–

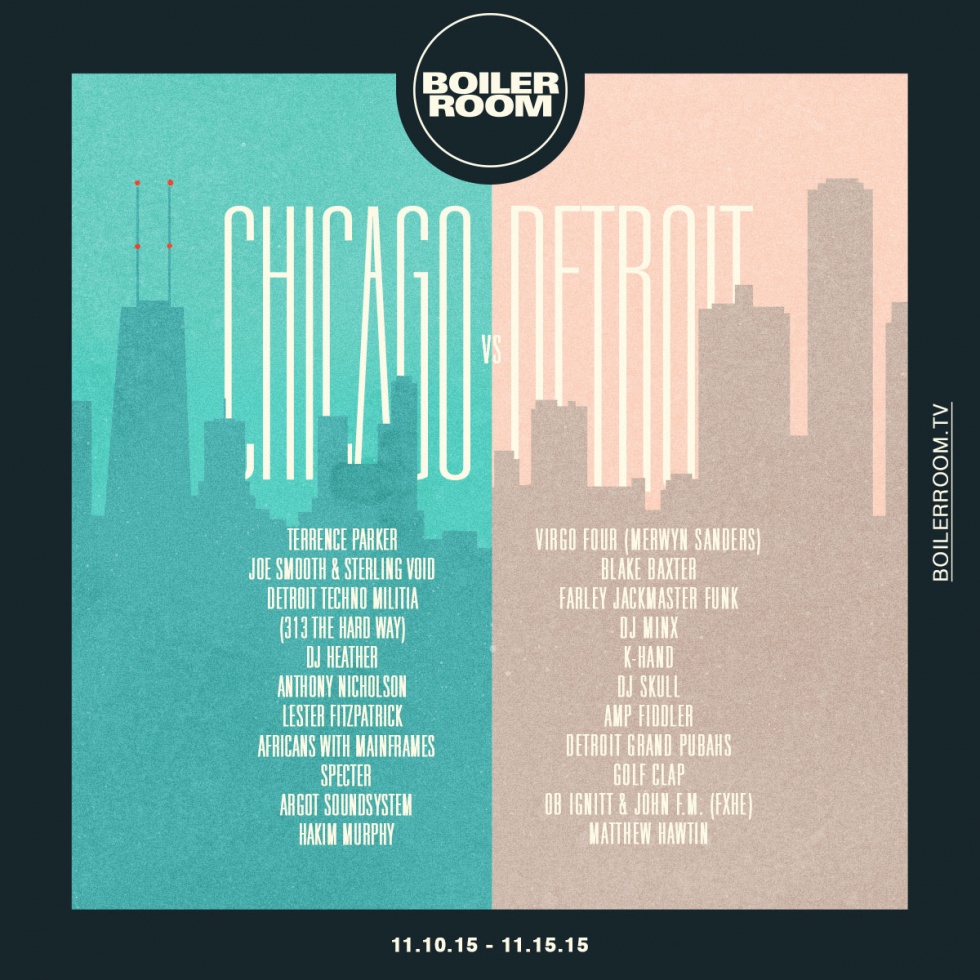

This year, we undertook a mammoth weeklong Chicago vs Detroit trip: four shows in six days across two cities, with 20+ artists down for the ride. You can find out more and watch archives for each show – #1: Chicago by night; #2: Chicago by day; #3: Detroit by day; & #4: Detroit by night.

Before we left for to the Midwest to road trip down the I-94, it made sense for Boiler Room to delve a little deeper into the curiously under-documented connection between these two crucially important cities. Throughout the 1990s, they fed into one another in key ways: the tribes intermingled, the talent pooled, the music merged; and, nestled in snug lofts and airy warehouses alike, house and techno both burrowed underground to avoid commercial co-opting.

All this allowed both scenes to diversify – and thrive. Read on.

–

The story is well versed, but in case you need a refresher – Chicago house music was created by innovative DJs and producers melding disco, Italo and beat tracks, mainly at black gay dance clubs such as the Warehouse and the Power Plant and at teen parties like the Muzic Box and the Playground. The sound spread quickly to Europe, spawning Britain’s ‘Second Summer of Love’ in 1988-9, and Ibiza’s party scene in its wake. By the time the rave movement made it back to the U.S., many Chicago kids assumed it was a European invention. Chicago’s original house scene, hurt by city crack-downs on juice bars and the growing popularity of hip-hop, needed to evolve to escape extinction.

Salvation came in the form of DIY, mostly illegal pop-up parties in places like lofts, warehouses, and even the occasional outdoor space. Out of this fertile environment came a second wave of Chicago DJs and producers, who moved the music forward, exchanging ideas with Detroit, and proving that house was more than just a passing fad. Legendary record labels – including Prescription, Balance, Cajual and Relief – were born.

One record that’s emblematic of this second wave is the Symbols & Instruments‘ Mood EP on Kevin Saunderson’s Detroit label, KMS. This 1989 release was penned by three up-and-coming Chicago artists: Chris Nazuka, Derrick Carter, and Mark Farina, who would come to share a loft known as Red Nail, the letters that spelled out their phone number. Listening to the record, one definitely hears the Detroit influence.

Carter was a music buyer at Importes Etc., a fundamentally important Chicago record store. After it closed, he went to work alongside other at Gramaphone [which played host to our daytime Celebration of Chicago session this March – Ed.] Chris Nazuka began DJing in college up in Madison, Wisconsin. He and Mark Farina had been friends since eighth grade, sharing an interest in New Wave and industrial music, and playing in bands before discovering house. Farina introduced Nazuka to Carter, who had already recorded for KMS as 24-7-365. “We all got along, started hanging out, became friends,” Nazuka recalls. “That’s how we did our first record together.”

The trio travelled to Detroit three or four times to lay down the Mood. During that period, Kevin Saunderson, Derrick May, and Juan Atkins were all working in the same building. “To us, those guys were our idols,” says Nazuka. “It was our first time meeting Derrick May, and he was totally down to earth and really, really cool – just giving us good advice, and playing us stuff that wasn’t released. We were freaking out, because we were just heads at that time.”

They went to the Music Institute in Detroit as well. “That was one of the coolest clubs I’d ever been to,” Nazuka enthuses. “It was really raw, and it was huge. They had a massive sound system – speakers piled on top of each other fifteen feet in the air. I remember “French Kiss” [by Lil’ Louis & The World] had just first come out, and Derrick May was playing that, just beating it!”

For the most part, Nazuka, Carter, and Farina worked in Kevin Saunderson’s studio, but “Tear Drops of Yesterday” from the record’s B-side was recorded in Juan Atkins’ space. “That was my first record out ever,” Nazuka continues. “We were still nineteen years old, and we were all excited about it. We did it in ’89, but I don’t think it came out until ’90. It wasn’t that big here, but overseas it did pretty well;” it was a fittingly commonplace caveat at the time.

When the move into the 1,000-square foot Red Nail loft finally came in 1991, a whole new freedom opened up. “It was empty space, and we had to build our own drywalls. We built four rooms. Derrick had his turntables in his room, Mark had his turntables in his room, and then I had mine in my room, but we also set up the studio in my room,” Nazuka recalls. “It was total analog – we had 909s and 808s, stacked.” The trio recorded mixes to sell at record stores and made tracks to play at loft parties. Derrick Carter was spinning Tuesday nights at a small club in Chicago’s Boystown called Foxy’s. “We would make stuff at our loft, and he could play it that night to see how people liked it,” Nazuka explains. “It was just a great way to get instant feedback about how a track does or how it sounds on the dance floor.”

“You didn’t think of it as ‘this is techno and then this is house’ – it was all under this big umbrella of dance music.” – Chris Nazuka

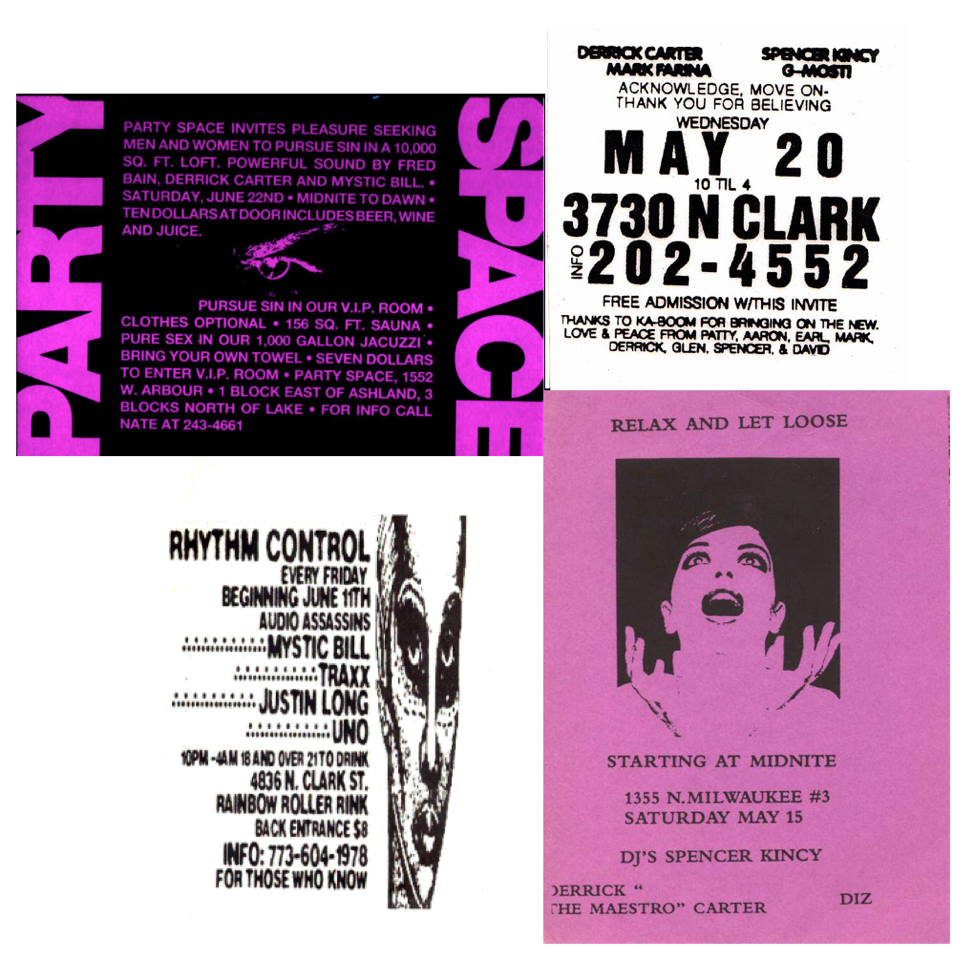

All of these DJs were participants in a vibrant loft party scene which blossomed as old-school clubs like the Muzic Box and Medusa’s started vanishing. Many of these parties were along Milwaukee Avenue in spaces known just by their street numbers, the most famous being 1355. “You wouldn’t even know the name of the event, just there was a party at 1355,” DJ Davey Dave Mason explains. The sound systems were cobbled together, as were the lights, but the atmosphere was intense.

The first wave of integral loft party promoters included Seth Love, a Medusa’s regular, Dwayne Washington (Diz), and Andrew Substance. “The loft scene was really cool, because you got people that weren’t really into going to clubs,” says Mystic Bill Torres, who moved from Florida in 1988 and started throwing his own parties in 1991. “There were the track heads – the kids, the jackers and stuff. They would go and start these jack pits. It was like being at a punk show, but it was a house party.”

Muzic Box devotee David Gandy and Spencer Kincy (later known as Gemini) threw a series of parties in their own apartment starting in 1988. Gandy and Kincy listened to a handful of mix tapes to choose DJs, saving Farina and Carter’s for last. “I think we just sat there and looked at each other for about fifteen minutes after we finished listening to the tape, because it was something totally different, something totally unique,” Gandy recalls. They were playing hard, fast records on Detroit labels like Transmat and KMS alongside Chicago artists like Fingers Inc., using an Alesis Quadraverb for effects. “Back then,” Nazkua says, “you didn’t think of it as ‘this is techno and then this is house’ – it was all under this big umbrella of dance music.”

At one of the so-called Substance ‘rent parties’, Derrick Carter played an unreleased Derrick May track off tape. “Things went into overload,” DJ Scott Song recalls. “There were so many people jumping up and down and hedonistically dancing that a lot of the hosts were running around and trying to calm down some people in fear of losing the dance floor.” Under some 250 dancers, the loft’s wooden floor often bounced up and down dramatically. The impact of Detroit was becoming increasingly harder to avoid.

Looking back, it seemed like everyone was getting involved – indeed, a separate scene was hopping in tandem on Chicago’s South Side. Gene Farris began DJing at the Powerhouse with Ron Carroll and DJ Rush around 1992. “The crowd back then was a majority black crowd, and most of the music being played back then was either disco or edits and a lot of tracks from Trax Records. People like myself, DJ Rush, Boo Williams and Glenn Underground, we were all making our own tracks and just playing them out at the party.”

DJ Frique (Terry Allen) introduced Farris to the North Side loft scene, and soon Frique and Farris were throwing their own parties at 1471 Milwaukee Ave. as part of Erotic World. The parties consisted of nitrous oxide tanks, illegal alcohol, and house music. Frique and Farris also spun at 1355 Milwaukee Ave., alongside DJs like Traxx. Farris’ list of key loft scene records, often getting their first major break or a vital second wind in that environment, reads like a run-down of bona fide classics.

A pivotal promoter in Chicago’s loft, warehouse, and club scene was Wade Randolph Hampton, a DJ who moved from Texas to Chicago in 1988. Captivated by the underground – or, indeed, above ground – scene, Hampton began throwing his own parties almost immediately. “They were called Wade’s World and they would start at either midnight or seven in the morning. Those would be in places that I had strong connections with the owners, that understood our vibe. Sometimes it was Old Town restaurants with a bar upstairs or a speakeasy downstairs or at my loft,” he explains.

The opening of the Shelter nightclub in 1990 poured fuel on the fire, legitimatising a scene that had otherwise been content to sit in the grey area of legality. “The minute Shelter really kicks into high gear, that changes everything,” says Hampton, who heard Mark Farina spinning “Strange Brew” by Cream there, and began throwing his own parties at the spot. His Outlaw parties, the afterhours destination for those in the know left a club party, then descended on a random place with a sound system in a pickup truck, drew in New York club kids, including Project X magazine’s Julie Jewels, Mike Alig and Keoki.

One evening, the Outlaw party was raided by police after only twenty minutes. Some of the participants went to Hampton’s loft, where they decided to break into a hotel they thought Geraldo Rivera had visited for his live show, The Mystery of Al Capone’s Vaults. “We peeled back the wood on the first floor, and about sixty people pile onto the second floor where there’s no windows left,” Hampton recalls. The party quickly spiralled out of control. NYC’s club enfant terrible Ernie Glam, on roller skates, threw a bottle of vodka out a front window, hitting a passing police car.

The entire group was arrested and, high on Ecstasy, proceeded to throw a fashion show in their holding cell.

“The ravers called them black boogers. That was the sign of a good party, back then.”

When commercial raves first began in the Midwest, they were a completely separate animal from the underground parties preceding them. “The music and the kids didn’t cross paths,” Davey Dave Mason explains. “The loft scene would be a little bit older crowd, and they were more black, Asian, Hispanic, urban. The rave scene was suburban white kids, college kids, and skater kids from the suburbs. The rave scene would have a lot of gabber and ragga, drum and bass, trance, and European influenced stuff like that.”

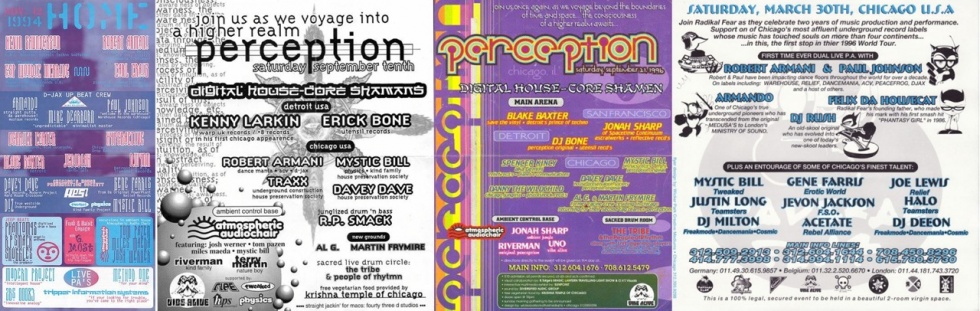

With House Preservation Society, founded in 1993, Davey Dave and Mystic Bill made it their mission to introduce ravers to Chicago house and Detroit techno, which they felt was being overlooked. “We wanted to teach the new raver kids about the history of house and techno, and that it all started here,” explains Mason. Their earliest events were held in huge warehouses all around the city. A few parties were even held in a basement where the legendary record label Trax Records was founded. “Larry Sherman gave us the keys to throw a party in the basement,” Mason recalls. “There was a couple of busts going on at the time, so we just gave out a voicemail: we said call this number and we’ll call you back with the directions.”

About 300 people showed up to the first event there, and the atmosphere was unique, to say the least. “You’re walking down, there’s holes in the ceiling and literally slime going down the walls, you’re stepping on gritty cement,” Mason describes. Since the building’s power had been disconnected, the crew had to haul in their own generators. After the party, everyone was blowing dust out of their noses. “The ravers called them black boogers. That was the sign of a good party, back then.”

In 1994, House Preservation Society began a series of parties called Home, which further reinforced the connection between Chicago and Detroit. Roller rinks, South Side malls, larger and larger spaces: we were pretty brave,” admits Torres; cocksure might be a better way to put it. The first Home included Detroit artists Kevin Saunderson, Carl Craig, Blake Baxter, and D–Wynn. Chicago artists included Armando, Mike Dearborn, Paul Johnson, and Robert Armani (all of whom had releases out on Detroit-affiliated label Djax), alongside the usual cast. “Close to 3500 people attended – including Cajmere and, for the very first time, Paul Johnson.

The mark left on a young Cajmere is an especially amusing case. Shocked by the sheer scale of the proceedings, he later paid tribute to those heady days in the epochal “Flash“. As Mason would have it, “some of these guys who grew up on the South Side knew Europe had a rave scene, but were otherwise oblivious. They walked in like: “This is going on here in the States?!'” Caj asked House Preservation Society to hold a Relief Records party in 1995 as part of their Vibe Alive series – the hair, goggles and full Green Velvet transformation.

As with all great parties, Chicago’s loft and rave scenes couldn’t last forever. The intermeshing of Chicago and Detroit’s sounds became increasingly more pronounced as the 90s went on: Chicago house got significantly harder and trackier; Detroit’s second wave took a good dollop of the depth and soulfulness from down the I-94. As the 2000s dawned, with the Midwest scene arguably past its dizzying peak, a string of city ordinances targeted property owners, promoters, and even performers participating in unlicensed parties, especially if drugs were found. The community clubbed together – producer Steve Poindexter even ran a security service for some of these parties and assisted in finding spaces – but the tide proved tough to turn back.

A rumor that one of then-Chicago Mayor Richard Daley’s family members had a bad experience with ecstasy made his crusade all the more personal. This, combined with the federal Illicit Drug Anti-Proliferation Act passed by the U.S. Congress in 2003 (which introduced fines of $250,000 or more for holding events where controlled substances are present) effectively shut the lid on Chicago rave culture. Luckily by then the city’s club scene was picking up again, but the dynamic was bound to be different.

Those loft and rave scenes were an important bridge between the pioneering parties of the 1980s and today’s underground scene, where Detroit and Chicago are both recognized for not just their contributions to dance music history, but a pervading Midwestern unity at large. It may not have been the initial aim, but in hindsight both city scenes benefited enormously from pooling talent and resources in that era, keeping the culture alive. That the attendees of these early events have grown into some of the most influential figures in the contemporary American dance scene, and many records from that time period remain classics, throws weight behind how, together, Chicago and Detroit are greater than the sum of their parts – even if it was something of a happy accident.

– Our mammoth Chicago vs Detroit trip has been archived in full. Four shows in six days across the two cities. Find out more HERE –