Understanding the Visual Language of Gabber

Before the fashion houses took hold, what was the original gabber look?

Gabber was never just about the music. When it first exploded in the Netherlands of the 1990s, an entire youth culture was borne. One with its own set of social codes and visual signifiers. Identifying as a gabber was both empowering and dangerous. Over the ensuing decades, gabber culture has faced damning stigmas and prejudice, surviving spectacle and ridicule often down to the diehard devotion of its fans. As the saying goes: Gabber ben je niet voor even, Gabber ben je voor heel je leven! (“You're not Gabber for a moment, you're Gabber for life!”)

Yet, in the years that followed its heady explosion, these signifiers have been sampled and then swallowed by fashion and popular culture. Starting with Raf Simons, who soundtracked a Rotterdam-inspired collection with gabber during a Paris runway show in 2000, all the way through to Vetements and Christian Dior more recently, shaved scalps and windbreakers have been a source of limitless inspiration for designers. And it’s not just fashion. Photography, graphic design and even typography have drawn on the visual extremes of gabber cultures.

So where did it begin? Who—and what—shaped the original look? Here are eight visual references that defined an era.

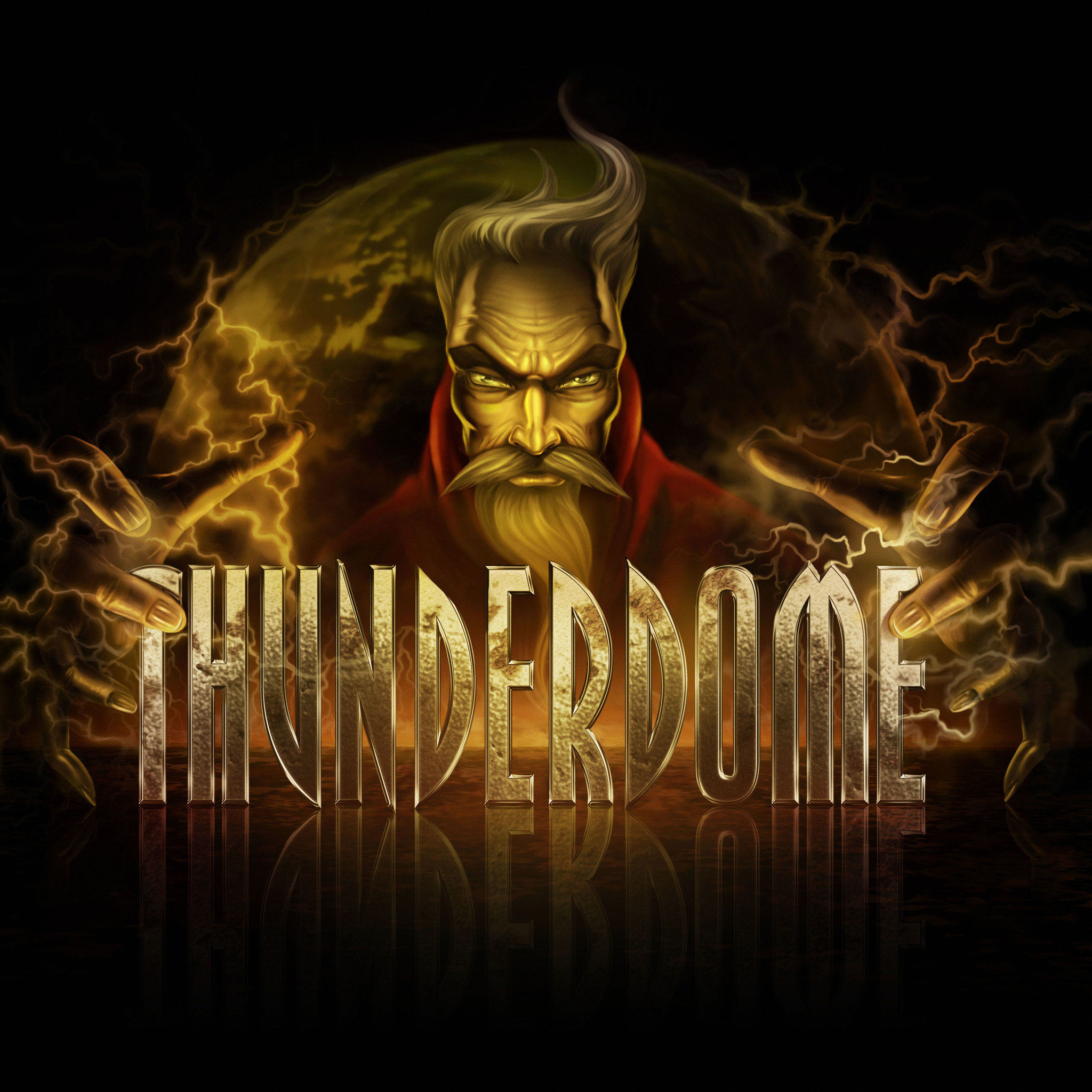

The Wizard

The Wizard is the ultimate gabber icon. With his balled up fists, he has come to represent what gabber is all about: extreme, different, part of a tribe. It's why thousands of people across the globe have a Wizard tattoo. For a decade Amsterdam-based tattooist Hollywood Mark has been branding diehards with the Wizard, an image that began as a graffiti mural by the artist MODE 2, but was made famous by ID&T as the logo for Thunderdome.

Hollywood Mark wasn't really into hardcore at first, he's a punk rocker, but after tattooing hundreds of fans (and DJs) in his studio and at Thunderdome events he's become part of the tribe too. "After I did my first event I thought, this place is crazy, but the people I tattooed were so nice,” he explains. “They're really loyal people, loyal fans, dedicated to what they believe in. It's made me get into hardcore and be more mindful about judging people."

Sweat It

The sportswear look (tracksuits and trainers) was adopted in the '90s for practical purposes: to dance (and sweat) more freely in the rave. Brightly coloured Australians from the Italian tennis brand L’Alpina were the the most exclusive (and expensive) tracksuits at the time, and were something of a gabber status symbol. Though rarer these days, wearing them is still a symbolic act of devotion. "Today the old-school Australians are mostly worn by a dedicated younger crowd who are into the underground early hardcore sound," says Bobby Jacques, a Rotterdam first generation gabber and clothing collector who still wears his with pride.

The Big Window

More support. More comfort. More attitude. The Nike Air BW—or "Big Window"—came out just ahead of the gabber explosion and was the ultimate raving shoe. Overshadowed by other more popular Nike Air releases, like the Air Max 1 and 97, the BW had more of a cult following, worn by subcultures across the globe from R&B stars in the US and hip-hop communities in France, to grime crews in the UK. In the Netherlands, BW's were worn by gabbers and like the music have experienced a comeback in recent years. Some things never die.

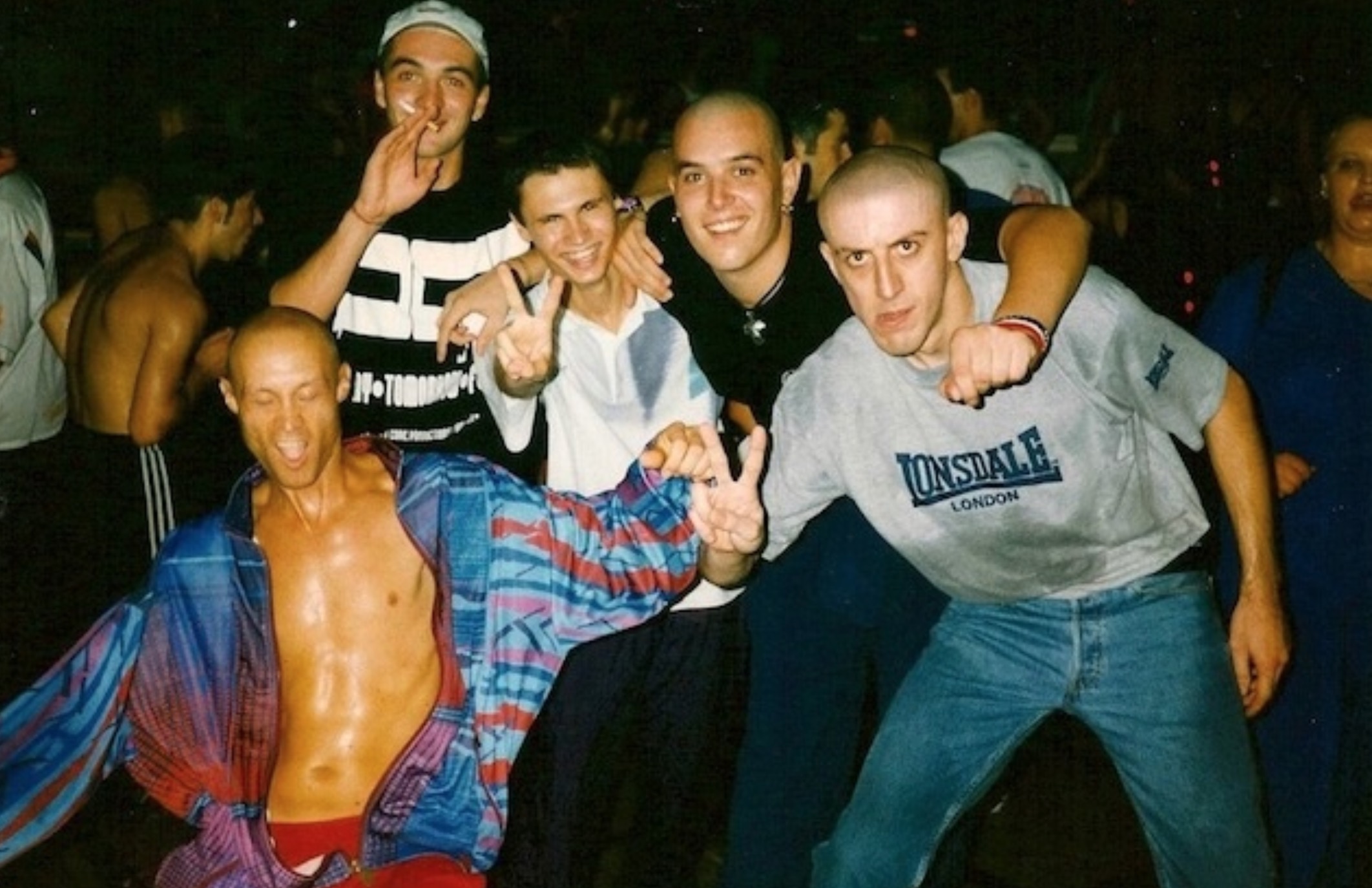

Going Bald

Australians and Nikes were expensive, but anyone with a pair of clippers could shave their head. The various gabber hairstyles for boys (the baldy, the island, the blockhead, the banana peel) and the undercut and ponytail for girls was the easiest way to prove your hardcore credentials. The practical implications of being literally cooler in the rave with such a haircut have been exaggerated according to Boris Postma, a second generation gabber, visual artist and researcher of gabber culture. "It was about showing your feathers, showing what scene you belonged to and looking tough.”

The Lonsdale Youth

When gabber reemerged as hardcore in the millennium it came with a new uniform: polo tees and button-down shirts worn under sweaters or jackets with rolled up jeans and army boots. Lonsdale was one of the most popular brands at the time, and it was also the most notorious. "My parents hated the original gabber tracksuit style," explains Postma. “For me, this new, neat style of clothing was a way of showing my love for hardcore on the streets and still get away with it at home. Of course, all of that changed when Lonsdale-wearing youth became a national outrage."

The media quickly sensationalised the link between wearing Lonsdale and right-wing extremism, going as far to dub it the “Lonsdale Youth” crisis. “Media would focus on the loud, racist minority which got regular people to fear gabbers even more,” adds Postma. “If you were a gabber, everybody would have an opinion about you and it probably wasn’t a positive one.”

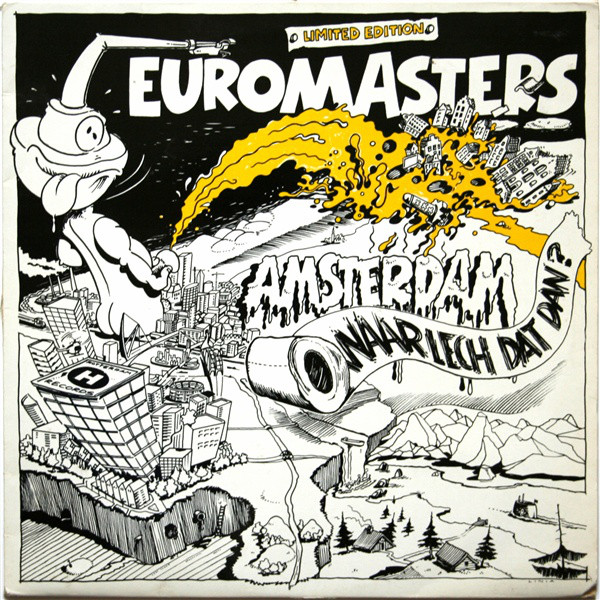

Rotterdam Techno = Hard Hard Hard

The pummelling sound of Rotterdam gabber had a cheeky face in the form of cartoonist Kees Linia's iconic Euromast character––a caricatured illustration of the city's most renowned landmark. Often depicted with his tongue lolling out in crude satirical scenes, he epitomised the adolescent rebellion of the gabber youth. One of the most iconic Rotterdam gabber records of all time, Euromasters' debut record Waar Lech Dat Dan? ("Amsterdam, Where's That?”), depicts the character pissing on a map of Amsterdam, referencing the inter-city rivalry that bled into the gabber scene from fierce football feuds between Ajax (Amsterdam) and Feyenoord (Rotterdam) supporters.

“Your Worst Nightmares”

Horror and hardcore have been bedfellows since the beginning. From large scale Hellraiser raves in Amsterdam (with Pinhead as MC) and the Freddy Krueger-indebted Nightmare events in Rotterdam, to the clowns, snakes, possessed dolls and other characters of the night that ID&T illustrator Victor Feenstra created for Thunderdome, gabber music has always lent itself to foreboding artwork. The novels of Stephen King and cult films from Wes Craven, Clive Barker, Donald Mancini and others during the '80s and early '90s were endless sources of inspiration.

"I don’t like to use the word 'monster’ much myself. I prefer creatures who enter your worst nightmares," says Victor Feenstra, whose haunting visuals have recently been compiled in the book, Eye on the Underworld. He created some of the most distinctive airbrushed artworks of the time. "It had to be ‘rough, tough and striking. Hard and scary and dark as the music itself."

Planet Phuture

Gabber was made in the Netherlands, but its musical blueprints were formed in Germany via Marc Acardipane and the Frankfurt crew Planet Core Productions (PCP). Written in 1989, Acardipane’s "We Have Arrived" (as Mescalinum United) is regarded by most as the first hardcore techno track. Its title refers to a new alien sound––the sound of the “phuture”––and came with a tripped out alien graphic to match, hand drawn by PCP member Darius Gawlik.

During a time of lurid colour schemes, cartoons and evil villains, the sleek sci fi minimalism of the PCP logo and the black and white typographic sleeves of Acardipane Records, which came later, were as singular as the music itself. These were all created by Paul Nicholson, the designer best known as the creator of the ubiquitous Aphex Twin logo.

Written by Holly Dicker

A part of Hard Dance, a Boiler Room series exploring the hard and fast fringes of club culture.