It’s true. What is a dance space without good sound? Much has been said about what contributes to a solid system, but we rarely stand back and admire the actual aesthetic of our favourite speaker stacks. As UK soundsystem culture turns 60, Joe Muggs examines the form, function and artistry of speakers in depth, with additional interviews by Laurent Fintoni – Funktion-One, Broad Axe and Positive Sounds all feature. A suitable lead-in to our upcoming Deep Medi session next Tuesday.

—

Great sound reproduction is vital. From the first Jamaican dancehall systems – brought to the UK for the first time 60 years ago this month by “Duke” Vincent Forbes – through the Klipschorn speakers put by David Mancuso into his own home for the Loft parties that created disco culture as we know it; through rebel sounds like DiY, Desert Storm and Spiral Tribe that epitomised the outlaw spirit of rave culture, to the perfect 21st century techno sound of havens like Berghain and Trouw. The technology of sound has informed the culture and vice versa throughout the modern age.

What “great sound” is, though, is tough to define. What makes good sound is not a simple science. The study of acoustics is beset by complexities of turbulence and interference patterns – and the art of filling an irregularly shaped room full of moving bodies with sound that will satisfy on an aesthetic and physical level has sent many great minds round the bend over the years.

And it’s not just about sound either, because the soundsystems themselves have a mythic quality. They are the beating heart of the layout and décor of clubs, parties, festivals and dances. The glib old adage of “dancing about architecture” doesn’t seem quite so silly when you are moving to and through the air pushed out from a legendary system.

Mikey Dread, creator of and selector for London’s venerable Channel One Sound System, talks of sound fanatics coming to watch the rig being set up each year at Notting Hill Carnival as “like tourists coming to see Stonehenge”. He means it jokingly, as if to say it’s something people like to tick off on their holiday itinerary, but he actually hits on something profound: the speaker stacks are in a very literal sense monumental – “majestic and authentic” as Positive Sounds‘s Darren Kis puts it – and maybe even ritual in their function.

It’s not just the battered wood and Hailie Selassie posters of classic roots and dub setups like Channel One that have this power. Think of something like Positive Sounds’ iconic white speakers with black stars which have loomed over a quarter of a century of free parties and can be seen in film of the legendary 1994 Criminal Justice Act demos; of the futurist design of Japan’s Broad Axe. Or look further towards the terrifyingly expensive high-end interior design of Spiritland; and, of course, of the cyberpunk geometry and purple boxes of Funktion-One – which became possibly the most potent visual symbol of the 2000s bass generation. The look of these creations sets the mood for the dance, creates the space in which we move, and primes us for the musical experience.

“We live in an age where speakerbox innovation is everywhere.”

We live in an age where speakerbox innovation is everywhere, from the vast war-machine festival rigs of EDM hell, through hip hop lovers’ booming car systems, to Minirigs and the huge array of Bluetooth gizmos that will practically put a party in your pocket. The ways in which territory and our sense of our own existence in physical space are defined and delineated by the soundfields of our technology is increasingly the story of our social world (see Steve Goodman aka Kode9’s book Sonic Warfare for a rollercoaster ride through this topic).

And in underground music the importance of the speaker stacks is as great as it has ever been: from that omnipresent Funktion-One iconography through nostalgia for Plastic People, to the pilgrimages people make to Berghain’s literal wall of sound; the rigs are every bit as woven into our culture as are the venues, drugs and music itself.

This is not lost on those who create the soundsystems. If asked about their rigs, the usual first response is “it’s all about the sound”, but push them and you’ll generally find there is a deeply thought-out, refined and individualist sense of the appearance and placing of the boxes, speaker cones and electronics. Quoc, the proprietor of Dub Stuy soundsystem in New York, says: “The system stands nearly 10ft tall and about 8ft wide so it’s a pretty imposing object when you stand in front of it. Most people are in awe when they see it for the first time, given its size and striking look. It’s usually the first thing you notice when coming into one of our events. I’d like to think of my system as being the star of the show, and I want it to be the central part of the performance.”

Or take VIVEK – whose System Sound has been instrumental in preserving and pushing forward the values of OG dubstep – who says: “It’s very different from your normal club surrounding. The physical aspect of the soundsystem is far more important than the aesthetics of it. Up close, the speakers have taken a battering, but in a darkened room, two walls of sound look beautifully intimidating. The music I play is very physical so the physicality of the soundsystem compliments the music.”

“At its best, soundsystem culture is multimedia art in the truest sense: a synergistic totality of sonic, visual, physical and mental experience.”

System is a perfect example of how the speakers define the dance. For a long time, the dances were held in the Dome in Tufnell Park, one of London’s less glamorous venues with the feel of a church hall or working men’s club, with no lighting rig, no lasers or projections, just decks on a table and the system itself to create the atmosphere. The room is transformed by the the installation of the system, whether permanent or just for the night.

As Jerome Joly of Glasgwegian system Mungo’s Hi-Fi puts it: “It adds to the vibe by creating an arena where people are surrounded by DJs, MCs, crew, stacks of speakers as well as the sound. A sound system is not just a PA, it’s part of the show, the decor and the experience of the traditional reggae dance.”

At its best, soundsystem culture is multimedia art in the truest sense: a synergistic totality of sonic, visual, physical and mental experience. The sound and the look of the system cease to be separate elements and become intertwined for the dancer/listener. As Paul Noble, manager of the high-end Spiritland rig says: “the synergy between the space, the system and the people make for something magical”.

Andrew Morphous of the Tsunami Bass crew in New York reiterates: “Visually, the full rig is stunning in its various configurations. Monolithic is a word that often comes to mind. But the form is in the functionality and it is the feeling of that live experience with each and every frequency resonating inside and out that is what its all about. The aesthetic is secondary to the art of the science of enabling that golden spiral effect that lends deeper dimensionality to the music being presented. Its a shame when bass culture is poorly curated and can’t be felt properly. A disservice to the genre.”

The inspiration for the look of the systems can come from the most unlikely places. The people who build them seem often to have visionary tendencies, and though the wiring and placement might seem scientific and logical, it is also an art. “How’s it make me feel to be near it and look at it?” muses Kintaro Owada, who built the Broad Axe soundsystem that powers the Back To Chill dances in Tokyo. “Hmm… I suppose I love the balance of it. I think it looks like a gundam or mecha [the giant piloted robots that recur through Japanese mangas and animes]. But very differently from that… around when I was just starting, I saw a movie where in the school garden there was a big Chinese character for ‘freedom,’ and I feel that the sound system is most important when I associate it with that character. I’m not sure I even separate the look and sound, but I conceive of it as a work of functional beauty.”

“I like to compare sound systems to totems, they tower high over the crowd, commending respect and admiration.”

Likewise, Dub Stuy’s Quoc went into the creation of the system with a vision that is unashamedly romantic. “I like to compare sound systems to totems,” he says. “They tower high over the crowd, commending respect and admiration. A proper sound system experience can be quite spiritual, quasi religious even. As a sound system crew, the visual aspect of the system is an inherent part of our identity and image. It’s very important to us as it enables to distinguish ourselves from other sound systems. There’s always been an element of competition in our community and having the a visually unique system plays into that aspect.”

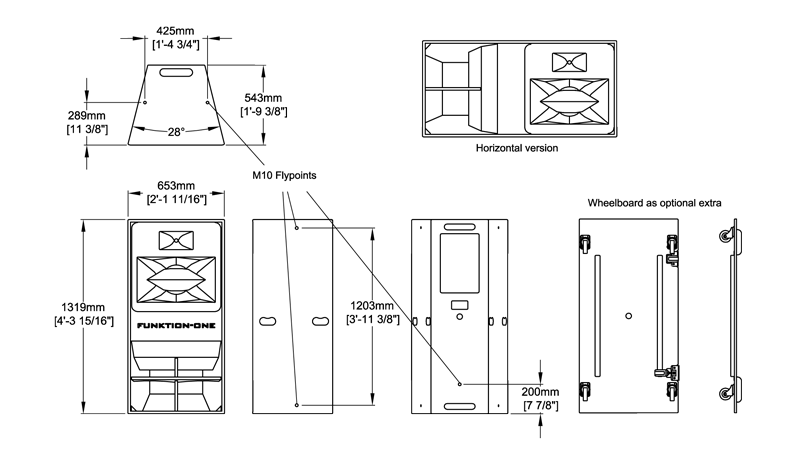

Funktion-One’s inventor Tony Andrews is something of an old hippie. His earliest inspirations in soundsystem building were 30” cones he saw back in the 60s. It doesn’t take much to get him talking about cosmic inspirations for his particular theories of sound, and the purple hue of many of his company’s products comes directly from his visions on first hearing Jimi Hendrix’s “Purple Haze” (and because “I’m not keen on black, which everything else usually seems to default to”). The “axe head” speakers that make Funktion-One stacks so recognisable had a surprisingly warlike inspiration.

“Form follows function,” he says, “just as much as if you’re making a windsurf board where the sail and the board have very particular shapes and sizes because of the different resistance and viscosity of air and water. We didn’t learn to make planes until someone looked at a seagull and understood why the cross-section of its wing was like that. And funnily, some of those angular lines on the axe head came from when we were exposed to the Stealth Bombers during the first Gulf War. All those angular shapes designed to deflect and scatter radar – that gave us inspiration about how to deflect all the sound frequencies to spread evenly so it’s not all focused in one place. You can take inspiration from anywhere.”

Sometimes, though, it’s less about mystical or scientific inspiration and purely about making an impact. Positive Sounds was originally called, in self-explanatory fashion, The Purple Polka Dot system. “It literally was a massive eight scoop set-up painted white with purple polka dots all over it,” says founder Darren Kis; “my reasoning being that ravers would remember it. When that came to an end in 1990 and Positive rose out of the ashes the following year I just painted over the purple spots and kept the boxes white.”

Those white boxes with black stars stencilled over the bass cones’ grills were just as memorable as their gaudier predecessor. It made Positive one of the most recognisable setups of the 90s free party era, and served as a beacon to party people traversing the countryside of southern England.

Though soundsystem builders and curators can be romantics, there are always some who are pragmatic tech heads.

Sometimes, though, it really is just about the sound. Though soundsystem builders and curators can be romantics, there are always some who are pragmatic tech heads. “I think of my set up as being purely functional,” says Sam XL of LA’s Pure Filth; “and I’ve seen a lot of systems that look nice and pretty but sound like shit. Remember, just because it looks like a Ferrari doesn’t mean it really is, check under the hood. A top tier rig running off cheap amps without the correct processing is gonna look great and sound like shit after a couple of hours, kinda like a Ferrari with a Volkswagen Beetle engine in it.

“I’m an old school raver, so I want my rig to sound just as good at eight in the morning as it did at ten at night when we started. Running full tilt in 100º plus weather at Coachella for 14 hours a day, three days straight with artists like Andy C, Ras G, Kode 9 etc rinsing the hell out of it. That will let you know really quickly about the strength of your rig.”

At the other end of the scale is Spiritland – a half-a-million-pound hi-fi, the kind of thing only the 1% can afford for their homes, but built for public consumption: it may be clad in luxurious wood, but sound is its priority just as much as it is for the more rough and rugged Pure Filth. Paul Noble says: “It isn’t a club system, and doesn’t really deal in brute power, it’s about clarity, emotion, and a delicate musicality that works across several genres and moods.” But even if sound is the only priority – whether that’s about brute power and functionality or “delicate musicality” – a soundsystem will always remain a visually fascinating totem, part of the show, and one of the grandest of human achievements.

To give the last word to probably the most famous soundsystem designer of our times, Funktion-One’s Tony Andrews: “Saying that sound is paramount doesn’t mean form is irrelevant as such, we appreciate the look of these things. We all like the look of fast cars, and streamlined things that are meant to cut through the air, jet aircraft, things like that. They have a look because of what they’ve got to do, and that look becomes part of our aesthetics. Even more so if you start thinking of the forms that have come from function in nature, the adaptations, the things that evolved. The way natural things look is fascinating to us, but it all comes from function.”