Let’s imagine culture as a literal object. Let’s imagine that we can view it from a distance. What we’d see, let’s say, is a pyramid. The top third contains the original content generators: musicians, painters, film makers and their acolytes. Nestled below them are the early adopters of the creator’s creations: the people who immediately realise the potential of someone else’s output. Holding that system – product followed by initial dissemination – up is the rest of us: the heaving mass. We’re left to latch onto that which has already vanished into the ether. We clutch at shadows.

Lets think more specifically. Lets think about how our pyramidal system works in relation to something actual, something that’s already happened, something that we’re able to view with the sadness of hindsight. Lets think about bassline.

FIRST LAYER: ORIGIN/GENESIS

Now, you’re on the Boiler Room site. If you’ve come here directly I’m going to assume that you don’t need to be told about speed garage and Niche and 4×4. Scroll down.

If you’ve arrived here by other means: bassline is the name given to a uniquely Northern combination of house, garage, and R&B. It married the hulking, snaking sub-bass of UK Garage to the martial stiffness of house’s techier depths and hard house’s Northern bounce. It was vocal heavy club music, club music with ruffneck sense of sensuality. Germinating, roughly, in accordance with grime and dubstep, it had a femininity that the London sounds were lacking. The Todd Edwards-indebted vocal cut ups often presented the listener, and more importantly the dancer, with something akin to love songs. These were songs of romance played on heaving dancefloors. It was bright, bold, brash and unabashedly British, more Yorkshire bleep than Bmore club.

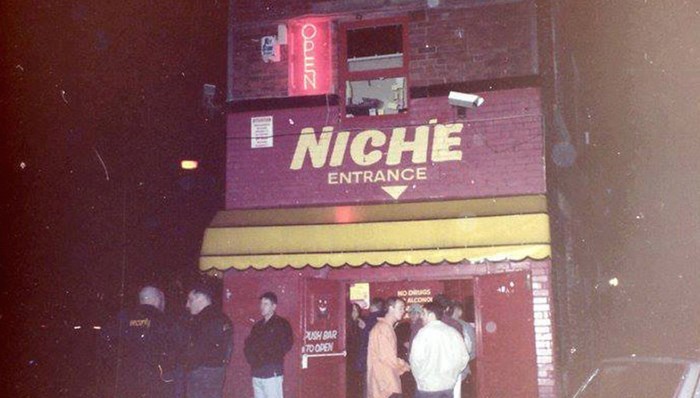

It’s other name stemmed from the one of the key club clubs of the bassline scene: Niche. The Sheffield venue thinks of itself, and is often thought of, as the genre’s spiritual home. As likely to get up and comers behind the decks as established names, it proved fertile ground for the fast moving movement. It was a place that wobbled all too briefly: the Operation Repatriation raid conducted in 2005 saw the original Niche close. Niche became Club Vibe – same tunes, different name. Then Club Vibe got the chance to extend their premises. It became Niche again.

It wasn’t purely Steel City phenomenon, however. An unlikely site of pilgrimage was the town of Dewsbury. Sat between Huddersfield and Wakefield, Dewsbury, home of Betty Boothroyd and Baroness Warsai, was home to Sheridan’s, bassline’s second club. Northern Line Records boss Paleface, speaking to Rinse ahead of his bassline-heavy contribution to the mix CD series remembered it thus: “They’ve got this big arsed… it’s like an industrial estate and this big arsed, massive long… cowshed!! And you go in there, and it’s covered in shit. You go down past the bar, and then down the corridor, and they’ve got this MASSIVE room. NO lights, it’s all dark. That was the venue for bassline.”

It may have looked like a cowshed, but what a cowshed it was.

These, and other less mythologised, clubs were fertile ground for MSN-swapped tunes that smashed the rave for a night and were immediately replaced by new one-off conquests. DJs came and went. It was a scene imbued with energy, vitality, life.

SECOND LAYER: INITIAL REPORTAGE

Club scenes – and bassline, for all the pleasure we accrue from sitting in with DJ Q [dep ed: pictured above in less (or perhaps more?) illustrious times] mixes, as much unadulterated joy as there’s to be found in a night spent sifting through Jamie Duggan sets on Soundcloud, was undoubtedly club music – get picked up on, get turned into articles like this, written by people like me who’ve never been to Dewsbury, become the subject of retrospective documentaries made by people who never set foot in Niche. With that, two things happen. Firstly control is wrestled away from the originators and they essentially become a passive part of someone else’s narrative. Secondly, the documentarians become custodians of something that they’ve, in some way, killed. A living culture becomes a museum piece.

Bassline, to all extents and purposes, ossified in 2008. Ministry of Sound, a club that now seemingly only exists to peddle stocking filler compilations, gave Niche founder Steve Baxendale free reign to assemble the first commercially minded, commercially released bassline compilation: The Sound of Bassline.

THIRD LAYER: BASSLINE IN THE CHARTS

That record – a 3CD set mixed by Duggan, Shaun ‘Banger’ Scott and Nev Wright – contains a tonne of undisputedly undeniable gold. Tracks like TS7’s “Raise Your Glasses“, “Runaway” by Danny Dubz and Davina, and “I Will Never Leave” by Zibba, Shellzy & Pee Wee are still perfect. The thing is, as with any mix CD, it records a moment in time out of time – but that’s another article. In serving it’s purpose – bringing unheralded producers to public attention – it diluted things.

What I’m finally really interested in here is the tracks on there, and from the scene at large that did cross over, the ones that shot down the motorway and into the bedroom of every teenager who had the sense to realise that those precious years are better spent in the company of outrageously plump bass rather than Conor fucking Oberst. Three of the best from a time before Route 94, when Burga Boy was bigger than Clean Bandit, when bassline, briefly, hooked a nation.

Take the biggest crossover hit bassline had, T2 ft. Jodie’s 10/10 all time classic “Heartbroken“. The average 14 year old outside of Sheridan’s catchment area wasn’t likely to process it as a bassline tune. It was just that massive record you heard, the one you could sing along to, the one that sounded as good off a phone on the back of the bus as it did on the Clubland TV live performance, as good as it did coming out of your Argos stereo. Like “Flowers” by Sweet Female Attitude, it was a genuinely perfect slice of UK club culture thats made disposability made it eternal. Its very ordinariness made it special. It has those all bassline hallmarks, those sonic signifiers – the mutated bass riding up front, the chunkily effective stomp of a skittery 4/4, that copycat thick lead line – of a Niche smasher.

Someone with more knowledge of the inside of the industry than myself could probably illuminate why a track like that finds itself as at home with Scott Mills as easily as it does Shaun Scott. Let’s leave that to them and think about another tune that snaked from Sheridan’s to your local snakebite snakepit. H “Two” O’s fucking UNREAL “What’s It Gonna Be?” is one for the ages. It sounds like being exceptionally pissed on WKD in a provincial nightclub. It sounds like every good night out ever. It’s so unashamedly a pop record, so unashamedly reaching for Top of the Pops, that is knocks you over. If “Heartbroken” was a subtle romancing of the mainstream this is full on dick pic DM stuff. It’s a brazen record. And that’s why its so perfect. It wants to be loved and knows that it will. Hear it now and you’ll want to fuck off all that self-consciously ‘dark’ techno you’ve been putzing about with in the hope that Dominick Fernow might stumble across your Soundcloud. “What’s it Gonna Be” is British dance music at its best.

Our final trip down recent memory lane is indicative of what happened to bassline after that MoS comp. Heretic as it is, I want to look at a track from…London. Delinquent’s “My Destiny” stutters and slinks with the best of the Sheffield bunch. And this, reader, is where the pyramid hovers back into view. Down here at ground level, authenticity has been replaced by the authentic-seeming. And we’re happy with that. Or at least, we know no better.

Bassline wasn’t built to last. It was too frenetic, too frantic, too boisterous and big to fit neatly in the charts. The genre’s mutation into the nebulous murk of ever-widening world of UK Bass makes sense – as Reynoldsian example of the continuum it fits. The current wave of dance crossovers that litter the increasingly unimportant top 40 are torpid in comparison to the initial explosion of Northern uproar that pounded round clubs from Halifax to Halsham. Bassline burned itself out. Let it live on in our memories. Let it erase Gorgon City and Jesse Glynn. Let’s sit every rote Soundcloud deep house producer down and drill DJ Q and MC Bonez’s “You Wot” into their skull. Bassline died in 2008. Bassline can thrive in 2015.