The similarities between video games and music are more obvious than you might think. Firstly, they’re enormous and enormously diverse entertainment industries. Think too in terms of experience: you can have deeply affecting moments of solitude and introspection; you can have moments of sheer communal joy; you can even half-ass your way through it while focusing on other stuff.

Even for those who don’t consider themselves core gamers or deep music heads, they leave significant imprints, and not just in terms of fond personal memories – it’s a shared cultural reference point for millions, after all. Twitch and Boiler Room have shared bonds, both being global hubs for online broadcasts and social interaction alike, which is why we’re creating a custom stream to bring their users the best of our world. Find out more here.

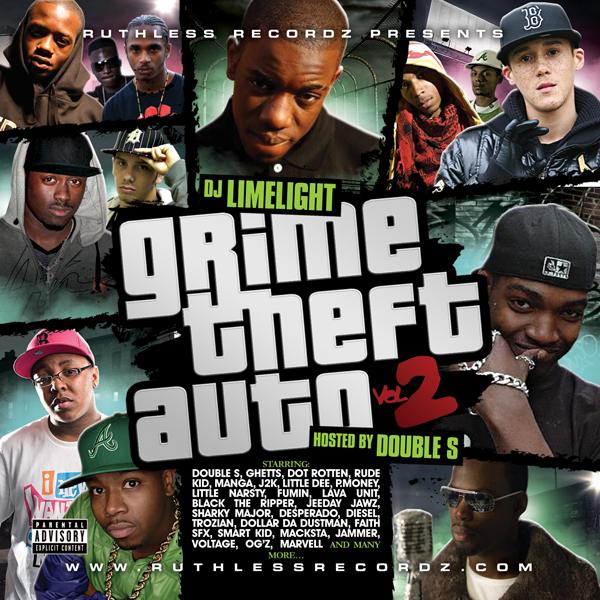

One genre in which the relationship between gaming and music is most blatant and important is grime. Read on to find out more about the ley lines intersecting, and how mutually beneficial it has proven in recent years.

—

For a whole generation, video games provided a constant backdrop to their childhood years. The late eighties and early nineties were progressive times, with grand leaps in innovation and a plentiful choice of technology across the board. That 15-20 year stretch remarkably changed the way we live; the first time that the games console was a typical, omnipresent feature within kids’ homes, more or less from the cradle.

So it’s no surprise that producers have regularly turned to their game cartridges as a source of inspiration. The discographies of Hudson Mohawke and Joker are obvious examples. Just a quick earful of “Digidesign” is enough of an indication of the many overt homages to the arcade. Something about that period of raw technological exhilaration fits hand in glove with the basic principles of electronic music so perfectly. An echo of its primitive analogue beginnings, perhaps.

Yet no one movement has arguably been as closely aligned with the control pad as grime. Born out of early 2000s London, grime embodied the inner city struggle of the working class. A raucous, saw-wave shaped middle finger to the establishment in a world where entertainment and luxuries were very much limited to video gaming and knock down ginger. From its instrumentals to its lyrical content, grime’s debt to the console can not be overstated.

“For our generation, Sega Megadrives or DOS games were current. And as youth, whatever you hear, you absorb – at that age, you’re a sponge.”

“I guess for our generation, Sega Megadrives or DOS games were current. And as youth, whatever you hear, you absorb – at that age, you’re a sponge,” says Dark0. Flying the instrumental grime flag high in his own productions, Dark0’s progressive take on the genre is loaded with manic rhythms and epic synth work, veering between gritty and euphoric – check his Sin EP on Lost Codes or psychedelic track “Amethyst” for a taster. He’s unmistakably a gamer at heart. “And it just so happens that so many soundtracks were melodic – people had a lot more scope to be mad crazy with melodies. Everyone who’s a gamer from this age group has an ear for melody.”

To understand why gaming is such a vital component of grime you have to skim back through its timeline. Most of the grime community – the original crop that includes Wiley, Jammer and Skepta – are between the ages of 25 and 45. The heyday of the Megadrive, MS DOS, early Nintendo consoles and Gameboy – the eight-to-32-bit chiptune consoles – fall slap bang in the middle of their childhood or adolescence.

“I remember when it was time to get the Megadrive and Street Fighter came out. Hearing the energy of that sound and the music within the game was different. When you heard M. Bison’s music, you knew it was intense and that that was the boss level,” adds East London producer Rude Kid. “The Mortal Kombat theme music would automatically just make me and my brother just fight. The tie between the gaming and music is nuts. I got a couple of samples from Mario including the coin sample, which I reversed.”

During its embryonic stages, grime was sonically some distance away from its 2015 counterpart. A time when the digital home production era was still in its infancy – awash with 256-colour screen Motorolas, shoddy Bluetooth exchanges and Snake 2 high score boasts. The tools of the music trade could be called primitive now, yes. When placed in comparison with DAW titans like Pro Tools, which were staples of professional studios and not the bog-standard home computer, of course they appear so. This was a digital landscape initially occupied by Mario Paint (which JME has used) and Music 2000 on the Playstation. Fundamentally, you were limited to the sound you could use in these games as a soundtracker. The melodies had to be very simple and striking. A single lead wave here, catchy drum patterns there, but all sounding very bit-crushed and techy.

Whether consciously or not, part of those producers’ aim was to recreate the garish but deceptively complex soundtracks of their favourite games. Infamous SFX snippets from polygonal paradises like Sonic The Hedgehog and Final Fantasy had some of the most relentlessly catchy compositions in pop culture at the time. Composers like Yasunori Mitsuda and Koji Kondo (and their OSTs) managed to incorporate amazing stories into their music, accompanying the peaks and troughs of the game. The hooks and melodies producers were exposed to would then become a big part of their lives and musical influence. They’d be immediate reference points just as much as hip-hop, garage and dancehall.

“I was renowned in my school for fucking people up at Tekken. Others on Street Fighter.”

These techniques could be deployed with more sophistication when Fruity Loops (later FL Studio) entered the fray. The pattern-based music sequencer made by Belgian company Image-Line made it possible to compose and record a song out of your Windows 98 PC, burn your riddim on to a rewritable CD, pass it to a DJ and hear it played on a pirate radio station that same day.

But its not just the game melodies and the nature of the hardware that had a profound effect. The types of games were instrumental, namely platformer epics and fighting games with their adrenaline-pumped SFX nabbed from anime and kung fu films. “I for example was renowned in my school for fucking people up at Tekken,” continues Dark0. “Others on Street Fighter. If you were from this era and from London you were most likely a video gamer on one of these platforms.” This admiration for the orientalist way of life helped give birth to sinogrime – a term used to describe the far east-reaching grime sound of the mid-2000s.

It also boils down to competition. When growing up, a lot of people in the UK and London especially are very localised in their mentality. “You want to be the best at something in your ends,” says DJ Logan Sama; “be the best baller, the best MC, biggest shotter or whatever – it’s very area orientated. It’s the same with gaming, that arcade or [games machines in] the chip shop mentality back in the day. If you’re the guy that can beat everyone in your local then you’re the guy.” Logan is not only one of grime’s most revered disciples, but another avid gamer. Sama rose to prominence through pioneering then-pirate radio station Rinse FM, before moving on to hold the only grime DJ position on commercial radio (via Kiss FM) for almost 10 years.

“For me as a person, I don’t have a lot of things I’m interested in but the ones I am I’m really passionate about. So when Street Fighter 4 came out in 2009, I got really into that and discovered the competitive scene, which was based around London. One of my friends would go down to the arcade because he played Tekken, and I never really liked Tekken. But when the new Street Fighter came out in the arcades, I went down to the arcades and just wanted to play and learn so I bought myself a stick. From there I became friends with all the top players in the UK.

“It’s very similar to the grime scene: really disorganised, full of really passionate people that didn’t have the infrastructure that the likes of Call Of Duty and FIFA and some of the big PC games like League Of Legends and Counter Strike.” Logan started running a weekly Street Fighter 4 tournament called Winner Stays On in the HMV Gamerbase in Trocadero, which quickly became the most popular event of its kind in the UK. Now he hosts weekly sessions at the CAPCOM offices who stream it out on Twitch — the world’s leading video platform and community for gamers.

Games have always been a competition. Grime godfather, Wiley, boasts about being a “27 big achiever, E2 weaver, had the first SEGA…” on “Crash Bandicoot Freestyle”. Winner stays on, victor keeps the pad. More than anything, the grime and gaming link is more about energy and excitement. Nothing beats that feeling of being at the boss stage after hours of playing, palms sweaty as ever.It’s the same energy that’s locked in tight when two MCs exchange the mic after 16 angsty bars.

Gaming and grime are both one of the same. Escapism, perhaps. But more than that, that same escapism feeds into real life and nourishes the thoughts of small, yet important communities of young people. Ignoring the intrinsic link between grime and games would be criminal.