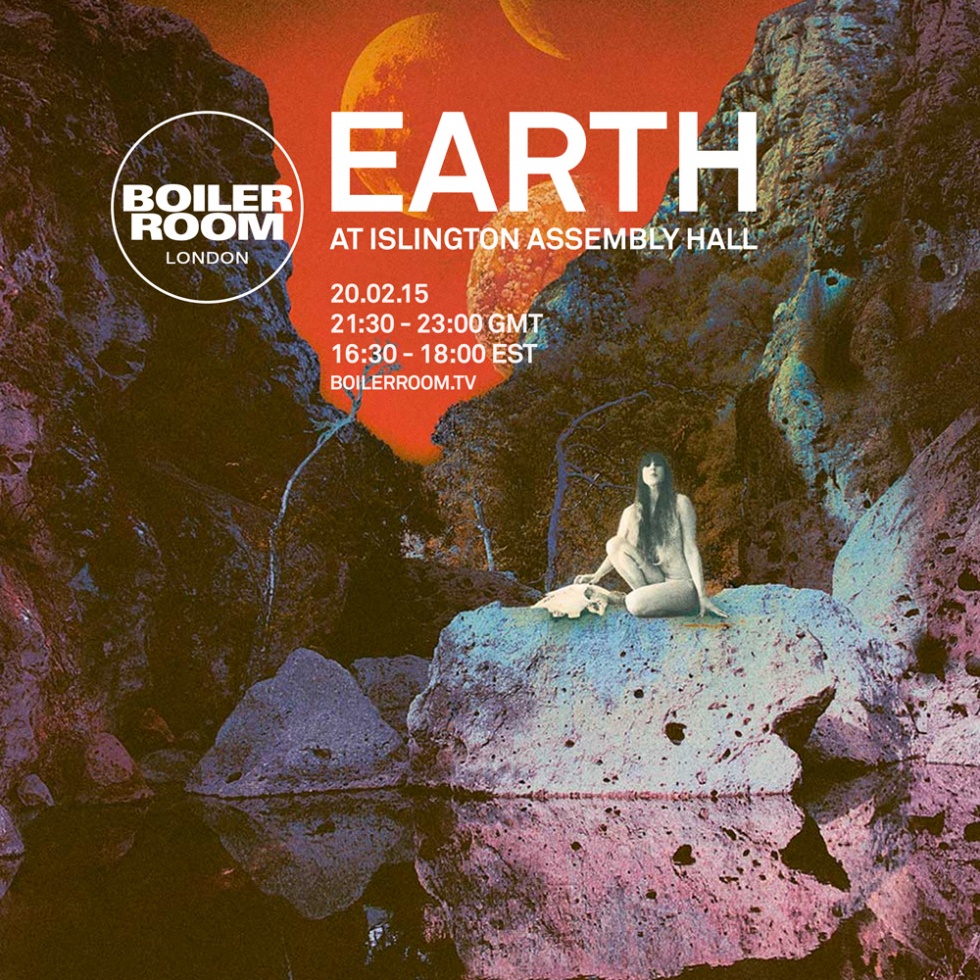

As we prepare to broadcast a show this Friday by the mighty Earth, Louis Pattison digs down into the band’s deep roots and opens up a portal to unending darkness.

As we prepare to broadcast a show this Friday by the mighty Earth, Louis Pattison digs down into the band’s deep roots and opens up a portal to unending darkness.

—

Doom-drone is the rock genre that doesn’t so much rock as crush, inexorably, until all light is extinguished. It takes the downer vibe of heavy metal and both distills and subtracts, removing choruses, solos, often even vocals, plunging the music into an inhuman realm of dark abstraction.

If this is your first encounter with doom-drone, first it helps to understand about where it comes from. You can trace the roots of doom metal all the way back to Black Sabbath – who took hard rock, made it sludgier and slower and filled it with misery and paranoia – but the sound really solidified into a genre in the ‘80s with groups like California’s Saint Vitus and Stockholm’s Candlemass, who took Sabbath’s down-tuned, oppressive clang and distilled it into something almost romantic in its sustained, inky-black gloom.

Dylan Carlson grew up a teenage metalhead, but at the same time was studying minimal music.

Drone music, meanwhile, grew from a very different source. Defined in the 1960s by composers such as La Monte Young and Tony Conrad, whose experimentation in the field of classical minimalism found them exploring influences such as polyphonic vocal music, Indian tambura and the Scottish bagpipes, drone is a sort of catch-all term for a classical, extended tone-based music drawing on influences far outside Western traditions.

Both genres would seem to be worlds apart – one from the dingy rock club, one from the rarefied world of experimental classical music – but they share something in their love of extended compositions, sustained atmosphere-building and intense hypnotic power. And the man to bring them together was Dylan Carlson.

Born in Seattle, Washington, Carlson grew up a teenage metalhead, obsessed with Sabbath, Ted Nugent and a sludge-rock trio from nearby Aberdeen named The Melvins. At the same time, though, Carlson was studying minimalist music, and the group he founded in 1989, Earth, was dedicated to melding the two styles to make a metal music that privileged slowness, heaviness and extreme volume. “For me,” he told me back in 2006, “Earth was always about taking that La Monte Young, Terry Riley thing and presenting it like a rock band.”

Earth have made many great records over the years, but in particular their 1993 album 2: Special Low-Frequency Version is the cornerstone on which drone-doom rests. Three tracks and 75 minutes long, its glacially slow riffing and thick, saturated low-end roar feels predicated on the notion that heavy metal can be ambient music, too.

Released on Sub Pop at the height of grunge, Earth 2 sold poorly and didn’t fare too well with rock critics, who struggled to disassociate Carlson’s experiments abstract, ultra-slow guitar minimalism from his struggles with hard drugs. (Perhaps understandably: Carlson himself has described 1995’s Phase Three: Thrones and Dominions as the sound of “utter despair, desperation and madness”, and it’s rumoured that a Sub Pop employee had to lock a strung-out Carlson in the studio they’d hired to get him to complete the recording.)

Following the ZZ Top-goes-drone moves of 1996’s Pentastar: in the Style of Demons, Earth went on hiatus while Carlson was embroiled in various drug and legal problems. But Earth returned in 2005 with a clean frontman, a new line-up, a new, cinematic sound. Comeback album Hex; or Printing in the Infernal Method drew on the books of Cormac McCarthy and the vulture-pecked Americana of Neil Young’s Dead Man soundtrack, while 2011’s Angels of Darkness, Demons of Light I and its 2012 part II were inspired by the folk-rock of Fairport Convention and Carlson’s investigations into the “faire folk” of old English mythology.

These records may seem to have diverged from the quintessential doom-drone sound of Earth’s 1990s records, but that early sound is the foundation of everything that followed and the sense of the suspended or eternal can be felt rumbling through all of the 2000s/2010s releases. And Carlson’s recent – and hopefully ongoing – collaboration with Kevin Martin aka The Bug eminently proves that his love of experimentation with gut-busting rumble and drone is undimmed, and still has the potential to create elemental sounds.

Earth’s influence has spread far and wide, their sound a template that other acts have picked up and run with. Toronto’s Nadja take Earth’s lumbering slowness and spin it out into something incandescent and dreamy, with notes of shoegaze groups like Slowdive or Ride. Moss, from Southampton, share Carlson’s love for fantasy, playing a gnarly guitar-and-drums doom with lyrics that draw on themes of occultism and the cosmic horror writer HP Lovecraft. New Zealand’s Black Boned Angel, meanwhile, go darker still, blurring the lines between doom metal and dark ambient, with repetitions that seem designed to blot out all hope.

Japan, meanwhile, has been a fertile breeding ground for drone-doom. Tokyo’s Boris, while experimenting with many different permutations of rock music, have pursued a drone-doom direction on albums like 1998’s Amplifier Worship and 2005’s Dronevil (a double album, one disc ambient tinged, the other heavy, and both designed to be played simultaneously). And of course their Dommune show with noise terrorist Merzbow last year turned Boiler Room to Boiler Doom in style. More mysterious are Corrupted, a long-running group from Osaka who shun interviews and photoshoots, but play a cinematic doom of grandly epic scope, interlacing their crashing riffs with occasional acoustic segments, Spanish-language vocals and, on 2005’s El Mundo Frio, a harp.

Outside of Earth, though, the key band in drone-doom is undoubtedly Sunn O))). Formed in Seattle in 1988 by Stephen O’Malley and Greg Anderson, the duo named the group in tribute to their primary inspiration Earth (it’s also a reference to the powerful brand of amplifier, which Dylan Carlson had already singled out for admiration on the Earth live album Sunn Amps & Smashed Guitars). As a starting point, Sunn O))) take the ultra-slow, ultra-heavy drone of Earth 2 and added a heavy dose of ritual; live, O’Malley, Anderson take to the stage in monk’s robes, bowing to one another through clouds of dry ice as each monolithic, drop-A guitar riff clangs from the speakers at staggered intervals.

The core characteristics of doom-drone are simple: slowness, repetition, volume, relentless blackness

Some have noted Sunn O))) sound like a conventional metal album spun at three revolutions per minute. The musician and author Julian Cope, writing about the track “Richard” from Sunn O)))’s debut album ØØ Void, described it as “14-and-a-half minutes of distant seagulls flying over Porton Down, in southern Wiltshire, before being accidentally sucked into some ground-based experimental jet engine, after which their ghosts rise up and screech for ever and ever in the eternity.” It sounds like it could be difficult music, but in fact a Sunn O))) live show is enormously effective on a multi-sensory level. You don’t just hear them, but feel them, waves of sound passing through your body and rattling your ribcage. It is, perversely, massively pleasurable music.

If Sunn0))) have proven remarkably enduring, though, it’s surely because of their skill at adding to this simple template. As both a studio and a live entity, O’Malley and Anderson approach their band as a project with open ranks. “My Wall”, from 2003’s White 1 featured Julian Cope reciting ancient druidic poetry, 2005’s Black One made heavy use of the black metal musician Malefic – even locking the claustrophobic vocalist in a funeral casket to capture his screams on “Báthory Erzébet” – and 2006’s Alter was a full-album collaboration with Boris that also included Kim Thayil from Soundgarden, Earth’s Joe Preston and violinist Eyvind Kang. More recently, Sunn0))) teamed up with ‘60s crooner turned avant garde composer Scott Walker for the collaborative LP Soused, and while it was clearly more Walker’s record than Sunn0)))’s, their low-end drones fit in perfectly.

Meanwhile, both Anderson and O’Malley deserve individual mention, as both sit at the very centre of doom-drone’s tangled family tree. Both played in the short-lived but influential groups Thorr’s Hammer, Burning Witch and Teeth Of Lions Rule The Divine (the last one also featuring Lee Dorian of Cathedral). Anderson has played in the progressive doom group Ascend, and runs the forward-thinking metal label Southern Lord from California, who release Earth’s albums to this day. O’Malley, meanwhile, has played in a staggering number of side-projects, collaborations and one-offs, including the terrifying Khanate, the improv-inclined Aethenor, and KTL – a duo with Peter Rehberg of Editions Mego that blends doom and experimental electronics. The core characteristics of doom-drone might be simple – slowness, repetition, volume, relentless blackness – but there’s a whole dark universe here to explore once you dive in.

Louis Pattison’s Essential Doom-Drone Recordings