Let’s make this clear straight from the off. Hip-hop wouldn’t be the same without J Dilla, and that’s no gross overstatement.

From the boom-bap of Slum Village to the neo-soul movement he pioneered as part of the Soulquarians, Dilla’s musical fingerprints linger everywhere. As an artist ahead of his time—and a unique hybrid of producer, rapper, songwriter, and singer—Dilla amassed a staggeringly deep discography over the course of his career. The life, sound and soul of Jay Dee lives on today through the records he created with the likes of A Tribe Called Quest, Common, Janet Jackson, D’Angelo, and De La Soul, to name but a few.

Perhaps even more remarkable is the way in which his musical legacy continues to grow even today. In the years since his passing on February 10 2006, his contributions to music have leapt from the background into the foreground.

February 7 marks the tenth anniversary of Donuts, the 31-track magnum opus that Dilla produced from his hospital bed in Los Angeles. Countless tributes, beat tapes, and interpretations of Donuts are proof of the way it resonated. An essential listen, it’s regarded by many to be Dilla’s crowning achievement. In the years since its release, the project has only grown in legend.

To mark the decennial of Donuts and Dilla’s passing, we pay homage to one of the greatest producers to ever do it by speaking with his family, friends, and close collaborators. From Dilla’s brother Illa J to his closest musical friends in Frank N Dank, what follows is an insight into what the legend James Dewitt Yancey meant to those who knew him, and to those who channel his energy today.

From Conant Gardens to the world.

ILLA J

“James will always be my big bro. We both grew up in a musical family so our musical connection was there long before I recorded any song over my brother’s beats. Technically my first recording with my brother was when I was 13, but it extends way beyond that. I just miss my brother James.

I was always writing, since I was eight or nine, but I never had the courage to have my brother hear some of my stuff—especially since he was professional at it. When I finally had the courage to say some of my raps in front of James and my other brother, he was like, “Okay, I’m going to get you some studio time.” It was a surprise when he sent a limo to the house with some money in it, and I had a session at the studio scheduled for me.

That was the first time I ever recorded, and even then he taught me about rapping. He gave me little pointers. He wouldn’t necessarily change my rhymes or anything, but he would say, “Maybe you want to put some space there,” and other things like that to make my delivery right.

“He was what you call the complete package. He produces, sings, raps, writes songs, performs—everything.”

So much of his work is production, but he was also really good writer. He also had a good singing voice, but he just never got a chance to do much of it in his solo stuff. He was what you call the complete package. He produces, sings, raps, writes songs, performs—everything.

Choosing my favourite Dilla production is always the hardest question, but I would have to say “Runnin’”. When it came out it was such a big moment. It was when a lot of good things started popping up and you realised, ‘whoa James is really doing this on a big level’. It brings back so many memories because it became the theme song for New York Undercover. At that time that show was a pretty big deal, and that theme song was big! Everyone was like, “Yo, James’ song was on New York Undercover, that’s crazy!”

The music video for “Drop” came out around that time too, and when we would order videos on The Box we would order that. I was about 9 years old in ’95 and I knew what was going on, but not in depth. I didn’t quite realise the impact he was making on music.

Looking back James seemed more like an industry secret. If anyone knew him, it was from Slum [Village], but people didn’t know a lot of the production he did until later. People have gone back in time and checked all his music, like “Oh I didn’t know he did Tribe, I didn’t know he did this, I didn’t know he did that.”

You can think of it negatively, but in a crazy way it’s better that it happened this way. Being an introvert, I don’t know if he would have been able to handle the fame. Dr. Dre was the first ones who to be recognised as a producer that rapped.

When Kanye did The College Dropout, that was one of the times where they took a rapping producer seriously. Technically, my brother was ahead of all that. ”

BAHAMADIA

“J Dilla was, is and will always be our culture’s preeminent sound designer. In terms of producing as an electronic musician, no-one else has/had the ability to compose tunes or articulate compatible cadence, colour, tone and structure the way he did. What Jay was able to accomplish by mastering his gear is barely descriptive beyond brilliance.

Personally though, I favoured him as an MC. I recall seeing him rock it live at Saint Andrews (which was also the first time we met pre-Soulquarian days). Slum were on stage rocking and suddenly they all formed a circle around the mic. As the track started Jay-D was up but couldn’t remember the verse. So he pulled out a black and white composition book and like clockwork WENT IN! T3 and Baatin followed suit as if they had rehearsed the choreography and all.

“Amazing, humble, a genius. J Dilla.”

Needless to say he became an instant choice for my all time top five favourites. Period. A few years later, I had the honour of working with him on a remix for my BB QUEEN project. I had also started to receive custom joints from him for my then upcoming LP.

I still have those beats and got a chance to spit the verses and hook to him at Jazzy Jeff’s studio. He snapped like a kid on some basement backpack shit.

He never gave the vibe that he was superior; he was just an authentic b-boy from the “D”. It was a trip how he moved like he was ‘normal’, but he was the furthest from it. Amazing, humble, a genius. J Dilla.”

ERIC LAU

“I could write a book about Dilla so I will keep this short. Dilla was a master and is the greatest teacher to music makers of this generation. He changed the way musicians play and how music is made today. I can’t really express how much his music has inspired me and how much it has helped me in my life.

All I can say is that whenever I listen to his music, it makes me feel great and uplifts my spirit. It’s always a great day when I hear a Dilla beat that I haven’t come across before, and I wish I could hear all his music again like it was the first time. In his short time on this earth he left us with so much music and that is a testament to his dedication and incredible work ethic. I pray that I can contribute even 1/1000000 of what he did one day.

Much love to the whole Yancey family and those who continue to spread his music to world.”

B+

“For a lot of personal reasons, my favourite picture of Dilla was the one I took of him and Madlib on the floor. The fact that we managed to get Dilla out to Brazil was a really big deal. We didn’t realise how sick he was, but I knew the trip meant a lot to him. Ma Dukes told me and Eric [Coleman] how much it meant to him. Just to get him there; even if he was only going to be there for a few days.

He had to go home on an emergency flight, but that was one of the best things to happen through my photography.

I was screening a film at a music festival, and they asked us to help put together a show to close out the festival. They were interested in getting Madlib down there, and we had ham there before back in November of 2002 to make a film called Brasilintime. Madlib was already a Brazilophile, and so it didn’t take much to convince him to go and dig for records. When we were making the Brasilintime, the first sample we could find was Dilla flipping “Saudade Vem Correndo” for Pharcyde’s “Runnin'”.

“We thought it would be amazing to get Dilla digging in Brazil”

We thought it would be amazing to get Dilla digging in Brazil, talking about Brazilian music and how it would be an amazing addition to the film. When the opportunity came for Madlib to go to Brazil for the show, we all went to lunch and got Madlib on board.

When we were driving Madlib back to his crib, we were like, “You can bring a DJ, there’s room to bring people with you,” and I don’t know if it was from me, Eric, or Otis [Madlib] himself, but it was on everyone’s to bring Dilla. [Madlib] called Dilla, and everyone in the car could hear how excited he was.

A month later we were all on the plane to Brazil. Dilla was really sick, but he never used to talk about that shit. We visited him in the hospital when he was in a coma, but he would always play it off. I remember picking him up on the way to the airport, and I remember him walking out to the van, and being like, “Wow, he’s fucking fucked.” But he went to Brazil, and it was just remarkable to see him there. He looked different, and to be honest the flight there nearly killed him. We got him out of the hotel to go digging at a record store right by the hotel.

I just took a few frames of him and Madlib looking at 45s, and remember Dilla going back to the hotel and playing them for me, Otis and Eric. It was terribly tragic because the next day we had to put him on a flight home, but for those few hours it was kind of magical.

To have the opportunity to help a cat go somewhere he clearly had an affinity with was amazing.

Dilla died like a year later. We were there in April 2005, and he died the following February. At the funeral, Ma Dukes told us “You guys looked after him in Brazil, and you don’t know how much that meant to him”. After the trip, all he would talk about was Brazil and how amazing it was. For us we were a bit upset like, “Dilla, don’t put your life at risk on our account. If you’re sick don’t fucking travel and shit, because god forbid.”

He was super grateful to have an opportunity, but that photo was just…It was just such a fucking great, historic moment to spend those few days, so that was my favourite.

To me, you can speculate about cats being able to channel, being able to link to something beyond. Madlib didn’t learn that in school. How did Dilla channel that rhythm? It’s just one of those magical things. There’s something about cats that listen that hard. African-American cats that listen that hard, that you can’t explain it in words.

That’s one of those beautiful examples.”

PHAT KAT

“One of my many favourite moments with Dilla was when we recorded Dedication To The Suckers EP. We recorded it in its entirety in 90 minutes, and still had time to hit the strip club.”

“Dilla was the the most Yoda-esque producer I’ve ever witnessed.”

DAVE COOLEY (ELYSIAN MASTERS)

“Dilla was the the most Yoda-esque producer I’ve ever witnessed. The wildest part of working with him was that he never did anything twice. He was so skilled and able to commit to personnel, takes or mixes with no second guess. His mind’s eye held a map to the final arrangement at all times, and he would always reach “X marks the spot” in the fewest steps.

One time J ran through a series of mutes/dropouts with me during a mix, and he would just call each one out, measure by measure, trimming drum elements and muting specific tracks with micro-precision.

He systematically ran through them like a boot camp obstacle course, nailing each one as he went, without ‘trying’ or touching up any of them. In about 5 minutes he had completed 20 or so drops, each with slight variations on the 30 track elements. Then he just sat back and said “that’s it…” with a wry smile and a sideways head nod. Looked like he spent maybe one or two calories on it, just a cinch for him.

I miss him very much and I could swear he’s still here and listening in while we’re working on his back catalogue to this day.”

KARRIEM RIGGINS

“J Dilla’s music is still so inspiring to me. I feel honoured to have had a chance to work with and known such a beautiful soul; the person who created this amazing sound and set the bar extremely high for music. I remember recording drums for Fantastic Vol. 2 on the song “2u4u” and recording a take which I didn’t think was any good. Before I had time to enter the control room to listen back, he had already mixed the drums. Genius!”

OH NO

“I first met Dilla at the Jaylib video shoot. It was the joint with Frank N Dank and Wildchild. It was early in the morning and I was starving after smoking, so I went to check the food truck. Dilla was in there tearing some donuts up. From there we were just tripping, like, “Oh shit, that’s Dilla!” and he was like, “Oh shit, that’s Oh No!”

He already knew who I was and he actually had a couple of my records. From there I invited him to smoke a blunt and he was down so we chopped it up in the car. He was like, “let’s do a joint, let’s do something,” so I said, “what’s up with a beat tape,” and history was made from there.

After “The Move”, I started going out to LA all the time. The medical card just got popping, and we were hitting a new spot everyday. After we would hit the spots, we would stop by Dilla’s and smoke him out. He would give us mad beat tapes and stuff, and I was telling him, “I got crazy games and shit, I just made a controller.” He said he had to come through and see that shit, and he literally came through a couple days later.

We were actually playing MAME (Multiple Arcade Machine Emulator) and I was showing him all the arcade games I had. We were playing Punch Out and other random games. He was definitely a gamer though, playing Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas and I was hooking him up with codes. Unlimited life and all that. He had the Playstation, and he bought a computer from my homeboy that had pretty much every single arcade game on there. I’m pretty sure he was going to chop up all that music.”

KAYTRANADA

“To me J Dilla is easily in the top five to ever do it — dead or alive. I learned about Dilla through ATCQ when I first heard “Find A Way”. That song was so hypnotic to me and was the turning point of my musical taste. Someone later referred me to the beat-tapes (MPC3000 & 64 Beats), where I think you could hear the best of him. During my high school days, I was banging them tapes every day and enjoying it because there was nothing like it at the time. There were a lot of copycats lurking on the Internet, but no-one even got close. The music was so great that I couldn’t study for my exams. It’s all good though. I was studying Dilla instead.”

MASEO (DE LA SOUL)

“My last encounter with Dilla was in Detroit during the very last Okayplayer tour. After the show I rode about 30-40 minutes to his house with Frank N Dank. I spoke on things that he was a little reluctant to discuss, which actually brought us closer together. He didn’t think I knew about the lack of acknowledgement he’d had for a lot of his Tribe productions. I spoke about it in so much depth that he was actually both relieved and elated. He kept turning to Frank N Dank saying, “Ayo, you hear this nigga? You hearing this nigga? PREACH nigga!”

It seemed new to him that he’d be hearing this from somebody outside his close circle; outside the family. I mean his extended industry family as opposed to his nucleus family. I also got to build more with his fam—Ma Dukes, Karriem Riggins, and Dez Andrés. It was a serious night; a good night.

The discussion about him not getting his due kind of opened up a Pandora’s box. The song credit issue never really went away, but it was acknowledged in a big way that night. That night brought a lot of instant validity to what he was trying to explain to his D fam in private over the years.”

LEFTO

“On December 8th 2005, I invited Jay Dee, Rhettmatic, Frank N Dank and Phat Kat to Ghent, Belgium. It was Dilla’s last tour, and we all remember him performing in a wheelchair while killing it on the mic. He stayed two more days before leaving for the United States and I got a phone call from his tour manager asking if I could bring my MPC to his hotel room. I had a black MPC 3000, which was Dilla’s favorite drum machine.

Dilla was weak, laying in bed with gloves on, but once he saw the MPC it’s like he found the strength within to slowly stand up and sit at the desk in his room. He had a little iPod sound system, and the cable [plugged] right into the MPC. And there he was making a beat!

In the photo you can see a shirt around Dilla’s neck. The shirt said ‘Get Well Soon Dilla’ and was signed by everyone in the room that night. I gave it to him on stage.”

KING BRITT

“I remember it being either 1999 or 2000. I was working on Sylk130 Re-Member’s Only at Larry Gold’s studio in Philly. I was in Room A and Common, Ahmir and James Poyser were in James’ studio. James had come in to record some piano and vocoder bits for my album, and Common heard the vocoder like “whoa”. James borrowed the Korg VC10 until he got his.

That same week, I saw Dilla sitting on the couch so I properly introduced myself. He was very cool and said he liked “When The Funk Hits The Fan”. He was there working on Electric Circus with James and crew. A very innocent meeting and a humbling experience.

My favourite Dilla track has to be “Purple (J Dilla/Ummuh Remix)”; so slept on as one of the hardest beats.”

FRANK (FRANK N DANK)

“I met Dilla in 1986. I was in 6th grade and he was a grade ahead in 7th grade. I moved into the neighberhood, but he and Dank and a couple of the other homies had knew each other from elementary school. As middle school kids, there wasn’t him making beats or anything. Our friendship built from there, and we became what people would call best friends.

I was there for most of the significant moments when he first started making beats. Me and him actually first started DJing parties before we started making beats. He taught me how to DJ, and then we started doing parties. That’s how we made our high school money.

At that time he started messing with beats, but not with machines. He had two dual cassettes that he would make beats with. From there it was a gradual progression. We were all dancers, so of course we would dance a lot and do our little parties. Then me and Dilla would DJ the neighborhood parties for all our friends, and it just progressed from there. For a long time I was only DJing, then Slum convinced me to pick up a microphone.

I can’t pick a favourite Dilla production, but I really dig “Breathe and Stop”, it’s an amazing production. The version that Q-Tip put out had a different arrangement and was mixed by Q. The original Dilla did—the one we used to ride around to in the truck—was a little dirtier and different. “Breathe and Stop” is really crazy to me.

I was lucky enough to be able to be a fly on the wall for tons of situations. We were in New York, Manhattan in ‘99, early 2000s. Dilla was mixing Like Water for Chocolate with Common. He got a call from Q-Tip, who was like, “Yo, where are you at? I’m at Sony Studios, come over here. I got something I need to show you.” Me and Dilla hopped in the cab, went over to the studio. Tip was recording Amplified, and Tribe had just put out The Love Movement.

We went over to the studio, and for me, I was like, “Ooh, I’m about to hear some brand new Tip shit.” I had heard bits and pieces Dilla would play for me, but not like this.

“We walked in the studio and Janet Jackson was sitting on the couch.”

We went into the studio and Tip was like, “I got a little surprise for you. Something I want to show you.” We walked in the studio and Janet Jackson was sitting on the couch. This was before Dilla and Janet did the record, and she had a gigantic sex book. Her and her girl were sitting there reading it. For me it was so crazy. I was just looking and staring at her. It was everything you saw on TV—the voice, the smile, the smell, all of that was right there. I had to look at the board to stop staring at her.

On top of that, Tip was playing his new album with all these Jay Dee productions on them. Dilla was just chilling. He was in control and cracking jokes with Janet Jackson. I was like, “Nigga, you so controlled chilling with Janet Jackson. Are you crazy?!”

Q-Tip and Ali did the original of “Got Til It’s Gone”, but never got credit for it because that’s how the music business was back then. Dilla got the remix. It was a rare thing that he got that remix. They actually put that remix on two separate singles—like the single after that, the remix was on the b-side of that too. That’s the meeting that made the remix happen.”

DANK (FRANK N DANK)

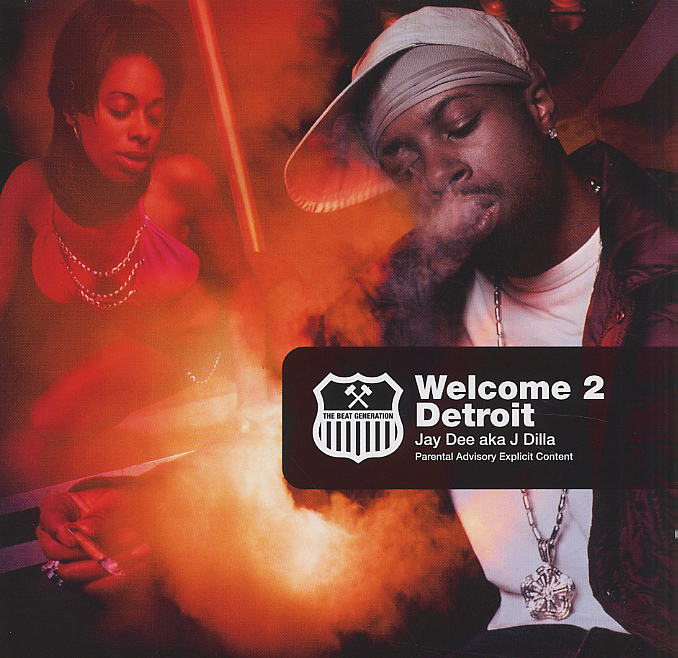

“Dilla liked to go to the strip club seven days a week. Seriously, it’s not a game. Chocolate City. The energy. We did the Welcome 2 Detroit album in there. After we left there and had a good time, we would go straight to the studio. He would immediately put his headphones on and ask “Yo Frank, Dank, y’all got some shit?” Then he would take the headphones off and click the sub button to turn the music on. We would be like “goddamn” and bang out to the morning.

“We worked for years in the basement to come up and resurface. Blood, sweat, and tears.”

We’d wake up and have one rolled up for him; turn on the music, mix it, and ride out to it. We would record two songs a night, pop a bottle, mix and master it the next morning, and put it away. We worked for years in the basement to come up and resurface. Blood, sweat, and tears.

Dilla’s studio was at the crib. You weren’t coming to that motherfucker. It was invitation only. After we built the studio in Dilla’s crib, niggas weren’t coming in there. You had to be really privileged to come there.

Another story involves my first trip to New York with Dilla. Common was making Chocolate for Water. Guess who was in the studio session…?

Legendary engineer Bob Powers. Wendy Goldstein, my A&R for MCA Records, Black Thought, ?uestlove, Jaguar Wright, Hi-Tek, Talib [Kweli], Common and Dilla. You know who came in the door? Motherfucking Dave Chappelle. Dilla was just smiling and laughing and shit. Then I went outside and Busta and Case were just chilling. I’m starstruck; literally tripping but trying to keep my composure.

Dilla laughing and shit, like “I told you nigga.”

—

This week, to mark both the 10th anniversary of Donuts and his untimely passing, we’ll be presenting a special podcast about the importance of J Dilla’s all-time classic.