Breaking Down the Most Extreme BPMs in Dance Music

What happens when the BPM crosses 1000?

In 1993 mainstream producer Moby released the track “Thousand”. As the title suggests, it was one of the first recorded songs to reach past 1,000 beats per minute, registering at approximately 1,015BPM at its peak. The vigorous tune was later recognised by Guinness World Records for its extreme tempo. “Thousand” has more recently been recast for contemporary ears; techno producer Perc created his own edit in 2014 which was used to close his Boiler Room set that same year. While users in the comment sections of happyhardcore.com have declared this extreme BPM range the least listenable music on the internet, officially, it goes by the name extratone. AKA the world’s fastest genre, and the high-point of a BPM arms-race that’s been building in dance music since the mid-’90s.

Most commercial billboard singles clock in between 118-122 BPM, whereas typical hardcore and gabber tracks sit between the 150 and 200 BPM range. This makes them at least manageable for a dancefloor. From here, however, genres like Breakcore and terrorcore (characterized by a maximum BPM of 300) or speedcore (300 plus), generate a sonic assault quite unlike any other strain of dance music. When the BPM hits the thousands it becomes extratone. The point at which, to many, it no longer resembles music. “Past 1000BPM, the sounds become frequencies,” notes Federico Chiari, a hardcore researcher based in Milan. “Humans are capable of discerning these sounds on a speculative level, but not on a listening level.”

Chiari has spent the past decade piecing together the history of niche hardcore styles and their respective scenes worldwide. As hardcore has enjoyed its recent revival, Chiari feels many of these subgenres have been misrepresented. “The revival is taking the mainstream hardcore of the ‘90s and focusing on the dress code, more than the music,” Chiari laments. “Gabbers now are much more interested in the clothing,” he goes on to explain. “People are bringing back the stylistic stereotypes, but what was really interesting from this time is missing [in the revival].”

While the hardcore and gabber revival has given rise to more palatable crews like Casual Gabberz and the Drömfakulteten collective, more extreme sounds go overlooked and under-represented. Today, the niche nature of these scenes often means subgenres band together in order to showcase their individual sounds. Collectives running parties that platform these very particular sounds often begin the night with hardcore techno, before easing crowds into harder and faster styles as the night progresses. Persuading bookers to put on a night where their speakers might be damaged due to the extreme output of sound is a challenge in of itself.

Still though, hidden away in the dark online corners of forums and outdated blogs are enthusiasts campaigning to keep the legacy of hardest hardcore sounds alive. So, what are the most extreme BPM sounds in dance music?

Hardcore Techno:

Distorted bass lines fuse with washed-out leads to create the heavy rhythmic patterns that define hardcore techno, a subgenre of hardcore that often samples and warps well-known vocals from classic horror films. Frankfurt-born producer and Planet Core Productions (PCP) co-founder Marc Acardipane is labelled as the pioneer of hardcore techno and was instrumental in its formative years, often releasing tracks upwards of 160BPM.

Many Dutch artists claim The Leathernecks track “At War (Remix),” a 225BPM 1993 production from Acardipane was what soon inspired the speedcore movement in 1995. By the following year, Acardipane's music was exceedingly popular in the Netherlands, with many Dutch gabber artists finding inspiration for their own versions of hardcore in his previous productions. Acardipane remains heavily associated with both the history and future of gabber.

Underground Hardcore & Gabber:

The European rave scene began to split in 1992, the techno, house, trance and hardcore scenes separating out into respective communities. Around this time a scene emerged in Rotterdam, ravers pushing hardcore techno beyond 160BPM, utilising the iconic Hoover Sound of the Roland Alpha Juno synths to create breakneck tracks. Rotterdam Records founder and Dutch DJ Paul Elstak is regarded as the central innovator behind the gabber wave that swept outwards from the Netherlands in 1992.

At this point of increasing genre elitism, producers like Euromasters released unbelievably fast hardcore tracks in an effort to provoke house music purists. This strain of hardcore was initially much darker before the commercialisation of the Dutch scene in the late ‘90s, when much larger audiences began listening to mainstream hardcore and the scene mutated into happy hardcore.

Breakcore & Terrorcore:

At the end of the ‘90s, artists from the now-Berlin-based label Praxis such as Noize Creator were fed up with the constant speed increase of speedcore —we’ll come to that— so dropped their sound to a genre now called breakcore. Breakcore, which usually peaked around 300BPM was about speed, but with a focus on sensation and rhythmical elements rather than concentrating purely on the BPM range. Many breakcore artists were politically motivated and didn’t see rave music as a form of entertainment or hedonism, rather viewing it as a way to be provocative. This was championed by the Praxis — the group also behind Datacide, the magazine for Noise and Politics.

Sitting in a similar BPM range, but with a more irreverent, horror-inspired aesthetic, is terrorcore. The sound is similarly high-octane but perhaps attracts more attention for its fantastical, dark look. For example, Dutch artist Noisekick [pictured below] wears a mask similar to an orc straight out of Tolkien’s Middle-earth. The terrorcore producer’s sound resembles the post-internet uptempo pop side of hardcore and over the last twenty years, he’s showcased this remarkable sound at the Defqon.1, Thunderdome and Dominator festivals.

Speedcore:

Speedcore became its own genre in 1995, as the Dutch hardcore scene swayed to a poppier, commercial focus. Hardcore advocates and ravers were in search of faster more aggressive sounds that encompassed the anarchy that had developed during the early punk and death metal days. Speedcore producers combined hammering 909 drums and screeching vocals to create tracks that pushed sonic thresholds to their very limit.

The now-defunct Newcastle label Bloody Fist Records were the speedcore originators of the mid-’90s and the reason Australian producer Passenger Of Shit began pursuing harder styles in 1999, progressing from his former noise and industrial days into something a little more extreme. Although he boldly titles tracks “I Eat Shit” and “Puddle of Piss”, Passenger Of Shit doesn’t take himself or making music so seriously. “I don't really ritualise anything with Passenger Of Shit,” he says. “I use profanities and swearing to take it to another level in order to get that shock value I feel matches the sound. It was always done for a laugh. It’s a bit more poetic now, while I’m naming tracks after faecal matter there are still underlying themes.”

The Japanese speedcore scene is now one of the largest in the world, although “J-Core” producers release almost exclusively on CD, which can make getting a hold of their music difficult. The J-Core scene sways towards dancecore and mashcore — incorporating cheesy mash-ups of cult classics layered with the inseparable and iconic speedcore kick drum patterns.

Extratone:

German label Influence Recordings released Influid’s “The Destroyer (1.2million BPM mix)” in 1994, on which the artist increases the beat until it disappears into a continuous sound, as the capabilities of the human ear reach their absolute limit. Then, the beat returns as the BPM slows down. “There’s this interesting moment of the beat and rhythm disappearing into pure frequency and going beyond the 20,000Hz threshold of the human ear,” Chiari reckons. “It’s a very dark track.” These defining elements are what coined the term extratone: the extreme speed morphs the beats into a tone rather than a rhythm. The spaces between the beats are too minute for the brain to register.

Extratone developed during the internet era and through contemporary labels like the UK’s Slime City Records. It’s the sound hardcore devotees label as the ultimate extreme underground sound – a race for speed and velocity within music. The term extratone was born in speedcore forums online, born from people pumping out experiments to upload and share with the same goal as the first pioneers of the speedcore scene: to shock and annoy genre-purists by creating the hardest sound that they could.

Riccardo Balli is the only artist to ever release extratone on vinyl. “I consider extratone more subversive when it’s classed as dance music,” Balli declares. “When people try to tell me it’s noise I tell them they’re simply wrong”. His affinity with hardcore began at a London squat party put on by Praxis back in 1995. That night Balli contemplated the philosophy of speed within the context of sound and how it could move further, defying tonality as it stretched into more extreme BPM ranges. “I was born within hardcore music and I felt like I always needed to push the sound further, to shock people,” he remarks. “Extratone for me was that cultural shock.”

Sonic Belligeranza founder DJ Balli released Tweet It!, a collaborative LP with Ralph Brown in 2012. The pseudo-scientific record presents 14 tracks, each with a length of 1:40, and all with a BPM of 1,400. For the two artists, the record represents the sound of Twitter and how we approach new sounds in an age of constant noise. “The infection that is social media is spreading, and curiosity for weird music is a byproduct of that,” Balli adds. “Social media is about exploitation; we are contributing freely to a show and unaware that we are doing so. I feel as though we can utilise this to remove the constraints of the underground and spread new musically-driven concepts to a larger audience that are actively searching for the sounds of the isolated minorities.”

Written by Claire Mouchemore

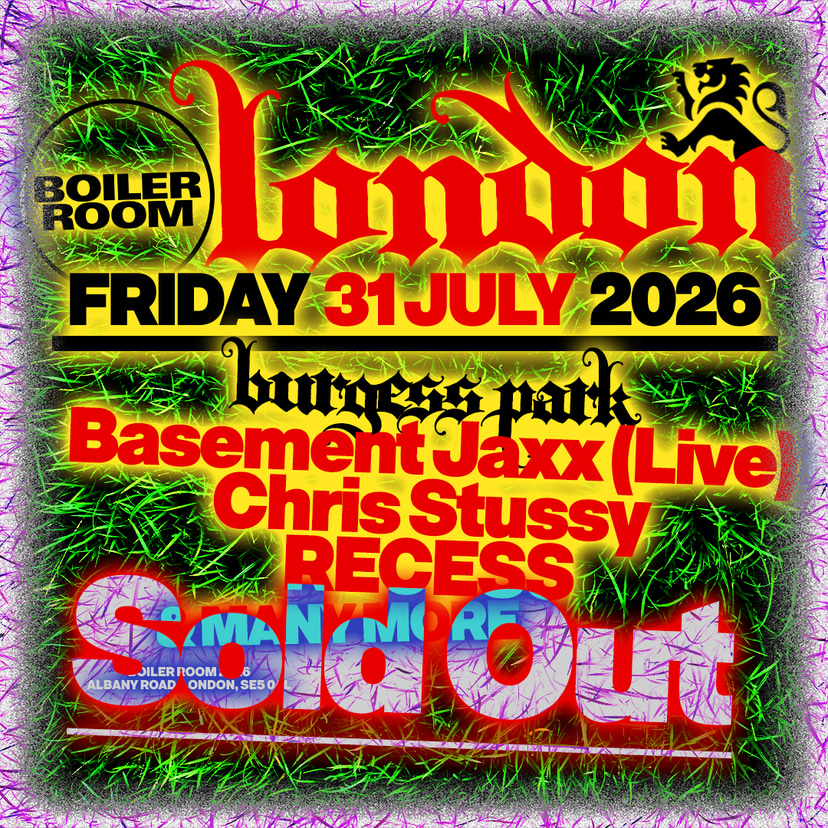

A part of Hard Dance, a series brought to you by Boiler Room exploring the hard and fast fringes of club culture. Find out more here.