Earlier this Spring, Boiler Room brought together a handful of musicians from the L.I.E.S. and Styles Upon Styles camps in a dusty New York space for a 100% Hardware showcase: all live, all analogue, and all artists with a firm grip on their sound and aesthetic. The recordings of Gut Nose, Person of Interest, Certain Creatures and Gavin Russom are available now (hit the hyperlinks), and below is a deep dive into the whys and wherefores of what they do.

Struck by the continued coherence of this specific aesthetic in this specific locale, we asked NYC-based writer Gabriel Herrera to think about where it’s come from, where it’s going, and what it all means. Why New York? Why analogue synths? Can you be an outsider when your ultra-limited 12″s are currency for wealthy collectors? How can a scene that refuses to be defined sustain its identity? Find out, if not the answers, then at least a few even more interesting questions below…

—

Genre is a much more confused and confusing concept than it once was. Certain corners of electronic music in the early 21st century have certainly begun to form identities distinct and sovereign from the mainstream, but these remain extraordinarily hard to get a handle on. We’ve seen highly specific styles linked to inanely broad-seeming genre names – for instance, the post-Night Slugs Club Constructions aesthetic collision that’s daunting to label beyond the catch-all term “club music,” or the vast range of experimental sounds that get blanketed as “power ambient.”

The most notable (or detestable, depending on your level of cynicism) of these terms, “outsider house,” denotes an impressively robust grouping of producers and labels that have distinguished themselves through a dedicatedly reactionary approach. Embracing analogue hardware – or software that can approximate analogue sounds – has informed a swath of contemporary productions rooted in an oblique mix of house, techno, and noise.

Artists at the periphery of club culture are almost invariably drawn towards the center

By now you’re likely familiar with some of the labels peddling these sounds – Bill Kouligas‘ PAN, Ron Morelli‘s L.I.E.S., and Will Bankhead’s The Trilogy Tapes are probably the most prominent – and their heads, who’ve been quasi-canonized as “outsiders” in a few short years. It’s funny to consider how that often-derided genre name that initially brought many of these artists and labels together in a journalistic sphere is now little more than the punchline of a few Twitter jokes.

Yet, there’s an undeniable social and cultural cohesion to the output of these collectives. The mutual interest in DIY aesthetics distinguishes these artists from the mass markets of electronic music and is essential to their ability to flourish peripherally in the first place. As ever, the familiar notion of the “underground” gets co-opted as a marketing strategy by a booming dance music industry, and promoters everywhere scramble to sell exclusivity with a price point to match. Artists at the periphery of club culture are almost invariably drawn towards the centre, especially if they want to play live to more than a cultish local audience.

Members of all the aforementioned labels have had sets at Berghain / Panorama Bar, Ron Morelli has played larger-scale clubs such as Brooklyn’s Output; Bill Kouligas curated a two-week music festival around his label, including performances at MoMA PS1’s Warm Up. In some senses these bookings signal voluntary membership in the club establishment, but on the other hand little has changed in terms of how the music presents itself as independent. The hyper-limited edition white labels are still abundant, as are cassette releases…and the price tags haven’t gone down yet, either. Through an uncompromising aesthetic vision – or maybe a stubborn one – the music endures.

What makes these artists capable of earning continued attention within such marginal spaces without getting drawn into the mainstream? It makes sense to consider the artists themselves: as Bill Kouligas points out, there exists “a very false and very seamless narrative of how art and music comes together stylistically and conceptually,” which his work attempts to resist. “It is funny to me,” he continues, “as actually this approach seems far more honest and organic than artificially attempting to present seamless ‘scenes’ that only exist once the curator, or journalist, decides to.” It seems Kouligas might be in on the Twitter jokes as well.

They arrive at stylistically linked sounds through diverse – and sometimes perverse – methods.

So far, the audience and press have failed to assimilate outsider house into the neatly-organized canon; there is not yet a neat notch on the subgenre belt. And read almost any interview where a musician associated with outsider house gets asked their opinion on the moniker, and you’ll find that none of them answer kindly; with indifference, at very best. These are all, like Groucho Marx, people who refuse to join any club that would have them as a member. In fact, part of what makes artists on labels like PAN and L.I.E.S. so fascinating is how they’ve managed to arrive at stylistically linked sounds through diverse – and sometimes perverse – methods.

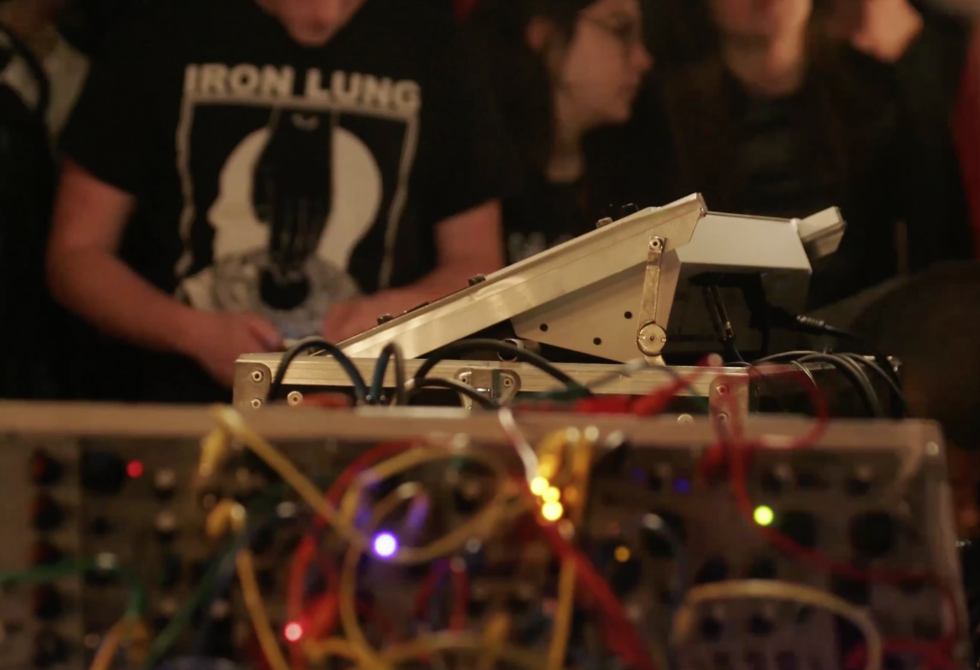

Take California native and L.I.E.S. mainstay Bookworms, whose analogue setup you can see in the Boiler Room showcase, is a far cry from his early days programming kickdrums using Music Generator on the first Playstation console. Bookworms’ eventual transition to an MPC resulted in his biggest track yet, “African Rhythms.” More recently he’s adopted a number of synths which have opened up a wide range of possibilities, like working with label mate Steve Summers – who introduced him to Morelli in the first place – as Confused House. Bookworms’ ability to migrate between myriad analogue and digital interfaces, especially by moving backwards down the chronological spectrum of technology, suggests an indifference to production history as a linear thing.

Then there’s Gavin Russom, a lifelong musician with a background in composition and the technical expertise to build and repair synths for James Murphy and tour with LCD Soundsystem. Add to this a discography spanning more than a decade, and Russom’s pedigree admittedly exceeds most of the artists on L.I.E.S. Despite that, Russom’s modest 3-track 12” on the label, Mantle of Stars never overstates itself and humbly draws from a wide range of sonics, from squelching acid to spectral horror soundtracks. Having only joined the family this year, his hardware expertise makes his detailed synth psychedelics seem right at home on the label. Hardly formulaic, L.I.E.S. gathers talents from unique backgrounds with the common urge to experiment and dodge conventions.

New York’s contemporary history as an incubator for alternative dance music (to say nothing of its history with decades-worth of precursors) has helped to stir the creative conditions necessary to grow a label like L.I.E.S. Without the availability of niche venues like Bossa Nova Civic Club and Body Actualized Center, and semi-legal warehouse venues such as Trans-Pecos and 285 Kent, it is challenging to imagine bringing together producers with similar artistic whims.

“There’s nothing interesting to me about the world of digital.”

This is especially true when so much hardware-driven electronic music resists making its presence focused on the internet anyway, thanks to the aforementioned proclivity towards white label vinyl releases and cassette tapes. Morelli himself has accepted digitally releasing his label’s music with a great deal of reluctance, noting that “[i]t kind of defeats the whole purpose of it… [t]here’s nothing interesting to me about the world of digital.” With Morelli’s move to Paris, however, and the label’s recent focus towards artists outside the United States, there has been space for other labels and artists to continue harvesting New York’s underground electronic talent.

Styles Upon Styles, an imprint best known for its strictly-curated Bangers & Ash series, is one such label, having continued to showcase new talent from New York’s electronic music periphery. Artists who release on Bangers & Ash must create one conceptual track on side A, with an accompanying club-ready track on side B. The A-side of Certain Creatures’ first release on the label features a collaboration with Stuart Argabright of Ike Yard, a mid-period Factory Records band caught at the overripe end of No Wave. The ease with which Argabright’s vocals punctuate Certain Creatures’ angular rhythms indicate a welcome dialogue with past generations of alternative electronic music in New York that Styles Upon Styles is championing, and in this case, directly facilitating.

In like manner, their release of Gut Nose’s Filthy City also seems to vaguely call upon the past as a reference point for contemporary music, although in this case hip-hop is a more important primer. In its best moments, Gut Nose sounds like DJ Premier instrumentals run through a paper shredder underwater, which pushes it even further past already blurred genre boundaries. It’s some of the label’s most exploratory work yet, and perhaps most indicative of what’s to come.

While the current era of idiosyncratic producers making distorted electronic music might resemble the forbearers of house and techno in their attraction to analogue interfaces and the lack of conventional precision in their work, they differ from the parent scenes considerably in collective memory and attitude. Once house and techno were acknowledged as legitimate and established forms of music, they were celebrated; artists made house music tracks about house music. As mentioned earlier, though, most contemporary artists who get pinned with the outsider house label would openly reject it.

Somehow, it frees people up from the “paralysis of choice” while retaining choice

This handful of artists has corroded genre conventions in a way that’s opened up more possibility for a nuance in a musical ecosystem so polluted with taxonomies that they’re nearly meaningless. Somehow, it frees people up from the “paralysis of choice” while retaining choice – and paradoxically returning to the foundational and essential within club music in its use of analogue equipment.

If these artists so strongly avoid historicising and classification, will they and their cultural infrastructure survive in the long term? Truthfully, the answer for many could be no: they might just retreat into the background and fly under the radar without anyone paying attention to them historically in the same way that they have for artists who we identify with labels like Chicago house or Detroit techno. They might become actual outsiders, making noise for nobody.

Ultimately, though, that’s part of what makes the music exciting: the small pressings, low exposure, and distorted lo-fi techniques that all seem to signal their own potential demise. How can you not consider a music scene in somewhat apocalyptic terms when Bookworms has a track called “The World Is Becoming A Wasteland?” This hard-nosed attitude has made clear that the emphasis is less about placing the music on a timeline or in a category, and more about developing personal significance for every track.

Outsider house, or whatever people will call it years from now, will survive simply because it means something different for every person listening to it. As we all ascribe personal meaning to the art we consume anyway, maybe this belligerently “non-genre” genre might just be the most honest approach to categorisation, and perhaps a scene that flirts with doom and even denies its own existence might be the most perversely viable kind of cultural movement for the information age.

– All photos by Nathaniel Young & Matt Sherman –

– For all recordings of the 100% Hardware showcase, head HERE –