Global East: A Rave New World

A myriad of progressive parties and festivals across Eastern Europe & Central Asia is giving a new generation an outlet to deal with their ex-Communist past and open windows into exciting new futures.

In recent years, a rave movement spreading across Eastern Europe and Central Asia started making headlines internationally, not only in music magazines and online platforms but also the major cultural media and global news. We’ve seen unsanctioned protest raves taking over the streets of the Georgian capital Tbilisi, whilst underground events like Kyiv’s Cxema or Polish festival Unsound have become worldwide phenomenons. Rave culture in post-communist countries offered something special: raw and authentic, it blossomed in former factories and disused swimming pools, consolidated local creative communities — and seemed to have a higher purpose than just simple entertainment.

For a new generation in Eastern Europe, Central Asia and the Caucasus, partying has become a way to express political views and find new opportunities. This current wave of rave in the East has grown out of the disorderly ‘90s, a decade marked by social and economic crisis, which has taught new generations to make the best of challenging circumstances. At the same time, organisers of movements in Uzbekistan, Georgia, Armenia or Lithuania might still have trouble explaining their experience to people of older generations who lived in the Soviet Union, be it their parents or their countries’ authorities. But where the latter can only see chaos and self-indulgence, the new generation has found freedom of expression and a key to global connection with their peers worldwide.

People from all over the world travel to Ukraine, Armenia or Uzbekistan to experience electronic music. But what is the broader meaning for the region and its future?

Political notions of East and West are still prevalent in contemporary culture, but they are much more about history rather than geography. The concept of the “Former East” emerged in the aftermath of the Cold War in 1989 - widely critiqued, it’s used intermittently with “Global East”, “New East” or “Former West.” In the global imagination, East usually includes Eastern and Central Europe, Central Asia and the Balkans. Sometimes, it encompasses only 15 post-Soviet states, sometimes also countries which had their own communist regimes, like Poland, Serbia or Hungary. It’s obvious no picture painted in such geographically broad strokes would be 100% accurate, and each of the countries has its own particularities in terms of landscape, history, mentality and contemporary politics.

One of the overarching similarities, however, is the fact that during the Soviet-era, nightlife and electronic music were not recognised as part of mainstream culture meaning their history only dates back to the DIY experiments of the ‘90s, such as Moscow’s notorious Gagarin Party. Named after the Soviet space hero, Gagarin Party took part among derelict satellites and rocket engines mounted on plinths at the space pavilion of the All-Russia Exhibition Center. But when we talk about Eastern European rave culture today, the focus isn’t just on the emergence of club infrastructure and the rise of underground scenes but about local identity in an increasingly globalised world. On one level, they are just dark spaces full of sweaty people - but on another, it’s a huge part of contemporary culture and a crucial tool of self-expression for the younger generation.

One of 2018’s most enduring images took place in May at Rustaveli Avenue in Tbilisi as thousands occupied the steps of the former Georgian parliament. It has since become a symbol of the rave’s political significance in the region. The protest was triggered by the brutal police raids at Bassiani and Café Gallery, key destinations for Tbilisi’s thriving techno scene. But the story was about something much bigger than techno: the new generation stood up for their freedoms and life choices. “Bassiani is a safe temple for an open minded, fast growing, progressive group of young people who will not be silenced or frightened by the system”, Bassiani resident Dj Gigi Jikia, aka HVL, commented at the time.

Bassiani images courtesy of Robert Sieg

Bassiani images courtesy of Robert Sieg

A year on, Tbilsi’s clubbing community continues to grow against a challenging political backdrop. “In the last few years, the political climate has hardened with right-wing and orthodox conservative groups appearing more often in the public domain,” says Tamuna Axander, founder of the techno club Khidi. “This particularly affects the local LGBTQ+ community. Our clubs provide safe spaces for people of different sexual orientations and ages to express themselves freely without judgment.”

The clubs also offer opportunities for raising awareness, social mobilisation and the exchange of experiences. For example, Khidi’s queer party series, KiKi, is not only a club night but also a platform for education and information concerning Georgia’s LBGTQ+ community. Axander admits that last year’s protests consolidated the club community in fighting for common causes.

Political conservatism and opposition to the rave movement can be found in many countries in the Global East, but this new culture has become enormously important. In Russia, similarly to Georgia, the new wave of queer parties and clubs, like Popoff Kitchen or Grahn’, are crucial for emerging LGBTQ+ youth. In Hungary, the home-grown electronic music scene is under constant threat of gentrification and a trend towards increasingly limiting regulations that are far more harmful to the grass-roots local scenes than they are to commercial, ‘international’ venues aimed at tourists. This July, Lithuania’s capital Vilnius saw a rave riot of its own: over five thousand people came out to protest frequent police raids and harsh drug laws, triggered by police storming the recently opened Platforma.

"Our clubs provide safe spaces for people of different sexual orientations and ages to express themselves freely without judgment.""

The overall struggle is not about individual events, but changing the perception of nightlife and ownership of public space. During the Soviet era, urban, public space was the domain of the communist party, reserved for military parades and celebratory, state-led demonstrations. In the ‘90s and early 2000s these spaces became the arena for the rise of capitalism - shopping centres and newly built apartment blocks sprouting uncontrollably in vacant areas. Today, the next generation is trying to reclaim public spaces which, they feel, have never really been public. Parties in this context assert the simple fact that human rights and freedoms should be above both economic and state power.

At the same time, alternative nightlife in the global East is not just about pushing progressive political agendas. The reclamation of dead space and DIY attitudes provides for experimentation, and is allowing young people to develop new opportunities for themselves. Kyiv is a good example: in the last few years the city has developed its own identifiably Ukranian club culture, supported by a thriving music scene. There’s a whole new generation for whom rave is an important part of their life and something that they can feel ownership of and participate in. Cxema is one of the initiatives which set the process in motion, founded by Slava Lepsheev in 2014 as a response to the nightlife vacuum created by the revolution.

Starting as an event for no more than a couple of hundred people, Cxema now takes place at Kyiv’s Tetra Pak factory or at the pavilions of Dovzhenko film studios, both with capacities of up to five thousand people. With meticulous attention to music curation and set and lighting design, the party has broken out of Kyiv, gaining international recognition, even getting invited to showcase what Cxema’s all about at Berghain last month. In terms of music, Cxema prioritises Ukrainian talent over big international names: Potreba, Konakov, Voin Oruwu, Nastya Muravyova and Tofu DJ are among the regular artists.

Cxema images courtesy of Vic Bakin

Cxema images courtesy of Vic Bakin

Closer is another big gravitating point of the Kyiv scene, growing into a cultural hub with galleries, shops, bars, showrooms, and a radio station. The team has expanded their music curation to large-scale festivals like Strichka and Brave! Factory. The third edition of the latter happened this August at Kyivmetrostroy factory and encompassed electronic music, art and cutting-edge set design. “For most people, Brave! is a conscious choice of expanding their cultural horizons, not just another festival,” says Alisa Mullen, who works in communications for Closer and Brave! Factory.

Alisa points out over half of the acts at Brave!, Strichka and Closer are always Ukrainian. This focus on home-grown talent is increasingly of interest to locals and visitors alike. “In recent years, I see more commercial brands interested in our communities and paying attention to this culture. This means there’s more support, including financial resources, so you can do what you love on an even bigger scale.”

Belarus capital Minsk is another example of outstanding grass-roots development. Still under the radar internationally as a rave destination, Minsk has a large and diverse local scene. Pasha Dankov started his Mechta parties in 2016. They’ve since become a benchmark of techno events in the city. He admits throwing parties in Minsk can be challenging: there is a lack of stable venues and very little sponsorship support for events. Most of the local audience can’t really afford to go out every weekend, drug laws are harsh and the LGBTQ+ community experience such extreme intolerance that there can be real risks to getting out and dancing.

But the drawbacks are offset by the enthusiastic community: “The spirit of the events is the best thing: it’s like every single person is conscious of their small but still important contribution to cultural development.” Dankov feels Minsk is on the cusp of a creative explosion, “when we’re able to overcome the information isolation and national complexes.”

Another highlight of the Minsk scene is Bassota, a night running for five years that has provided a local focus for clubbers seeking out bassier sounds. Their 40+ events to date have spanned UK garage, 2step, grime, dubstep, juke, footwork and ghettohouse — genres that are traditionally less prevalent in Eastern Europe. Bassota initially started as a series of video podcasts about the local scene, evolving into regular nights and a music label. “Belarus is really on the rise with electronic music at the moment, with lots of unique musicians, DJs and promoters across different genres and styles,” Bassota crew member Alex Aslamin tells me, whilst lamenting “the only thing we’re missing is decent music media.”

Urvakan Festival

Urvakan Festival

Across the region, rave culture is certainly one of the prominent forces shaping the cultural life of big cities, but by no means is it limited to just a club context. Independent festivals create a deeper conversation about history, locality and the way music relates to time and place. Urvakan in Armenia launched this May, bringing almost 100 artists and DJs to perform at unique venues, including a ruined railway station, a river dam, and a stage deep within woodland. As part of the experience, visitors had to walk through a 460-metre-long tunnel to reach the festival’s main venue: a Soviet-era fairground.

The organisers are aiming to finesse the details of next year’s edition rather than upscale, stating one of their main goals is “to keep it weird”. Context is crucial for Urvakan organisers. "There were loads of questions left unanswered. What’s the role of music in rethinking the national identity? How can one deal with haunting memories?" The festival is a tool of communication, they state, adding "we just want to create an unusual space where things can safely clash into each other – genres, languages, different races, genders and nations.”

Uzbekistan's Stihia festival is even further off the beaten track, taking place on the shores of what was once the Aral Sea, now a desert strewn with the skeletons of abandoned ships. The sea dried out following Soviet experiments in the ‘60s to divert rivers for growing cotton — an enormous ecological disasters starved of global attention by Soviet secrecy. Music might have started her journey, but helping the region ecologically and economically is one of the main aims for Stihia’s founder Otabek Suleimanov.

Stihia Festival

The festival location is 1200 km from the Uzbek capital, Tashkent, and transporting 15 tonnes of equipment by trucks is no joke, but this year the festival is going to be even bigger, run over two days and will include a mini-forum on ecology and a forestation programme. “This is the first attempt to raise awareness about the death of the Aral Sea”, Suleimanov says. “No one has ever done this before. There were many articles, many conferences, but they were all boring, never ever done in a way as we do - creative, beautiful, and very loud!”

Overall, these electronic music communities in countries of former-communist influence might still not be recognised as part of the mainstream culture. But it’s important for each nation, and the region as a whole, not to be underestimated. Rave is creating economic opportunities and a cultural dialogue which are incredibly inclusive — from entrepreneurs to clubber kids, to the LGBTQ+ and creative communities, and whoever enjoys a bit of techno on the weekend.

It’s also an investment in the future: teaching the Global East’s Gen Z about ownership of public space, the importance of local talent and the power of grassroots initiatives. Most importantly, it educates about the beauty of the collective experience - something which might have been entirely discredited by the fall of the Soviet Union some 30 years ago. They never had a chance to believe in the power of collective experience in the same way their parents and grandparents did, but today rave culture offers a way of coming together which is above the historical trauma of the Soviet era, or commercial capitalism that replaced it.

Today, Eastern European rave culture is often portrayed as a product of Western influence, but it’s something much bigger, more independent and powerful. For a new generation in the Global East, it’s a tool for creating the future they want for themselves and their communities, while throwing a few unforgettable parties along the way.

Written by Anastasiia Fedorova

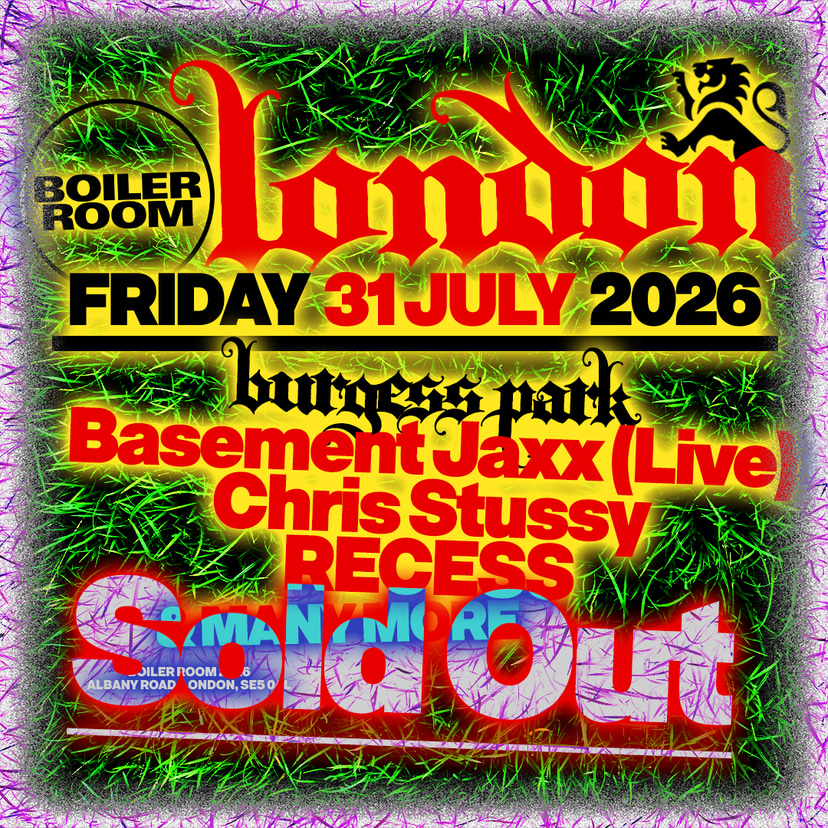

A part of Global East, a Boiler Room series spotlighting new generations turning to Rave Culture to shape the future of their communities.