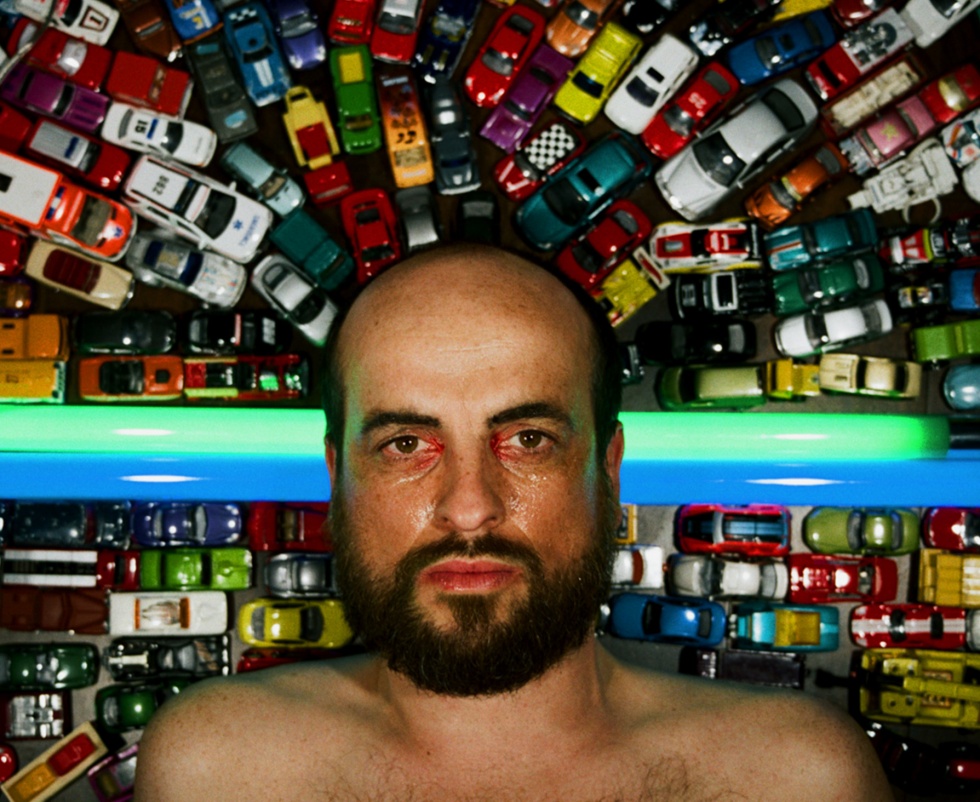

Matthew Herbert’s first album under the Herbert alias in almost a decade is, in a word, strange. So too is its creator: intensely, brilliantly so.

Herbert is the quintessential English eccentric, making some of the durable and enjoyable dance music of the past twenty-odd years, all while never remaining fixed in one place for too long. He’s soundtracked everything from UK springs to hypercapitalist wastelands, and sampled everything from laser eye surgeries to pig slaughter.

Following a run of lowkey house classics in the 90s-turn-00s, he took a number of sharp left turns in the shape of big band tours and educational deep-dives within the British Library for Boiler Room. What ‘conventional’ albums see release often come with self-imposed restrictions that border on the insane. Last year saw the return of a more conventional variation of Herbert with a clutch of killer EPs; although even the dancefloor-primed lead cuts on these were constructed with saucepans and spoons.

If anything, Herbert’s propensity to over-complicate and overthink every little thing marks him out as an almost tragicomic figure; simple just doesn’t come easy for the man. In conversation he mulls over his words, often repeating phrases multiple times to trim the fat and whittle down to a reduction he feels comfortable with.

Still, he spins a great yarn – somewhat in spite of himself. To mark a return to our BR screens, we let the idiosyncratic genius loose on all manner of topics: touching on The Shakes, his disorienting career arc, and the complex interactions between culture and geopolitics. Read on.

GABRIEL SZATAN: I’m curious to know if there’s a chronology of events that sparked a return to the Herbert alias.

MATTHEW HERBERT: I always think of making albums as asking a series of questions: you maybe start with a hundred questions; you answer a handful and carry the rest to the next record; then you find out you’ve got a few more of them. And so I often feel like a spider near an empty bath’s plughole, circling round and round before sometimes getting a bit of energy to pull out of that, before coming back into it. When I started, I thought the gravitational pull was innately toward dance music. But as I’ve got older I’ve realised that it’s much more to do with a fundamental question of why make music in the first place? Why not write a book? What can sounds do that a feature film can’t? So I’ve come at this series of questions from a different angle each time.

I did a Big Band album in 2008, which had about four hundred people and thousands of samples, and it took an awfully long time and large amount of money. So immediately the next record I made [One One] was all me, and functioned like the antithesis of the one before, if you like. I tied my hands together on the record prior to this by saying ‘one five second sample, and that’s it’. So after all these opera and theatre and art installations and radio programmes and a ton of other things – not all of which were that well received – I wanted to give myself a bit of a break. I wanted to remember who I was, and where I came from.

When you’re reverting to a more simplistic way of working, do you have to battle to suppress your own tendencies and proclivities?

In the writing process I was pulling up any old sound and just riding with it. I lent my Fender Rhodes to someone who never gave it back, and I can’t quite bring myself to buy another knowing that I already own one, so I wound up using a preset – yet I hate how Logic have sampled that soft synth. It’s really ugly. But by then it’s stuck, and nothing you can do can quite replace the quality. And so that’s what I find really hard: feeling like a fraud, knowing there’s a crap sound from early in the composition buried somewhere deep in there. It’s a bit like eating a ready meal when you know you’re perfectly capable and you’ve got delicious fresh produce in the fridge. It doesn’t feel like the best use of your possibilities.

“Suddenly anything and everything can be turned into materials…that feels like one of the greatest gifts musicians have ever been given.”

The new record leaps all over the map: some hark back to a more subdued 90s-turn-00s Herbert; then you have others with lavish arrangements, like the sprawling, organ-heavy 11m closer. One constant that stood out is a heightened emotional resonance, especially with the yearning vocals throughout. What specifically were you trying to convey?

Music seems to come with an “otherworldliness” quality to it: it conjures something out of nothing and exists nowhere, and so taps into the idea of something beyond the self. Within that there is an inherent melancholy, in the sense that if you were happy with the status quo, you wouldn’t need to express yourself. I reached a conclusion that the creative act tends not always to be borne of happiness. If I’m really content at home, I don’t feel the urge to rush to the studio, whereas if something’s up, it’s a way to iron out issues.

I’ve been quite tightly wound for the last few years, because I feel a responsibility knowing that suddenly anything and everything can be turned into materials for making music. You can use a toilet brush, or a volcano going off, or a drone bombing people in Pakistan, or roof tiles, or David Cameron resigning – that feels like one of the greatest gifts musicians have ever been given. It’s absurd! So I had a real philosophical debate with myself, placing a pressure to fight against my own instincts and instead make music that’s more generous. Something different happened last summer, where I rediscovered the need to write a record about something that makes me happy. One of the things that makes me happy is my family, and while I told myself it’s really naff to write about my children… that’s accidentally what I did.

I started writing on a personal level – “One Two Three” being about my son, who was three at the time – and then Israel started a war in Gaza. The number of children being killed was extraordinary, and it became impossible to stay happy in a way, writing about my children without acknowledging the hideous crimes perpetrated against children in Gaza or Syria; it became impossible to be engaged with the world and not feel incredible privilege. So the record started off with one impulse, and then very quickly morphed into another, which was about the present. It’s about what it’s like to be alive today, feeling joy and love at the good things around you, and horror and fear at the rest.

So even when setting out to do the opposite, you wound up with another album challenging listeners to take stock of their surroundings, and engage with a broader political situation.

[Laughs] Yep.

Were you using those Parts Six – Eight EPs as toe-dips to test the mood, with a raft of material in hand, or were they not meant to be a multi-stage rollout for the album?

No, I wasn’t even necessarily going to make a record. It was an opening of the curtains, I guess. It was a chance to do some tracks, and act upon a slight frustration of the waves dance music goes through at the moment: something really exciting happens and then fizzles out within three or four months.

Are you alluding to anything specifically?

Not in that particular instance. While I’m busy doing other things, I still DJ once or twice a month, and so remain very conscious of it all without staying atop every single release in the way that the younger generation do. I go and do my research a week before I DJ, to sort of catch up on the last month’s worth of music. You bring a few tracks in, move a few out, and notice how quickly little movements rise and fall. A big disappointment for me was dubstep: so exciting and mad and truly inventive, and for one of the first times I felt really left behind because of the different ways of using language and sounds and production techniques – and then it just sort of ate itself rather too quickly. Last year there was a great thing with house music using bigger basslines, and now even that seems played out.

“I learnt so much from Dance Mania and old Chicago records about how to marshall rhythm”

You’ve spoken before about the democratisation of access to production software leaving people with a ‘crisis of ideas,’ so have you come to enjoy these micro-cycles moving at extreme pace at all? It must feel like the blurred definition and massive buzz of insects constantly criss-crossing each other.

It’s an interesting thought; I don’t feel I have a very compelling answer. It’s a bit like playing with your kids: they’ll come up and stick a tractor in your face and say, “look it’s got blue wheels!”, and then they’ll come back thirty seconds later and go “look, an enormous carrot!”, or maybe, “a twig in the shape of an elbow!” It’s quite tiring, actually. The music is okay, but the hyperbole that goes round it is the thing; the number of acts that you see hyped, then never hear from again.

The other real problem that I have with it is the sound, which I think has got a lot worse technically. Compare some old records from the 90s, where the lack of compressors means there’s consequently a well-rounded punch, with all the frequencies coming at you at the same time. Now, there’s loads of compression everywhere, tracks are maxed within an inch of their life and the mid-range has collapsed a bit.

It presents real issues while DJing. The majority of music that I like, and that I make, tends to eschew straight drum machines for wooden spoons or saucepans, and what have you. A lot of detail is in the mid-range and so the absence of top and bottom end means that, even when playing these incredible sound-systems in Germany, all that stuff sounds crushed and weird. These big rigs are set up to play laptop music, and it’s very fatiguing to listen to. I find it harder to take some of see longevity in the new micro-stuff just because I don’t think it will age very well. But maybe in twenty years all music will sound that horrible. But of course it’s healthy that people are expressing themselves, and I think it’s fantastic that all sorts of people who would never have had an opportunity to make music are now getting that chance.

I simply can’t get away from listening to Dance Mania and old Chicago records, plus Nervous and Strictly Rhythm to an extent. For me, dance music is about rhythm, and I learnt so much from those labels about how to marshall rhythm, and how it works. DJ Premier, Mr Oizo, J Dilla: they all fit into this kind of music that I love the most, stuff that has this incredibly rich relationship with rhythm. Whatever sounds are there I can take, if there’s a core understanding of what it means to move, you know?

How did your recent return to live shows go? Was K15 a hand-picked support?

It was good! We had a really nice and supportive audience, which was maybe a surprise. There’s a lot of pressure to get that right – new costumes, new lights, new music, new material, new tricks, and what have you. I think we just about pulled it off! And yes, I was sent a list of potential support acts and I enjoyed the link of him DJing, so that was about it really. Again, it goes back to rhythm, and I dug the swing of it; it’s the one thing I miss in a lot of dance music.

Keeping that prick of excitement and expectation over where they’re going to go next is so important. Even if the DJ’s not going properly left, those little fluxes in the over-arching three hours of a set are much more fun to follow than the linear path of peaks and troughs, like someone walking up and down a miniature step of stairs.

That’s right. I remember seeing Richie Hawtin at Ministry of Sound in about 1993, hearing him play a load of Todd Terry stuff, and you can’t imagine him ever doing that now. It’s entirely different and really interesting to see quite how linear it’s become.

“By this point a lot of dance music should be made of watermelons and Ford Fiestas and the Liberal Democrats”

Well how about the Dance Tunnel show with Mr Wonderful [aka NTS founder Femi Adeyemi] last November? That’s a small environment so surely a lot of the pressure gets lifted. How do you approach a set like that, and what do you aim to achieve? I can’t imagine you can really get people thinking laterally about socioeconomics on a dancefloor at 2am.

DJing for me is always an exercise in managing other people’s disappointment. I’ve been doing it now a long time – over two hundred remixes and thirty albums and a lot of other stuff – and people develop very intimate relationships with the music that you’re not always privy to. People can get upset and quite cross if you play something that they don’t think is a true representation of you. The sort of two things that I love most in dance music are really great house and really great techno, and they require and induce very different sorts of atmospheres. If you’d ever been to Germany in the 90s and played house music in a techno club, it got quite nasty. I’ve had cigarettes thrown at me and all sorts. I played in Berlin about ten years ago, and someone came up to me right whilst I was in the middle of the mix and reached forward, sort of like: “I just want to say to you that I am so disappointed.”

Like a parent shaking their head and walking away going, ‘you’ve let us all down tonight.’

[Chuckling] I tried to reassure him: “it’s okay for you to be disappointed, don’t worry about it.” There are some people that just desperately want me to play my own music, but if I’m being booked as a DJ I feel it’s too arrogant to play my own music. I think by this point a lot of dance music should be made of watermelons and Ford Fiestas and the Liberal Democrats, yet I really struggle to find that. Although I’ve just been sent an amazing record by Cassius Select on UTTU, which is so exciting if only to hear different kinds of noises and new sounds. So that presents another challenge, of not just falling back on old records that I’m familiar with.

It’s a tension between wanting to represent a really coherent manifesto for what you think dance music can be on that particular day, but also wanting to not take it too seriously and just have a fun night off. I’ve been accused of being a party pooper many times; you definitely don’t want to ruin people’s night out just by playing obscure records for the sake of it. Having been in a lot of nightclubs over the years, hearing the same kind of sounds go round in the same ways, you want to break out of that but you also understand the patterns and what works. There ends up being quite a lot of friction in it for me. Thankfully though Dance Tunnel was wicked. Alongside another recent one with Gilles Peterson and Black Coffee, definitely one of the best parties I’ve played in London for years.

“All I can do is look wistfully out of the window and hope some of this makes sense.”

Given all the different impulses you’ve channeled down various avenues through the years, are you constantly playing against former iterations of ‘Matthew Herbert’ in everything you do in life? That must be quite fatiguing.

Yeah, it is. I mean I’m 43 now, left with a sort of feeling that I’ve always taken a slightly more difficult route. The other way would have led to so much more money: from adverts, or just concentrating on DJing or big bands tours. I could have sold out a long time ago you know. There’s not a lot of money to be made out of bombs exploding –

– well no, there is, just not sampling it.

[Laughs] True! I could head to the arms industry instead. Even then I copped a lot of shit: some people think it’s exploitative or disrespectful; some think it’s an issue that should remain silent; some just think you shouldn’t do it, full stop. I’m finding as I get older that it’s harder to knowingly keep tying your hands together to do stuff, and I guess that’s part of the joy of being able to make this record how I know. Of course when it comes to recreating it live or DJing, you start wondering which bits of music from your past to play, or whether you try and introduce people to new sounds and ideas. So then you’re back to bumping your head against that friction again…

What’s behind the tactic of using still-life video reveals for every single track? It feels like you’re shaping the narrative while you still can for the next nine-odd weeks; wringing the last bit of personal ownership out of the record before it’s out there in the world.

Directing and making videos for the album has been really nice. Something that’s changed in our lifetime is the way people watch music instead of listening to it, and one of the things I find most disturbing is going on YouTube and seeing people rip a track of mine and place an image with it. That’s weird. So I’ve enjoyed taking back ownership of that process. Although it’s funny, because it’s already gone wrong. We used the highest-rated Vivid film stock we could get for “Middle,” and lit it as hard as we could without making it too bright – and it’s come out too dark. So a couple of people gave feedback within thirty seconds going, “nah it’s a totally shit video, you can’t see anything.” So I was sat there like, [melodramatic wail] “aaargh, it’s started again!”

You’ve just got to view all these distortions caused by the internet with a wry smile and quizzically raised eyebrow. People could pick up on things in any given order, say using a DJ Koze remix with slinky underwear girl as the avatar, and run with it from there as their interpretation of ‘Matthew Herbert’. You can’t truly do anything about it.

For me the worry is always that people will make a judgment about me and my music based on hearing just one or two pieces of it. I guess you try and create a virtual world – with a cinema, an abattoir, a playing field, a swimming pool and a church or whatever the musical equivalent of those is – and you invite people to come and live in it for a bit. I’d find it sad if people only ever stayed in the Premier Inn on the motorway outside and never made it further in.

The real black sheep of the family is “Café de Flore.” It became a track played out a lot in Ibiza, then we licensed it to a lot of different compilations, and now you hear it in lifts and lobbies all over the place. I heard it in Harrods the other day at Heathrow Terminal 5! It sort of gets everywhere and I find it unsettling that I’ve created a piece of fluff just designed to make people feel that everything’s alright in the world; that it’s okay to buy overpriced handbags. Then again, while it came from an honest ‘falling in love with Europe’ kind of moment in my life, it was written for a Yves Saint Laurent fashion show for fucks sake, so I can’t get too fussy about it.

So fuck it, really all I can do is make the music. Because it’s a public gesture it’s up to the public to ultimately decide which bits live, and which bits die; which bits work, and which bits fail; which bits I should never have done, and which bits I should have done more of, or what have you. All I can do is look wistfully out of the window and hope some of this makes sense. You have to accept it and tell yourself it’s okay, and if it’s going to appear in these other forms around the world then you have to hope they will eventually lead someone further down the ladder to the dark, miserable recesses of hell at The End of Silence. [Laughs]

As someone with a deep investment of thought into the implications of repurposing of source material on a micro level, what’s your reaction to that writ large with the Marvin Gaye ruling?

I think it will probably have an impact on that big mainstream pop stuff simply because the money involved is so huge, but sampling has always been a shortcut to authenticity. I’m not entirely sure they made the right decision about “Blurred Lines,” but when you see it in the context of all the other Marvin Gaye material that Robin Thicke’s ripped off you think, ‘well, he had it coming’. If they were making music out of the sounds of UKIP instead, you wouldn’t have that problem. If the music had re-imagined itself in one of its former guises – wanting to change the world for the better, say – instead of a base ambition to just make people feel ok for three and a half minutes or to, like, fuck pretty women, then maybe it wouldn’t encounter those sort of difficulties.

It’s ironic that that pervading laziness is what accidentally destroyed him twice over. A throwaway comment in an interview admitting that he and Pharrell had deliberately tried to replicate that vibe lost them $7m and change.

Wait, he said that in public? I didn’t realise that!

Tasty, tasty schadenfreude.

Wow. I hope nothing in this interview’s cost me $7m.

– Matthew Herbert played Boiler Room in London on Tuesday 7th April alongside Photonz, The Maghreban and Damon Frost. For all recordings, head HERE –