Anyone who believes that quality, innovative club music needs to be a niche concern should really take a look at South Africa. For all the struggles that the nation has gone through as it grows and finds its identity post-Apartheid, it has always been a musical powerhouse – with high quality club music selling in quantities that would turn most European or American producers green with envy, and which continually evolves, incorporating local styles and languages as well as influences from outside.

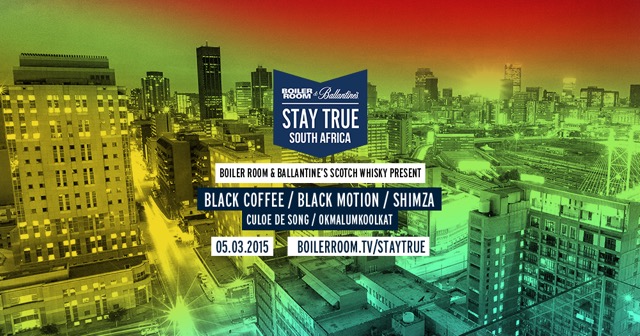

For the next in our Stay True series of documentaries and shows with Ballantine’s Scotch Whisky – which aim to find stories worth celebrating in the most exciting music scenes worldwide – we are heading to South Africa to find out exactly how this incredible and unique music scene works on the ground.

Among the lineup for our S.A. show is Smiso Zwane aka Okmalumkoolkat – a musician who’ll be known to Boiler Room viewers for his work with L.V. on Hyperdub, and more recently for his killer EP on Australian label Affine, but who has a whole other musical life in South Africa, and has plenty to tell us about the opportunities and challenges that his homeland presents.

JOE MUGGS: How you feeling about the Boiler Room x Ballantine’s Stay True show?

OKMALUMKOOLKAT: I’m really excited about this, I didn’t imagine I’d be doing a Boiler Room this year, so it’s super exciting for me.

And is there anything else in particular on the bill you’ll be checking?

Oh I’m down to check anyone – my friends, people I’m not really familiar with, whoever. I’m that kind of guy that I play my show then watch all the other shows, or just join the party, you know? I don’t like the VIP!

We know you for your stuff on Hyperdub, and now Affine – but you have big tracks in South Africa that haven’t crossed over here. Does it sometimes feel like two separate careers?

Heh, yes it’s getting to that. Before I was in denial, now it’s actually getting to that point so there’s the stuff I’m doing for overseas and the other stuff that really rocks, but when I do it overseas it doesn’t really hit. So yeah it’s like there are two people now…

What in particular works in S.A. but not elsewhere?

Right now, because we’re quite a young nation, we only got our independence in 1994, we’re still trying to find ourselves in a sense. And right now we’re going through a resurgence of kwaito; we had a lot of kwaito in the nineties, but what I started doing with [his band] Dirty Paraffin is becoming known as “new age kwaito” in South Africa and everyone is getting on it. In a way it’s going backwards for me – when we first started doing it with Dirty Paraffin nobody was getting it but now everyone gets it – but there’s no use me not doing that stuff as well now, I mean I can still do the futuristic stuff too. Otherwise I’ll always be irrelevant.

So does “new age kwaito” strictly re-tread old rhythms, or are there new elements?

Well what I try to do with my crew is take it a step further, but a lot of people are just remixing the old stuff. But the kids who are listening to our stuff are kids who were born in the nineties or after so they have a little bit of kwaito in them, but they don’t really know – so everything is exciting to them, and that means people are getting a bit carried away with it. “Oh the kids are loving it, so I just need to keep on doing more and more of this old style,” you know?

Well I guess there’s a parallel to tracks here in the UK that sound identical to really old-school house – but to young kids that sound is totally new.

Yeah, it’s quite a crazy thing. I think these kids are ready for future music also, but it’s cool to go “yo, there was this cool thing that you guys missed out on, check it out” and if they love it even better… but like I say, I think we get a little stuck on that, and we shouldn’t. I think we should take all this stuff a step further.

What are the styles that most influence you at the moment?

Well I met Batida in Berlin in November, and he gave me a lot of stuff from Lisbon, stuff from Angola. I’m really digging the stuff from Angola and Tanzania, and a bit of hip hop from Ghana. House music from here, too, because I’m friends with all the guys who make the cool tribal stuff, and the Black Coffee kind of vibes, and the qgom music from back home in Durban, which is like really hectic.

House music his still huge in S.A. right?

It’s the biggest thing. The biggest.

I remember speaking to a Belgian friend who runs the Room With A View label, cool jazzy deep stuff, and he actually gets paid royalties from bootleg mix CD distributors in S.A. – it blew my mind that it’s so big that even illegal channels pay artists.

Yeah yeah man, definitely. In South Africa compared to the rest of the world, the difference is we get to play house music on the radio. You’ll have a house track be the best, biggest track of the year. On New Year’s Eve, it’ll be a house track that everyone requests as the track of the year. On the charts a house track will be number one. You listen to the radio and straight after the chart show, there’ll be a guy actually mixing house music for three hours. I’ve been to Europe and I’ve never heard real dance music on the radio in the day, but here it’s a staple – people have been normal with that right from the nineties. It’s not a big deal, it’s a part of life. I grew up listening to house music, all my teen memories are based around DJ Fresh compilations, those compilations are all there in my memory box, I can’t take that away. If you play any track from those compilations I’ll cry sometimes.

Is that true across the racial and class divides that still exist in South Africa? Do people mingle as a result of this music being so universal?

Mmm, a little bit – not as much as it should be, though. An example is Black Coffee – he is probably the best known DJ in South Africa right now, and I think Black Coffee could play anywhere right now, that’s probably been true for the last two years. But it shouldn’t have taken that long, and there’s hardly anybody else like that. In South Africa you could go to the same club, maybe on Friday it’s more a black-dominated party, on Saturday it’ll be a white-dominated party, and they’re totally different: maybe on the Saturday they’ll be playing real 130bpm super EDM sounds and the vibe is totally different. What’s crazy about that is that when you go to that party on Saturday, they’ll call it “deep house” which is so so different to our deep house. It’s a lot of stuff to get through I think, in terms of getting people to just love the music, and follow a DJ without caring what colour he is.

So if there’s one message about South African music you’d like to get over to people who watch our show and documentary, what would it be?

I think what people should understand is that the purpose of making music here is because people want to dance. At the end of the day, you can say anything you want on your record, it could be a love record or a political record but we just want to dance while you’re singing about your lovelife or your problems. It’s a dancing nation.

Find out more about our exploration of South Africa via the session page here.