We’re always interested to hear from Slimzee. This is, after all, the quiet man of grime: one of the most important innovators in UK music of the past 20 years, the DJ and producer who became a vital lynchpin of the scene as it gradually coalesced at the beginning of the 2000s, but with a public profile close to zero and a distinct aversion to the promo and publicity game. He’ll happily come and shell down a Boiler Room session as he did at our recent Eskimo Dance spectacular, or at the launch of Rollo Jackson’s Slimzee’s Going on Terrible film, but we never expected anything approaching a Q&A with him.

So when BR contributor Melissa Bradshaw said she had sat down with him for a lengthy chat, and did we want the transcript, we sat up and took notice. When she told us that he’d opened up about the OFCOM bust and subsequent ASBO which effectively ended his pirate radio career, and about the nervous breakdown which had followed and kept him away from music for more than half a decade, we had to pinch ourselves.

Here, then, is a history of London’s most vital music from the man that was there at the heart of it from the very outset. It’s a story that had to be told of roof-climbing, culture clash, egos, cat-and-mouse games, institutional stupidity and, ultimately, redemption. Read on…

—

Slimzee didn’t normally have the radio gear in his house. But something had happened to the car they used to move it around. So that one time in early 2005, the flyers, cords, and transmitters were in his hallway.

“They raided my house. They come and they said ‘let me in, it’s [name of officer]’. That’s the DTI geezer: or OFCOM, they’re called now. Got through the door, they just jammed it. I was like, ‘oh, what is this?’”

Pirate radio was soon to be eclipsed by the internet, but back then it was still thriving. And the media regulator OFCOM and the pirates were at war (DTI was the Department of Trade and Industry, who were the people chasing the pirates until OFCOM’s introduction in 2003). And Slimzee, then 26, was the most important DJ on pirate radio.

He grew up on Roman Road in Bow, East London, and was hooked on music and the pirates; Kool FM, Pressure FM, Weekend Rush. He went to Bow Boys, the same school as Wiley. “He used to wear a Cowboys jacket, do you remember that? I had the Raiders one.” At school he spent his dinner money buying dubiously-acquired records from his mate Mega. “I’d buy them for like £2, with my dinner money, and go home and just play them, and I used to like it. And then finally I got decks and Wiley would come to my house, and his Dad had a studio as well, and so we started getting into the music.” Wiley has said that Slimzee both introduced him to jungle, and switched to garage before him. In 1994, with mates Geeneus and Uncle Dugs, Slimzee co-founded Rinse FM, running the station for 3 years from his bedroom.

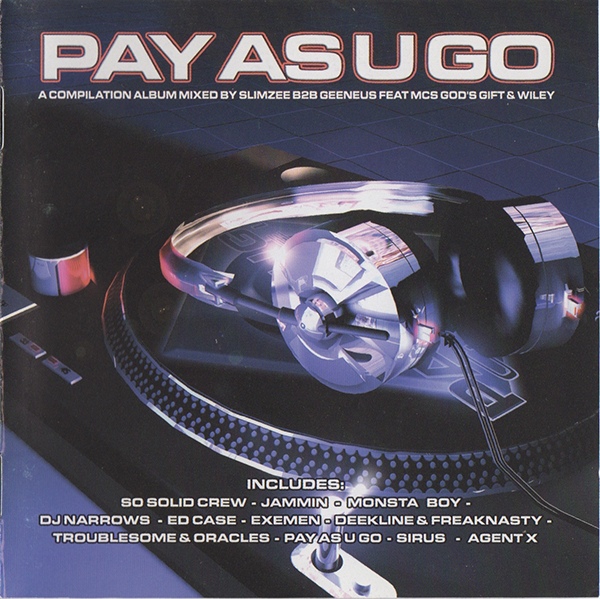

In the late 90s, Wiley had a crew called Ladies Hit Squad, and Slimzee’s was SPP: they joined to form the legendary garage crew Pay As U Go, with Plague, Major Ace, Wiley, Maxwell D, Target, and Geeneus on production. (God’s Gift, Flowdan and Breeze would join later). Along with the So Solid And Heartless they were changing the game, making garage into something newer and tougher.

From 1997 Slimzee had started playing jungle records slowed down (at 33 rpm instead of 45) and mixing them with darker garage by Wookie, Master Stepz, El B, and Zed Bias. “I liked the MCs spitting on my set, Pay As U Go lot… Plague, God’s Gift, Wiley, Maxwell D, Major Ace. Dizzee Rascal used to come on my sets a lot. I just used to get a buzz out of doing it and playing stuff they could MC to. Some people in the scene didn’t like me doing it, when I got a little name. They were just saying you’re making the scene go darker and all that. I’m not saying no names!”

“Not saying no names” could be a reference to the legendary meeting where significant members of older garage generation had a meeting to try to stop the sound that Slimzee was pushing. “I was on the station at Rinse and I put up little leaflets I’d photocopied in Rhythm Division, saying about my sets on Sundays, and they just took them down. But after a while I started playing tunes what weren’t garage, dark tunes. It started getting big from there.”

“I was playing it in a few clubs, and some people would look at me like ‘what’s he playing?’ But I was making that music as well, it was future music.”

By the turn of the millennium, a number of producers were pioneering a raw, stripped down sound, rebelling against mainstreaming garage’s glitz and glamour: grime. Slimzee recalls when Jon E Cash came up when he was playing at one of the legendary Sidewinder raves, and gave him a dub: “War”. “I was playing it in a few clubs, and some people would look at me like ‘what’s he playing?’ But I was making that music as well, it was future music.” He’d play “War” on the radio, twice a Sunday, and “people started going mad for it.” He was the only DJ who had it, 2 years before its release.

Pay As U Go worked the radio and raves, headlining huge events like Milton Keynes Sidewinder and London’s Garage Nation. Wiley’s entrepreneurship at this time is legendary. “Wiley used to go to Rhythm Division with new tunes and they would buy them off him for £5 a record, or was it more,” Slimzee says, smiling. “And kids would buy them for so much, because they would just love them. He’d press up 2000 and straight away he’d have them all sold. There and in Blackmarket and Uptown, about 5 shops. So he made a good profit off it.”

But it wasn’t just Wiley who was selling records. Among Slimzee’s fans was Plastician, who had a job selling records to shops. “Slimzee could sell a record by playing it,” Plastician says. “I could sell a box of anything that he had played on Rinse or Sidewinder tape packs. Living in South, I used to physically have to sit still holding an aerial to listen to Rinse FM when Slimzee was on Sunday afternoons. But as a DJ, I had to listen every week, as there was no other DJ in the world who had access to the dubs he did around 2001.” That year Pay As U Go scored two chart hits with “Champagne Dance” and “Know We”. Among the many thousands of people watching what Pay As U Go were doing were Rapid and Danger, also from Bow, who in 2001/2002 started making beats on their PCs and formed Ruff Sqwad. The fuse was lit.

Slimzee’s 2002 Sidewinder mix with Dizzee and Wiley was a landmark, and reminds one of the absolutely vital documents of early grime. Then there were tensions with Wiley. In 2001, a club night called FWD>> had started, intended as a space for producers who were experimenting with 2 step. Meanwhile Wiley was promoting his own Eski Dances. In this interview in 2003, Wiley talked about being kicked off Rinse and then let back on Slimzee’s show. “He gets really pissed off when other people have his tunes,” said Wiley, “but only him having the tunes doesn’t really help my record sales”.

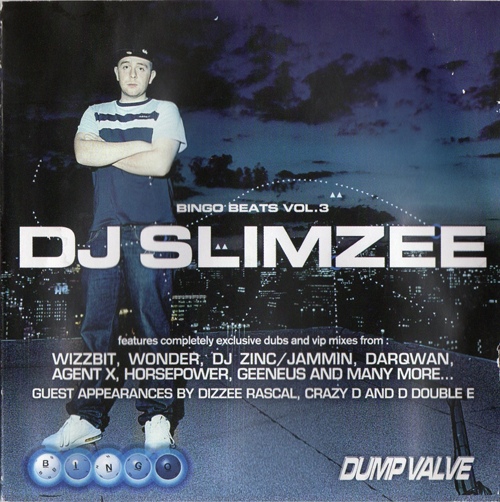

Slimzee was playing more “that FWD>> music,” said Wiley, claiming, perhaps provocatively, that “he’s over there, but really I know he’d like to be over here”. FWD>> of course became known as the first home of dubstep, but a mix of stuff was always played there, including breakstep, as on Slimzee’s 2004 mix for Bingo Beats. In 2002 Pay As U Go had disbanded and Wiley formed Roll Deep, who would go on to sign to Relentless Records. But for all the tensions, personal and sonic, between Wiley’s “Eski beat” and “that FWD>> music”, Slimzee and Wiley continued to work together, even heading to Japan together in 2004 (“I thought, oh they’re not gonna like it — but they liked it,” says Slimzee, drily).

It may have pissed Wiley off, but Slimzee keeping his record bag so exclusive kept it very special – so special, in fact, that people from outside of London would actually drive to the city so they could tune in to his Sunday afternoon shows on Rinse. There’s no doubt that Slimzee’s willingness to test the audience, his taste for murkier sounds and instrumentals, and his relentlessly tight mixing definitively contributed to the birth of grime. He has been called “the undisputed king” of the DJs in grime’s infancy.

“I was playing Dizzee Rascal’s “I Luv U” on dubplate and people were looking at me going, what is this? And the next year it was one of the biggest tunes.

The tracks Slimzee rolls off as he reminisces about this period of innovation include Dizzee Rascal’s “I Luv U”, Wonder’s “What”, and Wizzbit’s “Jam Hot”, and of course Youngstar’s “Pulse X” and “Pulse Y”. “I was playing Dizzee Rascal’s “I Luv U” on dubplate and people were looking at me going, what is this? And the next year it was one of the biggest tunes. I was too advanced for other people.”

Logan Sama, who would go on to have one of the biggest grime shows of all – on Kiss FM – also joined Rinse around this time, on the 7pm Friday night slot before Roll Deep, and credits Slimzee for helping him make his connections. “When it’s Slimzee who is introducing you, the producers were always going to be forthcoming with the music.” Slimzee also contributed to Plastician’s career (at the time he was Plasticman). “His shows inspired me to start writing beats,” he tells me, “and eventually I sent a CD to him via Rhythm Division. I still remember him texting me asking for the tunes exclusive. It didn’t really get bigger than that for me. I was really buzzing when I got that text, proper heart stopping. That’s how much of a big deal it was to get your tunes played by him.” Slimzee signed two of Plastician’s tracks to his label Slimzos (reissued last year on the Plasticman Remastered compilation).

In 2003 Dizzee Rascal’s Boy In Da Corner won the Mercury Music prize. Slimzee received a gold disc for his contribution to the album. In 2004 Wiley released Wot Do U Call It? on XL. By 2005, when OFCOM bust down his door, Rinse were the biggest pirate radio station in the game, and Slimzee was at the epicentre of a grime scene grappling with the contradictions of being newly celebrated in a world whose institutions – the police, OFCOM, the legal system – were prejudiced against it.

“So I got done for it because I had all the stuff in my house.”

You can’t help but wonder that there weren’t some people in influential places who just didn’t like the success. But, as Slimzee is quick to point out, it wasn’t just war between the authorities and the pirates. It was war between the pirates that caused the bust too. “Other stations would go up there and do dangerous stuff, they would like smash up the block. When another station would come on our roof they would mess it up, and throw bricks, and do weird things, drill holes, leave the door open, break the locks. They were sabotages, set at your radio gear. So the council would try and nick you, they would wait for you.” Slimzee says he never got involved in this kind of sabotage, but gives the risk of it as the reason the council wanted to shut them down – though OFCOM’s stated reasons for pirate radio’s illegality are diverse.

“They took my phone, all my computers, they went through all my records. They were saying ‘you’re gonna do years, you’re going away.’”

Soon the council found another method. In 2005 Slimzee was up on the roof of Shearsmith house, a 24 story tower block in Shadwell, putting up a rig. “I realised there was like a little spyhole, you’d never noticed, but there was a tiny little hole. And I was like oh what’s that? I just put a little bit of tape over it. And that’s how they got me, because they got a few pictures of me. It was just so small, like the size of a nail, a little hole.”

What happened to Slimzee after that day the DTI bust down his doors seems completely incommensurate with any wrong he had done.

“They took my phone, all my computers, they went through all my records. They were saying ‘you’re gonna do years, you’re going away.’ I was like, it’s only pirate radio, we’re trying to help people out. Listen to music and stay off the streets and stuff. It weren’t breaking… well, I know it was breaking the law. But we were trying to help our listeners.”

Slimzee went to court and was given an ASBO (Anti-social behaviour order), a form of civil sanction introduced by Tony Blair’s “tough on crime, tough on the causes of crime” government in 1998. But one of the criticisms civil rights campaigners have of ASBOs is that they eroded the distinction between civil and criminal law, allowing local authorities to unfairly criminalise people. In 2005, according to the Broadcasting Act 1990, pirate radio broadcasting was a civil, not criminal offence.

“Yeah that’s what it was like. They were saying ‘you might be going away.’ I went court. I got a £500 fine and an ASBO.” As he remembers the ASBO restricted Slimzee from going above the 5th floor in any building (this has variously been reported as the 4th and 5th floors). Breaking the terms of an ASBO could mean up to 5 years in jail.

“After that I got ill for a bit. I had a nervous breakdown. Not a lot of people know that. And I stopped music for a little while.”

In fact, he doesn’t necessarily think the ASBO gave him the breakdown. “I always suffered from bad nerves. It just comes out in you.” But after he was threatened with prison, no-one offered to help Slimzee find a way to carry on his DJing career legally. “No there was nothing like that [support]. So I just went my own way. I went down.” Whether or not his breakdown was triggered by his bust, there is no doubt that it took away what had been the focus and structure of his life, and made it far harder to escape the dark place he was in.

“I knew it was illegal, but we just used to do it because it was so good. Go in your car, listen to it while you’re driving. It was a good thing, it used to give me a buzz.”

Slimzee says he “wasn’t good at school”, except at music (he got an A at GCSE, “but that didn’t mean nothing because it wasn’t compulsory”). Whatever he may have struggled with, radio had helped. “I knew it was illegal, but we just used to do it because it was so good. Go in your car, listen to it while you’re driving. It was a good thing, it used to give me a buzz. Once you’d got off it you’d wanna go straight back on. It kept you going. It helped a lot of people, more people listened to it and then… it was good.”

He does remember violence and problems at raves – in particular one in 2002 or 2003, “I was just ducking down, people were throwing bottles and Dizzee Rascal was just going mad. That was in Manchester, Havana club.” And he doesn’t deny, of course, that there were problems in the pirates. But when the police shut down a grime event and will not discuss why, are they actually doing their duty to protect the people that put on and go to grime events? The police didn’t try to shut down football because of hooligans. The message from OFCOM was clear, though. They told him that “they wanted to shut down the pirates, and they wanted to make an example out of me.” The Evening Standard reported that Slimzee was caught on the surveillance cameras “after a year long hunt by OFCOM and Tower Hamlets officers”.

In 2006 The Wireless Telegraphy Act made it a criminal offence to broadcast radio without a licence, punishable by up to two years in prison and an unlimited fine. Perhaps the worst irony was, at the same time local authorities were putting on DJing workshops that musically emulated precisely what the pirates were doing. During the time Slimzee was unable to work for Rinse, Sarah Lockhart, the driving force behind record label Tempa, Bingo Beats and FWD>> (and responsible for many crossover garage signings before that) moved to the station as station manager, after becoming mates with Geeneus. In 2008, when she was campaigning to get Rinse a license, referring to those DJ workshops, she told me “It’s like, you’re telling us this is illegal and it’s really out of order, but you’ve just fucking simulated it with the government to try and interest the children!”

For a long period after 2005 Slimzee became something of an urban legend – he’d still get a few bookings to play at events and his name was always whispered with excitement. There was a myth that he was the first person to get an ASBO; actually nearly 2.5 thousand ASBOS had been issued by 2004. (It was more likely it was the first ASBO of its kind).

One of the people to book Slimzee was Andy Musgrave, owner of the Bristol club institution and now label, Crazylegs. Andy says when he was 17, 18 years old Slimzee “was one of my heroes,” and after booking him for a series of events, “I became aware that I could quite easily help him to get more gigs, and more recognition for what he does”. Slimzee now has Andy as his manager, Rebecca Prochnik at Elastic Artists as his booking agent, and a show on NTS radio which he has now been doing for over a year, while building a “Hall of Fame” on his soundcloud. “I haven’t had to do a lot,” says Musgrave. “Everyone knows who he is. Everyone’s got a lot of respect for him.” It’s true there can’t be many DJs who had news items written about them when they started up a Soundcloud page.

As grime enjoys its renaissance, Slimzee also proves how flawed followers and likes are as a measure of influence. Unlike figureheads like Wiley or Skepta, he’s not a self publicist (apart from when he’s DJing exclusive dubs with his name on them of course), always happy to operate in the background – but every bit as significant in his way as those big names. If Wiley is a National Treasure, and Skepta a Prodigal Son, Slimzee’s rightful title is The Godfather.

He really loves it when someone gives him one of those special dubs (“I used to have Agent X ‘Decoy’ with my name [called out] in it,” he says with obvious pride), and having the radio show and more bookings means people are sending him their tracks again. “Now everyday I wake up and I’m getting tunes sent to me, I’m now like I was back in 2001, 2002, getting all the new stuff in, doing raves and trying to break tunes.” Only now it’s a whole new set of names: Trends, Dullah Beatz, and Mystry are among his favourites.

photo credit: hark1karan

So much is different now of course – the internet especially has changed all the parameters, altering radio and allowing access to scenes so they aren’t locked down the way they used to be. Perhaps the most emblematic of the blurring boundaries was when Rinse FM finally got a license. Last year, though, with the Anti Social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014, ASBOS were replaced by a new set of civil injunctions and orders, which extend local authorities’ powers of control. Civil rights campaign group the Manifesto Club warn these can definitely be used to discriminate against music.

On the brighter side of things, Slimzee says there aren’t the same problems with gangs at raves and the crowds are more diverse. Asked for some moments in the past year when he’s really noticed grime taking off again, Slimzee says Jackmaster’s residency at XOYO, Bestival, and a show in Portsmouth that reminded him of Sidewinder in 2002, albeit with a whole new crowd (as you can see on this Facebook video).

“If I get booked for something commercial I gotta play like Skepta ‘That’s Not Me’ and some D Double E, I don’t mind playing them. But I love instrumentals.”

Last summer filmmaker Rollo Jackson took Slimzee back onto the roof of the tower block next to Shearsmith House (they had to settle for the one next to it because of an aerial). They were filming for Slimzee’s Going On Terrible, a film that Rollo said he wanted to make because Slimzee was an icon of his growing up, and “brought so much sheer joy to all his listeners”. Among all this, though, one thing definitely hasn’t changed. “If I get booked for something commercial I gotta play like Skepta ‘That’s Not Me’ and some D Double E, I don’t mind playing them. But I love instrumentals.”

Those early days were the best days of his life, Slimzee says. And he’s proud of what he and his peers achieved: “because of grime, now everyone looks to London to see what’s gonna be the next thing.” He’s happy again now, though: you can hear it in his voice. “I’m getting younger fans now, I thought they’d be all 40 by now. But I’m getting younger fans every day, it’s really good. And then they listen back, they go and do their homework, and they find about the scene, and go back and listen to the old sets. Things are coming around, and I want to be a part of it. I want to get back to that Number 1 Spot.”