Nyege Nyege: an uncontrollable urge to dance

Erin Cobby meets the organisers and artists involved in Nyege Nyege, the East-African collective introducing new fusions and genres to Uganda and beyond.

“Nyege Nyege!” erupts from all corners of Nyege Nyege festival, it seems to happen randomly, filling the rare lull between sets that run from Thursday evening until the early hours of Monday morning. Posed as a call and response, it puts the similar “Dave, Alan!” chant common throughout English festivals to shame. People don’t just shout it, they emit it – eyes shining brightly, they throw their heads back, until everyone around them echoes the same words – it’s not a chant, it’s a rallying cry.

The meaning of 'Nyege Nyege' was one of the first questions I posed to Derek G. Debru, one of the collective’s organisers, when we met up back in Kampala a few months later to discuss their festival, label and everything else they do. Back in Jinja, the festival’s Nile-side location, I’d asked a few patrons the meaning of the word and got a variety of answers. “Sex” was one that came up a lot, as did “testicles”, something whispered to me by a very timid, blushing man. When I relayed this to Derek he laughed, clarifying that testicles were “negge, negge” in Luganda.

He explained the name was born when one of his Muganda friends turned to him at a party and tried to convey what he was feeling but couldn’t find the words in English. It turns out what he was trying to explain was the Ugandan concept of “Nyege Nyege”, the uncontrollable urge to dance. This seems a perfect name as when I ask Derek to describe the overarching sound of Nyege Nyege. “There's definitely an emphasis on booty shaking,” he tells me. “You know people love to dance here, like it’s a natural interaction with music.”

However, the confusion is understandable, with Uganda alone being host to 43 living languages. In Swahili, Nyege Nyege means ‘horny, horny’, a different kind of uncontrollable urge, something which hasn’t helped detract from Uganda’s Minister of Ethics, Simon Lokodo, attempting to have the festival banned for being a hub for hidden homosexuals.

Once inside, Nyege Nyege festival feels miles away from the divisive politics it has found itself embroiled in. The space - half beach, half jungle - is generous enough to wander through, yet the seven intimate stages allow the festival to retain the smaller party vibe Nyege Nyege has grown from. This potentiality of individual experience is made more impressive as MTN sponsorship, Uganda’s largest telecom company, made 2018 the biggest festival yet, with 8,500 attendees.

This sponsorship is representative of the fine line Derek and the other organisers have to tread when contemplating festival growth. While corporate sponsorship would spell sell-out to many western festival goers, Derek suggests there is little “anti-corporate culture” within Uganda. Sponsorship denotes legitimacy, rather than the opposite. The challenge is “more in terms of managing the popularity and making sure the vibe and culture of the festival doesn't get diluted,” Derek states.

This threat seems to come from two angles. As a festival founded by Europeans, they have to be hypersensitive to avoid pushing musical colonialism and instead encourage natural growth. This seems to be working given the large Ugandan following and network Nyege Nyege has fostered from the outset. Derek states he wants to avoid having Nyege Nyege go the same way some other festivals based in Africa, with a programme entirely for tourists which doesn’t engage with host communities.

PEOPLE LOVE TO DANCE HERE, IT’S A NATURAL INTERACTION WITH MUSIC

They also face the problem of ensuring the festival programming retains the fringe local genres that were instrumental in their decision to launch the Nyege Nyege collective. Many Ugandan patrons going for the experience would be just as happy listening to more mainstream music. Derek states this divide was even more apparent last year, citing that during Juliana Huxtable’s set, about half the crowd was white. He then went to check out the other stages, like Bell Jams and Wild Bay, the MTN stage, which was largely, if not completely, Ugandan. “So that just triggers questions”, he states.

It seems the challenge Nyege Nyege organisers face now, having created a festival big enough to have something for everybody, is encouraging these people to mix. “From the beginning we wanted to create something that really showcases all the sounds that are on the continent and also give people an opportunity here to listen to something else.” Derek tells me. If this task seems gargantuan, Nyege Nyege are definitely capable of achieving it.

Their associated label, Nyege Nyege Tapes, is already known on a global level as a platform which encourages disparate people, and types of music, to mix. One group which embodies this philosophy is Nilhiloxica, who merge Bugandan drumming with techno to create a powerful grimey sound which manages to embody both an ancient culture and a basement in Leeds.

The best example of this however is the Nyege villa, a residency for international artists, which I was invited to check out during my stay. The place is massive, with producers and musicians hidden behind each door. The space offers opportunities for musicians to learn and live, encouraging those from different African nations and the wider European electronic scene to engage with and teach each other. This year’s residency invitees is a good barometer of attempts to facilitate further trans-continental collaboration prior to the festival. Indonesian outfit Gabber Modus Operandi, Japanese breakcore producer DJ Scotch Egg, Swiss-Congolese Planet Mu and Purple Tape Pedigree associate Bonaventure, Istanbul-based Elvin Brandih, and Kinshasa powerband Fulu Miziki among them.

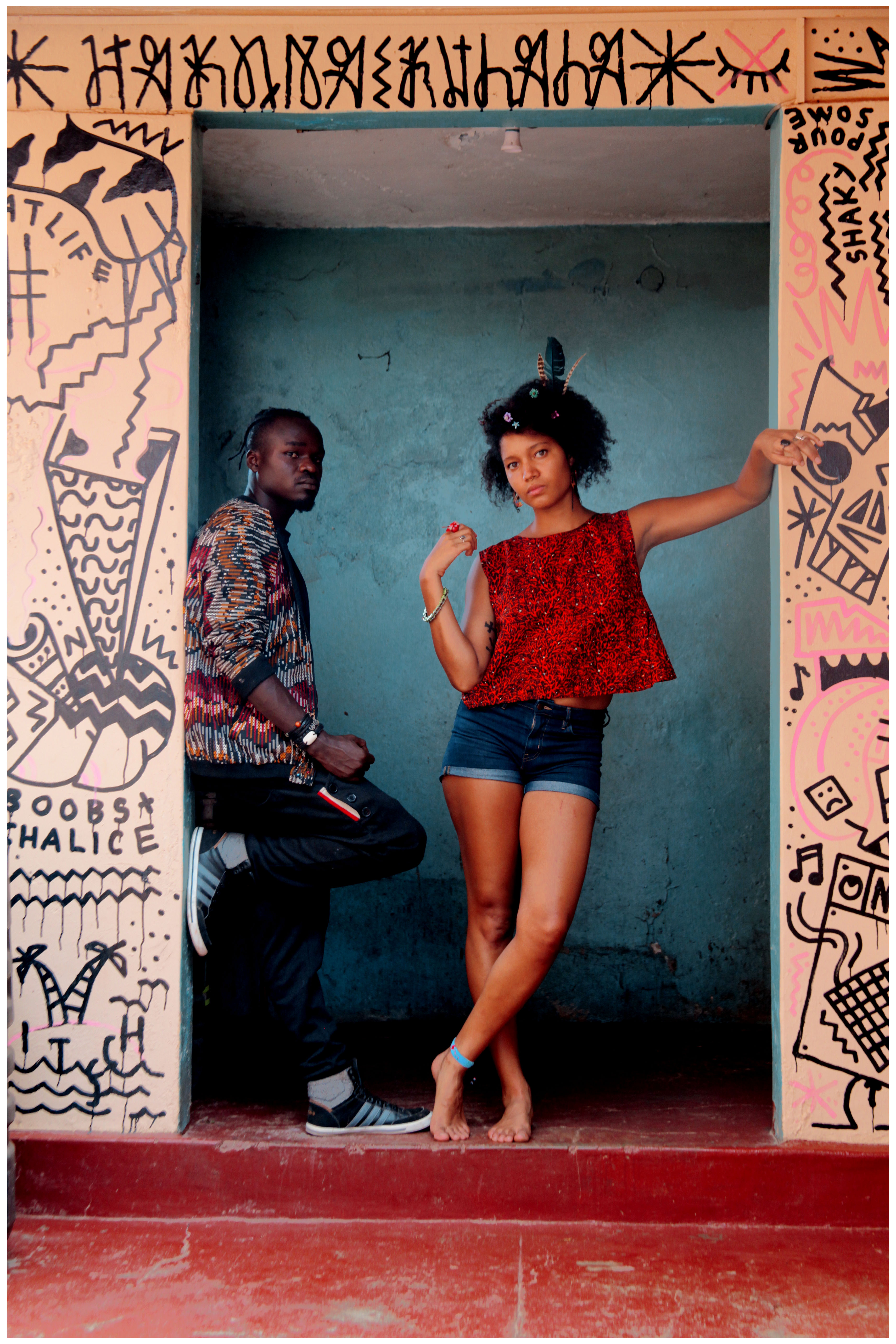

A group to have already benefitted from this unifying atmosphere is Poko Poko, a conscious pan-African queer pop duo hailing from Canada and DR Congo respectively. Feminist messages delivered by Pauline’s soulful voice, paired with infectious party beats and interludes of Rey’s French bars, makes it easy to see why they’ve managed to appeal to the Ugandan club scene. I witnessed this first-hand when Poko Poko performed at The Factory, a club in Kampala's industrial district, the crowd going mad during their set.

The duo met through Nyege Nyege and have been supported by the organisation throughout their tour in Rwanda. They will soon be releasing new tracks on Hakuna Kulala, a sub-division of Nyege Nyege Tapes devoted to a club-orientated digital sound. Rey has been with Nyege from the start, founding Hakuna Kulala after he created a new genre of music by fusing Soukous, traditional Congolese pop music, with electronic music to create what he calls “Congotekno”.

Rey was given a book on Ableton back in 2016, self-learning the production software with some help from producers who came through the Nyege villa. He picked their brains until he started his own production classes in 2018. What makes him happiest? “Ladies making beats.” Growing up in Kampala, Rey wanted to make mainstream music, so spent a lot of time in that scene. What he saw propelled him to seek work in other genres; a huge pool of talented female musicians in Kampala would need to trade sexual favours as well as cash to get access to production studios.

It gives him massive amounts of satisfaction to see female producers working with male musicians. That’s his aim now, alongside following his own musical endeavours, to teach as many women as possible in East Africa to produce. “And in all of Africa”, he adds smiling, “if I can find them to teach.”

Rey’s drive to open up the music scene across Africa is one that’s quite difficult to achieve. Derek informs me this is since African musicians face huge challenges when trying to tour outside their own countries. More so if they play more experimental music, as they are even less likely to get booked. Having the Nyege Nyege brand behind an artist gives them international credibility and having a base like the villa enables easier travel and collaboration which in turn encourages more trans-African merging. Unfortunately, this is not always enough, exemplified by Nyege Nyege Tapes artists Duke and MCZO being refused entry to the U.S. earlier this year after travelling to New York to perform at a Red Bull Music Festival.

Two people to benefit from the Nyege framework very recently are Chris Mec and Chris Man, rapper and producer, the latter who had only been in Kampala for three weeks at the time of interview. They came together as a duo back in Goma, DRC and shortly afterwards came to join the Nyege crew in Kampala. Despite both hailing from Congo they state that their main influencers are DJ Khaled and David Guetta, not Congolese musicians.

Chris Mec tells me that this is because it is hard to make a name for yourself as a musician in Congo, “because in Congo art is not promoted.” However, since the two arrived in Kampala, Chris Man tells me, they’ve been trying to "mix universal music with culture music”. Nyege first contacted Chris Mec after he won a music competition in Kinshasa, DR Congo. Since his arrival he has featured on tracks with some of Nyege’s most prominent artists; Poko Poko’s Rey, Slikback and Stylo. He states all these projects opened him up to new music and has even influenced him to mix genres of his own. “I used to do trap music, but then I found out that everyone is doing trap music”, he tells me.

Chris Mec created Afrokolic, a blend of classic Congolese music and trap after meeting the musician Infrapa, an exponent of Kalindula rap; itself a combination of Congolese and Zambian styles. Chris Mec reveals Infrapa opened him up to the idea of recording with live musicians instead of just using playback, and therefore Afrokolic is the type of music that can incorporate a wide range of instruments. Watching Chris Mec perform is mesmerising, with an energy that seems inexhaustible as he leaps around the stage, spitting impossibly fast over heavily influenced trap beats. For Chris Mec, the teachers at Nyege are exposing him to a new type of producing, something he calls “speed beat”, a style which, concurrent with the whole Nyege ethos, will “make people want to dance.”

Apart from exposing these two musicians to new genres, both men also tell me that they have since been schooled on how to use effective self-promotion and how to capitalise by creating a business strategy. Furthermore, being attached to the label has enabled further success, Chris Mec states that during his tour, which covered parts of DR Congo, Burundi and Kenya, he already had a following. “I can go somewhere as a Nyege artist and people expect something”. He finishes by saying that Nyege taught him “how to go from the impossible to the possible”.

With the Nyege name growing in notoriety year on year - they were recently awarded a prize for tourism from the Ugandan government - it seems this September the festival is set to top even last year in terms of numbers. Acting as a champion for indigenous genres, and enabling further trans-African collaborations, Nyege Nyege will be bringing more people than ever that irresistible urge to dance in September, at the source of the Nile.

Written by Erin Cobby, a freelance journalist who likes to focus on East Africa. She is currently the Managing Editor for shado - a magazine dedicated to raising the voices of those at the front of social and political change.

A part of Contemporary Scenes, a BR series uncovering underground collectives, artists and subcultures from across the world.