“If these motherfuckers can deliver again then they’re the truth.”

It was one of those moments that could only happen in Atlanta. I was 15, and it was a school night. To be exact, it was Monday, October 30, 2000, at 11:30pm. Outside, the now-defunct Earwax Records shop on Peachtree Street in Midtown, a line stretched down the block from the store’s entrance. There was a slight chill in the air, accompanied by an occasional wind gust, and loudspeakers playing “B.O.B.” and “Ms. Jackson” on loop. My two friends and I were well past our allotted weekday curfew times, but didn’t care or even think about the impending punishments that would be handed down for our sins. Being grounded for a week – a month even – was totally worth it when we reminded ourselves of the reason we braved the elements in the first place.

In 30 minutes from that point, Andre “3000” Benjamin and Antwan “Big Boi” Patton, along with the rest of the Dungeon Family would enter through Earwax’s back entrance. Inside, the two would sit at a table — Andre, his hair straightened, rocking a tie-dye shirt and head band, and Big Boi, his partner-in-rhyme, appearing more cozy than ever in a light blue Coogi sweater and fur, all-white Kangol hat — Sharpies in hand, gave daps and pounds, maybe even hugged a few babies. Most importantly, they signed copies of their fourth studio album, Stankonia. That night I got home, I immediately popped the album into my Sony Discman and didn’t sleep for the next few hours.

After years of sleeping on the South, the then-institution, The Source magazine, blessed Aquemini with its coveted 5 Mics rating, deeming it a hip hop classic. Due to the track record of its creators, Stankonia would have been seen as a failure if it didn’t live up to its predecessor’s level of critical acclaim.

“Everything was on their shoulders,” Earwax Records owner Jasz Smith would tell me years later. “Stankonia was that one that people thought if these motherfuckers can deliver again then they’re the truth.” Though the OutKast track record preceding the album was stellar, thanks to the not-so-kind reviews of Goodie Mob’s World Party, there was a sense that the Dungeon Family’s flagship artists had to succeed. “These two young brothers personified all of our dreams, hopes and aspirations,” Ray Murray said in an interview at Stankonia Studios in 2010. “We put everything we had as a collective into that and the manifestation of that is what you see now, and they’re some of the biggest rap artists in the world. And they’re bigger than rap music.”

Critically and commercially, Stankonia would deliver, making mainstream stars out of Andre and Big Boi, and putting a spotlight on the rest of Dungeon Family. The two dope boys from Atlanta helped shift hip hop’s focus to the South, won the award for Best Rap Album and got a nod for Album of the Year at the Grammys, and released their most ambitious project as a duo. Sadly, it was the last album in the OutKast discography that features the collaborative production and creative spirit shared between Andre, Big Boi, and producer Mr. DJ, collectively known as Earthtone III. Stankonia simultaneously marked a new wave in hip hop and modern music, but stood as the end of the OutKast team we knew on Aquemini, ATLiens, and Southernplayalistacadillacmuzik.

What happened before the album’s release, and what followed after, is an example of artists, frustrated with their environments, reacting creatively, and inspiring others to follow suit and take chances in expressing themselves. In the process, careers and history was made, fallouts occurred, and things fell apart. OutKast, Atlanta and music in general has not been the same since.

Don’t everybody like the smell of gasoline?

Well burn muthafucka burn American dreams

Don’t everybody like the taste of apple pie?

We’ll snap for yo’ slice of life I’m tellin’ ya why

I hear that Mother Nature now’s on birth control

The coldest pimp be looking for somebody to hold

The highway up to Heaven got a crook on the toll

Youth full of fire ain’t got nowhere to go, nowhere to go

— Outkast “Gasoline Dreams”, Stankonia

On September 29 1998, OutKast released their third studio album, Aquemini. After breaking out with the G-funk leaning debut, 1994’s Southernplayalistacadillacmuzik, and taking a mental trip to outerspace with the follow-up, ATLiens, the music world wasn’t quite sure how to wrap their heads around the media-labeled “player” (Big Boi) and “poet” (Andre 3000).

“When OutKast originally came out, 8Ball & MJG was the biggest thing pumping in Atlanta. We would be in the Bay Area. We would be other places. Then, by the time we got home, Atlanta was proud,” Rico Wade said during an interview this year. “But it wasn’t like how Future or how some of these artists, now they have to blow up in Atlanta first. We really and truly was not worried about just Atlanta. (…) We was worried about New York and the West Coast. Musically, letting them know that we could get at them in New York, just believing that they good enough, that they can rap.”

On ATLiens, the duo, most notably Andre, put down the blunts and 40-ounce bottles of Olde English that fueled the group’s early creative spirit. Andre started rocking turbans, eccentric outfits, and had a baby with bohemian soul/R&B wunderkind, Erykah Badu. Though OutKast drew praise for stepping to the plate lyrically with ATLiens, two years on, Master P’s No Limit Records was the commercial king of rap music thanks to Silkk the Shocker’s Charge It 2 da Game and Master P’s MP Da Last Don. Above the Mason-Dixon Line, Big Punisher (Capital Punishment) and DMX (It’s Dark and Hell Is Hot) helped New York regain some of the swagger that died with the Notorious B.I.G. the year before.

“We knew we were fighting for the civil rights of Southern hip hop. Our attitude was strong, outspoken, articulate.”

– Cee-Lo Green

In the Dungeon Family, the collective was going through successful releases on both a major (Goodie Mob’s Still Standing) and underground (Cool Breeze’s East Points Greatest Hits and P.A.’s Straight No Chase) level. Though OutKast were credited with putting the Southern rap world, specifically ATL, on the map, the duo and the Dungeon Family’s lineage, was in line with how the collective offered something different from the mainstream train of thought.

“We come from so much history, so much heritage in our city, that we’re comfortable in our skin,” Cee-Lo Green told GQ in 2011. “We come from being Gs. There was something very focused about the spirit that surrounded us, that had been born in us and bestowed upon us. It felt like a mission, like civil service. More like activism than entertainment. We knew we were fighting for the civil rights of Southern hip hop. Our attitude was strong, outspoken, articulate.”

Organized Noize

Organized Noize

In a year when a 49-year-old black man in Texas was dragged to death, America continued being America, but OutKast and the Dungeon Family were again looking to break the mold of the duo’s two previous records and build something sonically radical, while staying true to their roots as Southern-born and -bred storytellers with cosmic aspirations anchored in red clay realities. OutKast were the budding stars but they still learned from the collective’s elder statesman.

“When we were that young, Organized Noize and Ray and Rico and Pat [Sleepy Brown], they were really kinda like big brothers, and they really guided us a lot and were super influential in everything OutKast,” Andre 3000 told NPR last year. Those various dichotomies came to a head when Aquemini, with the blues-tinged funk of “Rosa Parks” and south-meets-north lyricism of the Raekwon-assisted “Skew It On the Barb-B”, caught the attention of listeners in both sides of the Civil War. For OutKast, the album would be personal, as they felt the world, even the folks in their own backyards were putting everything about the group into question.

“Back then, there was a whole bunch of shit talking,” Big Boi once said of the inspiration behind the snarling second track, “Return of the ‘G“. “People just couldn’t understand how we were making the type of music we were making. There were a lot of attacks coming at my partner, so we wanted OutKast to be like, ‘You fuck with my homeboy, we gonna fuck you up.’ We wanted to let people know, this man doesn’t stand by himself. I mean, that’s my dog. It’s a team effort.”

“If you look at Atlanta music, it kills itself every two to three years, then it rebuilds something brand new. If you look at OutKast, essentially they do the same thing.”

– Killer Mike

Before the Internet and blogs dictated what was trending and what went viral, The New York-based Source magazine was the go-to for all things rap music. Yes, this was the same Source, where during the publication’s annual awards show in 1995, also in NYC, the crowd booed OutKast for winning the Best New Artist category simply because they weren’t from one of the five boroughs. Hell, even New Jersey, thanks in part to the likes of Redman, got more musical cred than Atlanta. All of that changed with the presence of Wu-Tang legend Raekwon, and the corresponding review from the media outlet that had never heaped perfect praise on a Southern rap act in its decade-long run of being the so-called “hip hop Bible.”

“Aquemini is a brilliant record,” the review stated. “Let that unequivocal statement be said right off the bat. It possesses an uncanny blend of sonic beauty, poignant lyricism and spirituality that compels without commanding. (…) By continuing their submersion into the baptismal waters of the African-American musical continuum, and through their superb use of the urban narrative, OutKast has created a record that is rooted equally in both the long-standing tradition of the Southern-based music—blues, gospel, jazz, funk, soul, etc.—and the spirit of hip hop.”

Going into the project, the Dungeon Family collective fancied itself as a new wave Parliament Funkadelic.

By home and out-of-town standards, OutKast and Dungeon Family had their first classic (though plenty will argue the near-perfect exploits of the two records that came before it). Aquemini introduced a gang full of local live musicians that gave “Spottieottiedopaliscious” that Earth Wind & Fire vibe, or the title track its bass-guitar backdrop. The album features, aside from Raekwon, Badu and George Clinton, were comprised of artists in or with ties to Dungeon Family. Though Ray Murray, Rico Wade and Sleepy Brown added Organized Noize’s signature production to just four of the 16 tracks, Goodie Mob, Witchdoctor, Cool Breeze and Big Rube all make appearances. At 23, Andre and Big Boi were still more or less coming of age, but musically they had never been more in-sync.

Looking back on it, that’s exactly how the former viewed it. “Things were really about me and Big at the time, and I liked the way Aquemini sounded,” Andre told Atlanta’s Creative Loafing back in 2003. “It meant something really smooth, the coming together of two forces.” The two forces, along with their production partner Mr. DJ, mentors – and the rest of Dungeon Family had grown into a formidable power in hip hop. Stankonia, their next move, would arguably become the group and collective’s boldest statement.

Like Janet, Planets, Stankonia is on ya

A movin’ like Floyd commin’ straight to Florida

Lock all your windows then block the corridors

Pullin’ off on bell ’cause a whipping’s in order

I like a three piece fish before I cut your daughter

Yo quiero Taco Bell, then I hit the border

Pity PAT rappers tryin’ to get the five

I’m a microphone fiend tryin’ to stay alive

When you come to ATL boi you better not hide

cause the Dungeon Family gon’ ride, hah!

— Big Boi “B.O.B.”, Stankonia

Stankonia started and ended with the funk. Going into the project, the Dungeon Family collective fancied itself as a new wave Parliament Funkadelic. Being that musically, creatively and artistically, the crew was guided by the spirits of risk takers past, it only made sense they’d find clarity in chaos. In fact, in an interview leading up to Stankonia’s release, Andre 3000 equated embracing the funk – both as a theme on their album, and the music they were creating at the studio of the same name – to being liberated.

“I guess we’re talking about an individual freedom,” he said. “Finding that gateway that opens you up, that frees you up mentally so you won’t be stuck in a… I don’t want to say a corporate mindstate, but more like a trained mindstate. Like, you grew up a certain way. You’re used to doing something a certain way: you’re used to hearing the music a certain way, you’re used to moving, dressing, walking, talking a certain way. But when you’re trying to tap into something new, I know doing the same thing ain’t gonna get it.”

“”B.O.B.” is that shit that just recharges you; shocks the shit out of your ass.”

– Big Boi

The first evidence of the group connecting with that funk-fueled freedom came in the form of “B.O.B.”, their first single off Stankonia. Killer Mike remembers the first time he heard “B.O.B.” The MC was making most of his music in “crappy closet” studios, and was just happy to have somehow found his way into the OutKast — specifically Big Boi’s — entourage. The latter, while both men were at a strip club in Atlanta, invited Killer Mike to the studio to record a song for the group’s new album, post Aquemini. Killer Mike’s impromptu freestyle would become the single, “Snappin’ & Trappin’” and land the Adamsville rapper a spot on the corresponding Stankonia tour. His life, as he knew it, was over. However, he’d already felt a musical and cultural shift after one listen of the group’s first single.

“The first time I heard the track I just really thought this shit was not going to be the same, and it hasn’t been,” Killer Mike says. “If you look at Atlanta music, it kills itself every two to three years, then it rebuilds something brand new. If you look at OutKast, essentially they do the same thing. No OutKast has sounded like the prior OutKast, and I think as a city we have learned from OutKast, in a way, to keep creating and keep reinventing ourselves. It’s been a beautiful thing.”

In a 2010 interview, Big Boi explained the cultural climate and thought process he, Andre and Mr. DJ were experiencing at the time. “Stankonia represented a wild time for us. We were coming into 1999 and we thought the world was going to end, so we were like, ‘Fuck it… we are going all out!’ You can hear that on “B.O.B.” The first time I heard that track, it made me feel a certain way,” said Big Boi. “It’s unexplainable. The time changes in the song sent shivers through me; it made me feel invincible. “B.O.B.” is that shit that just recharges you; shocks the shit out of your ass. When that song comes on it’s like, ‘Clear!!!’.”

That state of constantly creating and challenging oneself is something Killer Mike says he learned from being around Dungeon Family. With the three previous OutKast releases, you can find clear progressions that are a fusion of Big and Dre’s creativity, pushed and fueled by the elder Dungeon Family counterparts, Organized Noize. “They took player music and polished it and put braggadocio topics with it on that first album; they evolved on the second album; and then with Aquemini they were very soulful. They had an amount of depth that nobody expected from them,” Killer Mike says.

Organized Noise were the spirit guides for “Ms. Jackson”, the song that arguably launched OutKast into the very ‘mainstream’ that they had formerly shunned on ATLiens. Andre 3000’s ode to Erykah Badu’s mother was a grownup, classy, but blunt take on something a lot of single couples go through. Think B-Roc and The Biz’s 1997 one-hit-wonder, “My My Baby Daddy”, but for a far less ratchet crowd.

After the release of “Ms. Jackson” and Stankonia’s quadruple-platinum success that followed, OutKast and Dungeon Family had crossed over into another realm of stardom. “Stankonia took the world’s greatest rap group and made them one of the world’s greatest bands,” Killer Mike says. “What I mean by that is when OutKast is 50 years old, they’re going to be able to do a 50-city, multiple country tour like the Rolling Stones.”

Killer Mike

Stankonia also marked the moment that OutKast and Earthtone III would go their separate ways. “Stankonia, it was a strong finish,” Mr. DJ told me in an interview a couple of years ago. “Everybody had a lot of input, therefore we made good songs. Everybody was at their creative max, which I think in turn caused everybody to kind of branch off and start to do their own thing, because now you have your individuality and you want to express that.”

That was more or less the theme for everyone in Dungeon Family from that point forward. Cee-Lo Green left Goodie Mob to pursue solo success, and later form Gnarls Barkley with DJ Danger Mouse. The group reunited and have since dropped 2013’s Age Against the Machine. Other first-generation Dungeon Family members such as Backbone, Sleepy Brown and Joi all released solo projects. After a few start-stops, Killer Mike (a second-generation Dungeon Family member), found his way to mainstream success with the underground rap attitude of Run the Jewels with El-P. Everyone from Slimm Calhoun and Witchdoctor put out solo efforts, but none found the success of Cee-Lo and Killer Mike. Along with Killer Mike, other second-generation Dungeon Family members such Bubba Sparxxx and Future have found mainstream success. Though, aside from any commercial or critical praise, the Dungeon Family’s roots run deeper and extend farther than a few albums.

“Of course, most crews break up or get into big arguments,” Sleepy Brown said in an interview for journalist Jeff Weiss, looking back on the Dungeon Family makeup. “Even if we did that, we’d work it out. We’re all brothers and we will disagree on stuff, but at the same time, we are family and we understand each other. I think that’s what it is, we still have a love for the music and for each other. We believe in us and believe in our name. Back in Atlanta, that’s all we had because we were trying to put Atlanta on our back.”

“They’re some of the biggest rap artists in the world. And they’re bigger than rap music.”

– Ray Murray

And others will attest to that bond spilling over into the younger generations. In 2014, at OutKast’s 20-year anniversary tour – which also functioned as a sort of Dungeon Family reunion – Janelle Monae hammered this point home. After all, it was Big Boi and Andre who took the Grammy-nominated artist under their wing. “OutKast has opened up so many doors, not just for myself, but artists of color. They basically rewrote how hip hop could sound, what it could look like, how we could dress, the things we could say, the live instrumentation in music,” Monae said in an interview. “They were the most innovated in my opinion. The whole Dungeon Family; they’ve been an inspiration to me and my arts collective, Wondaland Society.”

This sentiment echoes Killer Mike’s thoughts exactly. “If you look at Atlanta you see a huge Dungeon Family influence now, whether you’re talking about the eccentric way that Atlanta artists dress, the way they embrace their own. Future raps the way the Atlanta people talk and he’s not ashamed of that. That comes out of the OutKast lineage and Dungeon Family/Goodie Mob experience. If you look at Young Thug, he dresses and expresses his way through clothes in way where he doesn’t care about your judgement, that comes directly out of the OutKast experience,” Killer Mike says.

“No one was walking around proud to wear flip flops and socks when Goodie Mob did that. Nobody was running around at the same time on some hood shit spitting esoteric shit about the universe, until you heard Big Rube and Dungeon Family. So for me, Dungeon Family has not only shaped Atlanta; it helped shaped the South. No Dungeon Family — no Killer Mike, no Future. No Dungeon Family — no Raury, no Young Thug. No Dungeon Family – there’s no Atlanta scene feeling comfortable to reinvent itself over and over again.”

The game changes everyday so obsolete is the fist and marches

Speeches only reaches those who already know about it

This is how we go about it

– Andre 3000 “Humble Mumble“, Stankonia

Today, hip hop is full of collectives (Two-9, Odd Future, Awful Records) that likely wouldn’t exist if it weren’t for the Dungeon Family. The eccentric genius — Kendrick Lamar, Frank Ocean, Tyler, the Creator, Lil Wayne — all took cues from the Andre 3000s and Cee-Los that came before them. If anything, the Dungeon Family, via OutKast and genre-defying, risk-taking projects such as Stankonia were audiovisual representations of embracing creative freedom. These days, Big Boi has been steadily releasing exceptional solo efforts (Sir Lucious Leftfoot: The Son of Chico Dusty and Vicious Lies & Dangerous Rumors), and experimental collaborations (Big Grams with Phantogram), while Andre is sporadically guest starring on tracks, doing the occasional film and randomly showing up at concerts around the country – and strip clubs in Atlanta.

Big Boi is arguably keeping the musical spirit of OutKast and Dungeon Family alive and well — with Future and Killer Mike holding their own as well — but the collective and its stamp on hip-hop culture was never marked by the sheer quantity of their releases, and financial gains. That’s probably best found in the Stankonia Studio they purchased back in 1998 from the IRS by way of Bobby Brown. Stankonia was made there, and everyone in the next wave of ATL musicians have recorded in the space.

If Atlanta music is reinventing itself every few years, chances are that reinvention is happening in the legendary recording rooms at Stankonia. Andre 3000 referred to the studio as “the place from which all funky things come.” For Mr. DJ, who still spends every day at the building, currently working with Big Boi’s protégé Malcupnext, the name itself carries the weight of the entire Dungeon Family and OutKast legacy.

If Atlanta music is reinventing itself every few years, chances are that reinvention is happening in the legendary recording rooms at Stankonia. Andre 3000 referred to the studio as “the place from which all funky things come.” For Mr. DJ, who still spends every day at the building, currently working with Big Boi’s protégé Malcupnext, the name itself carries the weight of the entire Dungeon Family and OutKast legacy.

As he once told me, “Stankonia and the name: it’s a symbol of Atlanta because we were the first ones to claim Atlanta and make Atlanta be respected on a larger scale. Before that, you had Jermaine Dupri that was here. Kris Kross – rest in peace to Chris, love those guys – represented a kind of Naughty By Nature New York style. Da Brat was representing West Coast style, so nobody was really representing Atlanta ’til we did. Stankonia symbolizes that.”

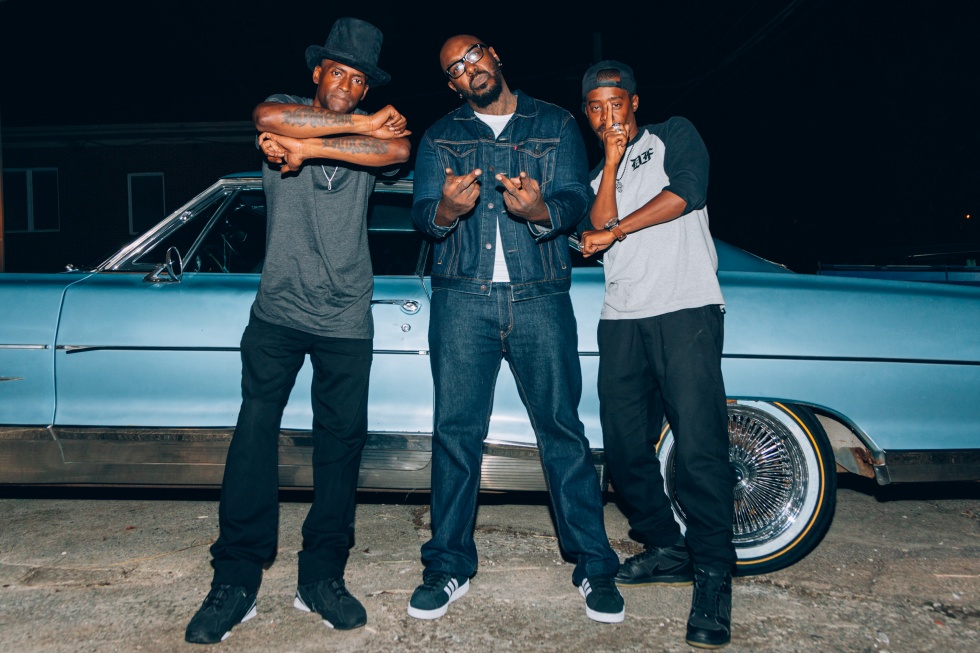

The Art of Organized Noize exhibition, Elevate Public Arts Festival

In October, the City of Atlanta celebrated their annual public arts event, Elevate. Curated by visual artist Fahamu Pecou, with a theme of “Forever I Love Atlanta (F.I.L.A.),” one of the centerpieces of the cultural affair is an art exhibition called The Art of Organized Noize. The exhibition features relics lifted from the original Dungeon, as well as gold and platinum plaques, and the eye-popping costumes and outfits worn by members on stage and in videos. Like OutKast, and Dungeon Family, Elevate’s goal has always been to put a spotlight on those generating creative energy in Atlanta, and promoting that art. Though, as a collective, Dungeon Family hasn’t released a proper album since the much slept-on Even in Darkness, their hold on the city and the world is still felt today.

At an Elevate press conference, Pecou was flanked by Ray Murray, Rico Wade, Atlanta City Councilman Kwanza Hall and City Council President Ceaser Mitchell. Wade told the media in attendance that, no matter where the family members are in their careers or life, “the Dungeon is wherever we are.” He took the notion back further to his Dungeon Family’s early aughts of pushing the youth to channel their artistic selves, and how that’s being realized with Elevate’s embracing of Organized Noize. “What we did in the 90s as far as bringing the arts to Atlanta and making kids in Atlanta appreciate their talent and what they could do, this is equally important,” Wade said. “It’s different levels of the arts [and] the more forms of creative expression you have, the more balanced you are as a human being.”

Two kids who took that message to heart back in 1993 were Big Boi and Andre 3000. Under the guidance of Organized Noize and in the presence of the entire Dungeon Family, two boys grew to be one of the greatest duos in music history. In the process, their collective — mentors and protégés alike — challenged our very notions of being creative, artistic, and having the willingness to go against the grain in spite of what the general buying public thinks. If they were over your heads, it’s OK. You will catch on later. Though OutKast had diamond discs and Grammy-awarded success with Speakerboxxx/The Love Below and major motion picture and soundtrack of the same name (Idlewild), it can be said they were at their creative peak, as a group, with Stankonia. The album, like the artists that created it, was inspired by individuals, egging each other on to find and embody the spirit of creative independence.

OutKast was guided by the experiences of being in the Dungeon Family, which started and doesn’t end without a say from Organized Noize. What was once thought to be something that could happen only inside Atlanta’s famed Perimeter, traveled around the world and back. On “Humble Mumble” off Stankonia, Big Boi raps, “You want to reach the nation / Nigga, start from your corner.”

Fifteen years after Stankonia’s release, we still hear OutKast and Dungeon Family’s message loud and clear.

Watch Organized Noize dissect their classics.

All photos: © Elliot Liss, 2015