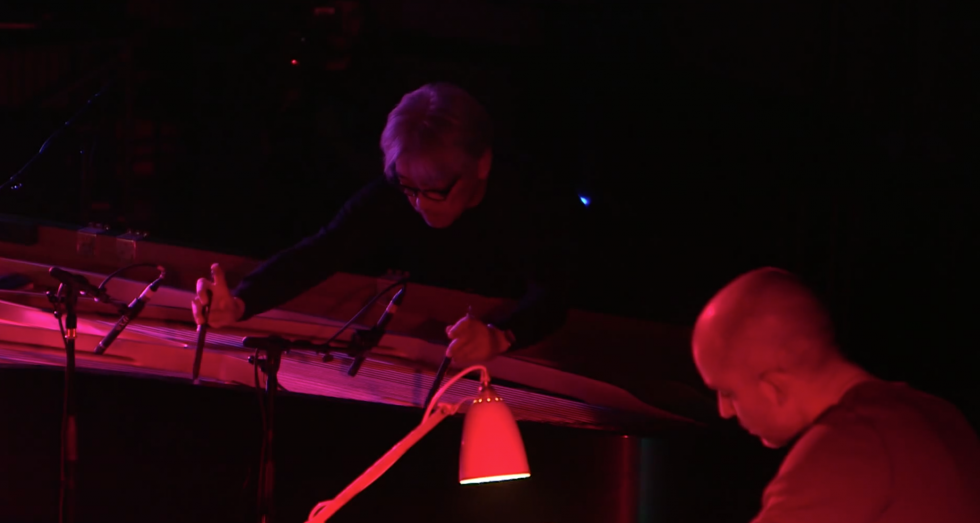

Ryuichi Sakamoto and Taylor Deupree’s live set for Boiler Room and St John’s Sessions early last year was one of the most important broadcasts in our existence so far. It proved beyond doubt to us and to our audience that BR could present the most delicate, experimental and even demanding music just as easily and convincingly as we could capture a party set from a well-known DJ.

It was also an incredibly beautiful musical experience, and the two artists’ decades-long musical trajectories seemed to perfectly intersect at this point. Sakamoto, of course, came to prominence with the still-influential electro experiments of Yellow Magic Orchestra in the late 1970s, and has gone through soundtracks (including some that became Balearic classics!) and into increasingly rarified soundscaping. Deupree emerged as a producer in late 90s techno, rave and ambient, but quickly began to escape those categories through a hugely prolific output on his own 12k label – based in rural upstate New York – and elsewhere.

Prior to the Boiler Room set, the two had worked together in various permutations since 2006, including another show in Japan in the humid summer of 2013 – this time joined by the duo of Corey Fuller and Tomoyoshi Date, aka Illuha – a recording of which has now been released on 12k as the Perpetual album. Since the Boiler Room show, Sakamoto has withdrawn from public performing due to ill health, but he and Deupree did take time to speak to us about their ongoing collaborative relationships and the nature of their craft.

JOE MUGGS: You are both prolific collaborators. Do you have a standard approach to the start of a new musical relationship, or is it different for each?

RYIUCHI SAKAMOTO: For me, it’s always easy if the collaborator has certain talents and senses.

TAYLOR DEUPREE: Collaborations are important to me exactly for the reason that each collaborator brings something new to the table. Each person teaches me different things and approaches the studio and recording differently than I do – thus expanding my own knowledge. I really prefer to work together with someone in the same studio, as opposed to working remotely via file transfer, so that’s always the basic goal and approach to starting a new collaboration.

When I collaborate in my own studio with someone else they’ll often reach for a piece of my equipment that I haven’t used in a while, or see my studio in a different way than I’m used to seeing it. This is so inspirational to me.

“I was into highly synthetic music when I started… but the only constant is change.”

Can you describe the evolution of this collaboration?

TD: Perpetual can be seen as another chapter in my relationship with Ryuichi, starting from our earlier days of email correspondence and my remixes for him. That lead to us working on an album together – Disappearance – and performing live together.

Taylor – your 12k label is now not far off two decades of existence. How close is its mission and purpose to how it was when it began?

TD: I think i’ve pretty much stuck to my original mission plan, which I’ve outlined in the “12 Principles” I published online.

The label has always really been about constant, slow change and staying small and just releasing what I’m really passionate about. The sound has changed quite a bit over the years though. If you took 1997 me, starting the label, and played Gareth Dickson and said “you’re going to release this in 15 years” I would have laughed.

I was very much into highly synthetic music when I started the label. Coming from techno and industrial music I pretty much shunned anything acoustic. But, tastes and inspirations change and how acoustic instrumentation is so important to the label. As the saying goes, the only thing constant is change, and that will continue to be one of 12k’s guiding factors.

Do you have particular memories of the Boiler Room-broadcast concert in February last year, and did anything specific change in your approach following that show?

RS: I was very inspired by the acoustics inside the chapel. i remember we were a bit worried the PA would kill or cover the natural reflections so i advised the PA engineer about that.

“The music, after all, is about listening, and listening deeply and getting lost.”

TD: I just remember the concert going over very well. I wasn’t too aware of the Boiler Room crew during the night as I was concentrating on what we needed to get done and the crew stayed, professionally, out of the way. I did get a number of compliments from friends and family who watched the live broadcast though, saying it was really well done.

How do you feel about live broadcasting of a show? Do you have a sense that a diffuse audience can be “present”?

TD: I didn’t think about that too much while it was all going on. I think I was too focused on the room and the crowd that was there. It’s hard to try to put a guess on the number of people who might be tuning into a live broadcast. Five? 30? 500? I think the fact that it’s recorded as an archive is perhaps more important.

As your music has such fine detail, what expectations do you have of an audience that is actually in the room? Do you hope for quiet, or is background noise part of the experience?

TD: At a concert like this, a formal space, a “big” show… something serious… I hope for, and expect, quiet from the audience. The music, after all, is about listening, and listening deeply and getting lost. Maybe with a small show in a gallery or laid-back more social venue some background noise would be expected or tolerated. But it’s a beautiful thing to have 1200 people stay hushed and enjoy the quiet sounds of the music.

Ryuichi, you’ve played with that sense of the barely-audible in a lot of your more recent collaborative work – with Alva Noto, with Sachiko M, and of course with Taylor. Can you say why that is?

RS: Since I started collaborating with Alva Noto, silence has been very important part of my interest, and that led me to become more interested in Morton Feldman’s music which I’ve listened to since I was a teen, along with John Cage. But I should add, my interest is not simply just in silence, but in the area where you can’t separate silence and sound. For instance, imagine the very end of a piano tone vanishing into the ambience. Why am I interested in that? I don’t know. Ambiguity? Maybe.

“Of course, some visual presentations are fantastic and integrated, but most I’ve seen aren’t.”

There’s a tendency in this recent music, especially with Cendre, the album you made with Fennesz in 2007, to achieve real tranquility even when it’s quite complicated. How do you feel when you’re making it?

RS: Thank you. Your description of Cendre is very much fitting to what I felt and feel now. It is calm. But also there are melodies and complex sounds. In fact, I just improvised my piano parts for Cendre in a day or two – it was flowing out very naturally without thinking.

“Liveness” is very important for a lot of electronic musicians now. Do you think increasing sophistication of hardware and software helps or hinders performance in general?

TD: Yes, of course I think the days of the “laptop show” are numbered, although I’m not so sure someone hunched over a bunch of other cryptic boxes is any more exciting for the audience. I think it’s just in the nature of live shows of this kind of music, often, to have a single person, not being terribly dynamic on stage. But, ultimately, that’s OK – at least for me. The most important thing is the sound, which is why I rarely perform with visuals or projections as I often feel people use them as a crutch, as a distraction, as in “OK, I know I’m sort of boring on stage so watch some TV while I play music.” Of course, some visual presentations are fantastic and integrated, but most I’ve seen aren’t.

For me it has always been important to have a sense of risk and liveness to my performances. Whether it was with a laptop or not, or acoustic instruments, whatever. I think the rising popularity of physical controllers and better integration between hardware and software is a good thing for all performing electronic musicians. It’s certainly a lot more fun.

Do you still look back to those times for inspiration, or think they’re relevant now? There certainly seems to be a resurgence not just of sounds but of attitudes from classic techno…

TD: I’m really out of touch with the techno scene. I had no idea nineties techno is making a comeback (maybe that’s good for my old band Prototype 909, though!). I really don’t work with rhythm much anymore so I can’t say I still pull inspiration from those times. However, back then I did a lot of work with overlapping time signatures. a 4/4 beat over a 5/4 beat over a 7/4 part. Those ideas interlocking and shifting loops is something I still use quite a bit today, just in a totally different way.

Do you think in such terms of categories and alignments – academic vs populist, classical vs electronic etc – and if not why not?

RS: I’ve been making music as “non-category” or “non-genre” for almost four decades. I personally listen to all kinds of music. Categories don’t mean anything to me.

TD: For me as well, genre classifications are meaningless and the press seems to invent new ones every week. I just stick to doing what comes natural to me and people can call it whatever they want.

You have increasingly dedicated yourself to the piano, though, Ryuichi; why do you think it is still such a useful machine, and hasn’t become an anachronism?

RS: Well, the piano is like an extension of my body. I always made music on the piano, but then, when I was 17 or 18, the piano became like a shackle or a fetter, because it’s mathematically manipulated according to the twelve-tone system. I wanted to get away from the twelve-tone prison. A long time passed since then. Now it is much more fun to use the piano again because it’s built with so many parts and materials such as wood boards, metal panels, metal bolts, and so on, so I can make a variety of noises by hitting and scratching those parts, not only pushing keys.

Do either of you have recommendations for new or young musicians that are worth investigating?

RS: I’m not sure they are young but [Chinese guqin (zither) player] Wu Na and [Canadian throat singer] Tanya Tagaq.

TD: I think I can speak for both Ryuichi and I about a young girl from Tokyo named Ichiko Aoba. She isn’t brand new on the scene, especially in Japan. She has released four amazing albums. However, she’s relatively unknown outside of Japan. She plays acoustic guitar and sings and makes the most beautiful, honest, real, and captivating music. I’ve had the pleasure of performing with her a couple of times, recording with her, strolling and dining with her. Ryuichi has also worked with her on a number of occasions and there’s a lot of us behind her and supporting what she does. Because of her amazing talent, that’s really quite unreal, she came up very fast as a singer/songwriter in Tokyo, but she’s still so young and has an unbelievable amount of music in her, an unbelievable career ahead of her.