources because we’re not taken seriously.”

Defiant of the neoliberal mantra that life is a competition, what sets this scene apart is how much those who form a part of it support each other. Nearly 400 miles away in Barcelona, Bea Pelea (who is set to DJ tonight with CHICA Gang) hosts a monthly reggaeton and Latin music party called La Cangri. “It’s great being able to champion smaller artists who aren’t supported. Those who aren’t well-known have to combine making music with working a crappy job. It’s hard. You don’t have time and you don’t have money because the crappy job pays really bad.” La Cangri takes place in Apolo, which used to be a Mecca for the city’s Indie scene. “The venue has never really championed this type of music, which makes it more of a challenge,” adds Bea, who became a one-to-watch after collaborating on a track in 2016 with Ms Nina and La Zowi (who Flaca calls “the Queen of Spain”). Last year she dropped her debut mixtape,_ Reggaeton Romántico Vol _1.

Spain’s homegrown talent is charged with the potential to match, if not surpass, the success that Latin American exports are experiencing right now in the United States. Bad Bunny and J Balvin are currently two of the biggest names in the business. Balvin has collaborated on tracks with Spain’s own Rosalía, who made her mark fusing flamenco with current beats. Her second solo album, “El Mal Querer”, bagged itself a billboard right in the middle of New York’s Times Square and was ranked as the sixth best album of the year by Pitchfork. But her success story is exceptional, and when the artists brought together by the Boiler Room x Ballantine’s True Music project reflect on why they think that is, they talk of the cultural snobbery and classism that plagues Spain.

While Rosalía studied for years at the ESMUC – one of the best music schools in Spain – these artists are self- taught and most of their recordings are done at home. Despite their success, they still face prejudice and are held back by a lack of resources and financial backing.

“The people working in Spain’s institutions don’t get it,” says Rocío. “There’s this belief that academic, technical skill is what makes music worthy of recognition,” adds Yeray, art director and digital manager of Valle Eléctrico. “It’s absurd. This goes way beyond singing “well” or singing “badly”. It’s something else entirely,” he concludes. “More than a case of young people not being understood, it’s a case of these genres not being understood. They’re not considered to represent a rich language. They haven’t come from someone who’s been musically trained; no music school is going to give them the time of day...” says Tito. “We have nowhere to go to sing, nowhere to go and record, nowhere to go and practise. We don’t have resources because we’re not taken seriously,” says Flaca, a DJ and member of CHICA Gang. “We’re considered misfits, freaks.”

“Suddenly we have this scene, this music, which we have made the conscious choice to consume on the internet."

Without financial backing, making a living from their creative projects is next to impossible. Many can’t give up their day jobs, and those who have find themselves caught up in a daily battle. Over the last two days, Ms Nina has gone from DJing in a club until 4am, to shooting a documentary in the morning, then recording a track in the afternoon, playing an arena in the evening, and then participating in today’s round table the following morning. Tomorrow she flies to Argentina to perform and one can only hope that she will be able to sleep on the plane.

“I was working in a kitchen, and one day I said to myself, ‘This is not for me, I’m going to go and be Ms Nina’. But being an artist, being a musician, doing what we do, it’s difficult,” says Ms Nina. “I’m no millionaire,” she repeats. For promoters, the deals they have with the venues are in no way lucrative. For them, having access to spaces where more established artists and newcomers could come together to host events, practice, record, shoot, meet, teach, learn or collaborate, would make a huge difference.

“Basically you do it because you want to do it, not because you make money doing it. Doing this is working for free,” says Yeray. “At the end of the day, it’s not about wanting to be rich, it’s about wanting to be able to get by doing what you love, from the music that you are making. In Spain, it’s not so easy,” says Tito, who by day works as a science teacher. While a more conservative Spain is still choosing not to engage with this movida, or more accurately, is failing to understand what it’s really about, the artists and the community are all in agreement: this movement will go down in the country’s cultural history books, and as Yeray puts it, “it seems absurd to not make the most of what’s happening.”

Written by Eloise Edgington

Photography courtesy of Daniela Muttini