September carries a heavy cultural weight around mexicanity and the “Grito” festivities. Mexico’s streets become decorated with fiesta miscellanea, and tri-coloured flags are scattered everywhere to celebrate another year of the country’s own identity. Apart from all this annual folklore, September also serves as a chance to look back into the cultural happenings that formed the backstory to Mexico’s musical present. The Tapatian capital, Guadalajara, has a curious story behind its current cultural health of electronic music. In justice of the fourth version of our Uncover Sessions series held in the lands of Jalisco, it is important to revisit some of the key moments behind the movements moulding the present-day identity of the city.

Just like any other metropolis in Mexico, at some point between the 80s and 90s, music based on drum machines and synthesizers seeped into the hypnotism of music; all due to an exposure to foreign products conceived in the U.S. and Europe. The only difference between Guadalajara and the other cultural hotbeds of the country like Mexico City or Monterrey is that Guadalajara’s assimilation process was much more turbulent: a story about struggle for creativity and freedom of speech. Today, after years of friction between the local authorities and the rave subculture enthusiasts, the integration of electronica into the community is irreproachable. Jalisco has become a take-off strip for many of the most celebrated Mexican veteran troupes. Guys like Luis Flores, founder of the Nopal Beat label and Aztec techno ambassador of the old world, or the distinguished house à la subterranean Ibiza figure, Hector are key examples.

This assimilation process has not only created an incubator for artists speaking the universal language of dancefloor-focused music genres. New and unpredictable fusions arise within the new generations of producers via a negligence of the old school aesthetics. An illustrative example is the 20-year-old Niño Árbol, a member of the new wave of producers that tug at a number of modern sub-genres to forge their own sound.

This project, just like many other initiatives in Guadalajara, is proof of a modern Mexico; fresh and novel, yet a clear reinterpretation of the classic sounds that acted as catalysts for many veteran producers. A similar example would be Macario, the Static Discos regular who has achieved the construction of electric four-on-the-floor narratives with an inexplicable sense of nationality, or the visual art of Smithe (illustrator of our flyer artwork), who has captivated personalities that are so remote to Mexican culture like Pharrell and Flying Lotus. Even Juan Moreno, who has adopted the aesthetics of legendary selectors like Delano Smith and Larry Heard in his very own production genetics.

These are all examples of how modern-day Guadalajara lives a present bathed in the aperture and acceptance of multi-format art, but this was not always the case. This is why we sat down with one of the figures that lived this change throughout the last three decades. Enter Luis Flores.

BR LATAM: How did your interest for electronic music start off in Guadalajara?

LUIS FLORES: During a period between 1987 and 1989, the people who came to define the whole electronic movement in Guadalajara were already doing something. One of them, Jorge HM (El Calambrín) was doing radio, programming Ministry, Skinny Puppy, industrial, etc. He was playing in a place that had a huge role within this movement. It was called Ricks. One day, all of a sudden, someone decided to open a venue for alternative music from scratch. There was nothing else like that, and Jorge was the resident DJ there. My friends and I didn’t know him. We were about 15 years old. We all decided to stick around him. After that, we decided to join Radio Universidad in 1999 while we were still very young. The nature of Radio Universidad was very inclusive and, because they paid miserably, for us to fill up a slot with a semi-decent program was good enough for them. We started programming industrial music with Alejandro Dávila and Sebastian Veytia, with whom I later started the Nopal Beat record label. After that, we started a show focused on alternative music, and that’s when we shifted to techno and house.

How was the public reception for this radio show?

We all had a background from Ricks. It was all around a really small bubble, yet we covered a lot. It wasn’t only industrial. Industrial was really important for us because it was the ideal music genre for teenage troublemakers with a certain political notion. It was new, anti-state, angry, etc.It was a very specific identity. If you identified with it, it completely filled you up at that age. We had the show for about four years and it had a huge impact in the city. Up until now, there are still people who have discussion groups about the show on Facebook. It was a serious response. We then left the show and started the alternative side of it, and it was about the time that danceterias started happening. These were basically raves that changed location every week. The staff was made out of the same group of people that I worked with. In no time, it became a success. These were parties for about 2,000-3,000 people, every Friday and Saturday. The music was techno, acid house, and all of the spectrums that were mixed back then. The night had many phases, and Calambrín was in charge of it.

“You could find the poshest people in town hanging out with transsexuals. Ecstasy was new and everyone was with the kindest attitude”

What year are we talking about?

This was at the beginning of the 90s. It was a prototype for rave culture. It was in sync with everything that was happening around the world. It became so popular because it was a very inclusive matter without any kind of prejudice, just like things are supposed to be. You could find the poshest people in town hanging out with transsexuals. Ecstasy was new and everyone was with the kindest attitude. Eventually this grew to the point that a powerful member of the Opus Dei pressured the police to raid on what we were doing. I mean, what we were doing was illegal so we really couldn’t complain. That’s when the beef started between the law and what we were doing. The people who were throwing parties ended up opening a club. The government decided to give them some licensing deals to avoid them fighting back. The other people, like Jorge, were still behind throwing parties because of what it all really meant; all the romanticism behind it.

We were still doing events and we got to see a very specific answer from the police whenever they found out about them. They already had the “go” to raid anything that looked like a danceteria. We experience raids with massive amounts of people in the events, and just about when they started, the police made everyone strip down and make them do sit-ups. Something incredibly…

Twisted.

Yes. Once I went to a friend’s birthday party, and the police received a hint about it being a dancetería, even though it was a private party. Those dumbasses not only messed up by showing up to a bautizo one block away from the party, they even arrested two innocent guys that were there. Shortly after that, they found where our party was and it got real tense. “This is private property! It’s a birthday! What’s your problem?” They couldn’t care less until they took two people. It was like that for the whole decade. It went all the way through the 2000s.

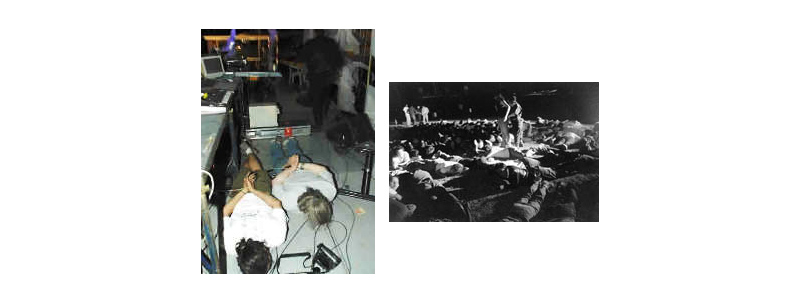

Tlajomulcazo, Guadalajara, 2002

Was it in 2000 that the situation cooled down?

It seemed like it. We started doing events at Roxy, which was the cultural and alternative space for excellence. They even had the permits. We could do whatever we wanted there within a certain curfew. We tried doing everything as legal as possible but it was always a mess. That was about the time when we started doing Nopal Beat. We started out doing those events, and it kept on growing. A friend curated a festival where they were doing stages for psycho, house and techno, and with our own stage. A type of festival without an international headliner, it was a great time to do it.

It was an event that was going to be huge. There were about 1,000 people inside and another 2,000 people about to come in, and the police decided to show up. A new government official had just started out his period, Ramírez Acuña. That guy later on became the secretary of government who also won the medal with that whole thing around the war against the narcos. That idiot steps in the government and says, “How can I show everyone I’m going full throttle and say that I’m the guy in charge?” He finds out about the rave and, like the good idiot he was, he was still thinking about what was happening ten years ago. He sent in a squadron of 2,000 officers to the rave. They get there and… well… you know how police treat people here. They were touching the women and hitting the kids.

Abuse.

Complete abuse. They made everyone lie flat on the ground and wouldn’t let anyone go. They threatened us. Everyone who was outside did get away though. Obviously we were already speaking to the press. A friend who was a DJ there was randomly picked out of the bunch and said he was selling drugs. Those assholes took eight people like that. Luckily for us, we had a friend who was working with the federal police department. Through him, we bailed out our friend that same night. Just when he stepped out of the building the judicial police pulled out the guns and well… the classic stuff. The thing is he got out. He told us that the police made them hold bags of drugs so they could take photos of them and made them sign a declaration. Also, two big-balled 18-year-old kids decided not to sign the declarations and went straight to jail.

“The level of love for art is very exaggerated, like a sickness.”

They didn’t want to confess. Since enough time had passed, there were preppy kids who went to our events that had parents that knew the way around the law and people from college, people who didn’t think electronic music was outrageous anymore. The next day, all the newspapers exposed this guy as an animal. They really fucked him up through press. We had a meeting with the governor and the kids’ lawyers where we asked him to get them out. Back then, there was a TV show called Círculo Rojo on Channel 2, where Aristegui had her show. Just when I was in that meeting, I got a phone call from them. They invited me to the show the next day to speak about electronic music in Mexico and the repression behind it. I was looking at that guy’s face and I said, “Fuck yes.”

The next day, I went on Círculo Rojo and national attention poured down on him. A year later, a friend from the press who was working at the city’s office told me, “We set up a manifestation a week later in front of the government building, on a Sunday, with 6,000 people, sound, a rave, everything. Every year we repeated that. By the third one, the Office of Culture was already financing it as a cultural manifestation.” After that, all the free events took place in Guadalajara, two versions of Mutek, Richie Hawtin, etc.

So, in a way, all this friction you had with the government helped to consolidate the community of electronic music.

Yes, exactly. That was the reason all this movement was respected as a cultural expression, even more than in any other place in Mexico. All the support that the government provided around free events was huge. These were events with 20,000 attendees on the street. At the same time, Tijuana had Nortec and Static Discos, D.F. had MUTEK, and everything was a cultural phenomenon. Finally, Guadalajara had music and events that where actually worth it.

Guadalajara Dance Laboratory 2009, rave in honor of the Tlajomulcazo raid

Before or after all this, you also absorbed the role of a promoter. Why does this necessity arise?

I think the majority of people that have been in electronic music for a while need to try all of it. If not, who is going to promote your record or gig? Who is going to book the artist you want to see? Everything is so personal. If nobody else does it, it has to come from you. I’m not even a notable example. Everyone throws their own event, releases their own record, curates their own radio show. The level of love for art is very exaggerated, like a sickness. In the end, you become the main investor always. Luckily, we had the chance to get the support from the government where, instead of risking everything, we had bestial budgets which meant we didn’t have to compromise anything lineup-wise. It was also free, so the people would just go to hear “risky” artists, and they responded to it. These were productions where nothing was missing. After that, I started working on my personal approach to techno, and I wanted to do more specific things at local clubs, booking friends in them who eventually became local heroes. I mean, we don’t have a Berghain, but we have references that come pretty close to it.

You are the only Mexican that has ever played Berghain. Why do you think that there are so few locals that have reached this point of acclaim?

Unfortunately, this is more of a symptom that the country has, not because of the lack of talent or interest. Mexico is designed to fuck you over and for everything to be difficult. More if, for some ridiculous reason, you decide to get into the arts. I’ve had the luck to do this for enough time and have a family that supports me. Apart from that, I know a lot of people who are making really good music, but find it hard dedicating the time it really needs to reach a certain level. Mexico seems to be isolated from the global electronic scene because of our language. It is very curious because there is a better electronic scene here in Mexico than in the U.S. by far.

This is because our club and party curfews are way more flexible and there are stable clubs. The U.S. is still the reference for American electronic music because they speak English and, at some point in history, a lot of things happened there. In Mexico, for starters, you think you are already fucked. It’s about creating relationships here and, with people over there, generating bridges that are not there naturally. When you are in the U.S., those bridges do exist through magazines, websites, history, labels. This link does exist over there, even though it is not as big as the one in Mexico. We are not thinking of translating everything into English, because we have no idea how to do it and because they do not plan to learn Spanish just to see what is going on in Mexico. This keeps us pretty separated. The line has always been playing music, hosting radio, creating a label.

“I think that Mexico is very dark. It is the love of my life but it’s a disgrace, a constant tragedy”

You mentioned everyone ended up doing everything à la DIY. Is this why you started Nopal Beat?

The idea of starting a label first came to us in 1999. I think we started to compile tracks for a release, printing vinyl and promoting them. Back then, there was no big electronic label. We put out the first compilation through Opción Sónica, the country’s only independent label of excellence for a very long time. This curiously happened just about the same time that WFM created its electronic format on a national level. Everyone wanted their electronic sub-label within their major imprint. We signed with EMI, right when IMECA started doing their thing, just like Nortec. For major labels, it seemed to be the response to the descending numbers within sales. Artists were producing like fabrics. They weren’t big bands that were difficult to transport. It was something very practical for them, even though they had no idea how to market it. After that, we all went through the cliché troubles of migrating from an independent to a major label, catalogue recuperation issues, etc. This happened to us, it happened to Nortec, and well… we ended up being independent again.

Around 2005, we stopped printing because people stopped buying our releases. We did a pause and started doing techno. Ever since, I’ve been dedicating all my energy to my project. When we decided to stop doing the whole label thing, we opened up a house that has served as our headquarters for more than ten years. It’s a very big house in Guadalajara and at some point everyone had their studios there; recording studios, production studios, Sussy 4’s studio, etc. La Nopalera. We decided to start a music school there eventually, and we’ve been doing that for five years. We started out Beat Lab to promote the movement. In a way, there has always been a flux of people in that house and the instructors are always changing. The space is always alive.

A lot of people say that techno is notoriously more accepted in Guadalajara than in other parts of the country, like D.F. or Monterrey.

I think that Mexico is very dark. It is the love of my life but it’s a disgrace, a constant tragedy. If there is place has things to criticize and things to yell about, it’s Mexico. This is why techno lives up to be a great vehicle for it.