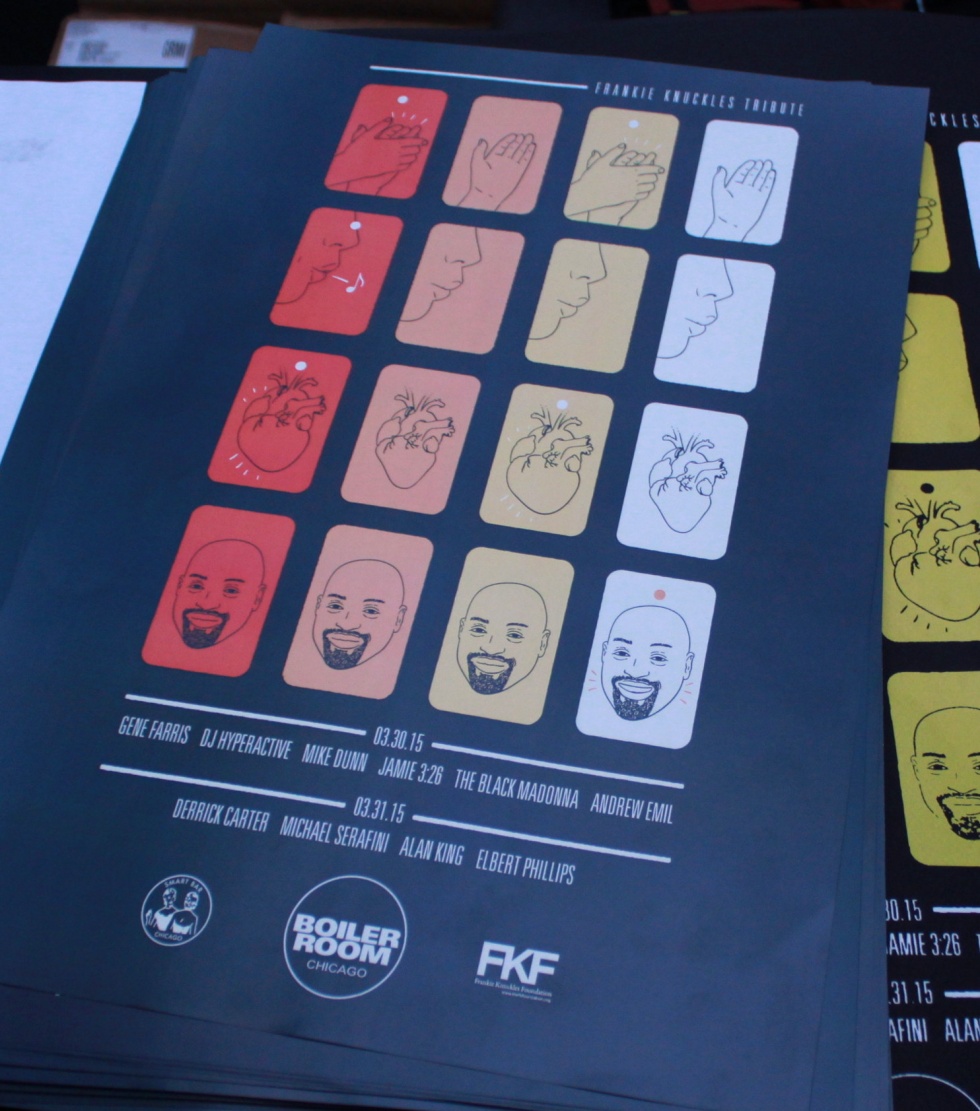

– Recordings of our Home: Celebration of Chicago Pt.I & Pt.II: Official Tribute to Frankie Knuckles shows are now live. Hit the following links for sets from Derrick Carter, Michael Serafini, Alan King, Elbert Phillips, Gene Farris, Mike Dunn, DJ Hyperactive, Jamie 3:26, The Black Madonna and Andrew Emil –

– – –

Our trip to Chicago at the end of March was an historical occasion for us. First and foremost, it was a chance to commemorate one of the founding fathers of house music, working closely with Frankie Knuckles’s friends and estate to create a pair of events that would do justice to the memory and living legacy of one of the most important musicians of the modern world.

But when we got out there, we realised it was about so much more as well. Our [then] Deputy Editor Gabriel Szatan was part of the team that was on the ground for the events, and as he spoke to DJs, producers and promoters from across the generations, he realised that he was coming face-to-face with an untold, unfinished history. Of course we’re aware that house music began in Chicago, and that as it took over the world, many of its pioneers were left by the wayside: but how that affected the city and its culture is another story altogether.

What follows is a deep tale of some of the very best club music ever made – but also about how that music is interwoven with generational, social and racial politics, with frustration and hope, and with the very specific reality of some amazing individuals’ lives. With a cast of big and bold characters who deserve to be heard worldwide, and implications for the entire multi-million global dance music industry, it is, in fact, one of the most important cultural stories you could read this year. -– Joe Muggs, former Editor-in-Chief.

– – –

Before kicking off proper, let’s get the obvious out the way. As a white, straight, milquetoast 23-year-old Brit, I’m admittedly not exactly the most natural spokesperson for a style of music that took flight out of a predominantly black, gay, expressive community. I mean, this is a culture that not only predates me, but was an established global force and had even lost some of its forerunners to misadventure by the time I was vaguely aware of my surroundings. So no, the irony’s not lost. But while on the ground in Chicago, a compulsion took hold. Everyone I met out there was sweet, selfless, genial, generous, accommodating – and agitated. There was something underneath the surface, an itch palpably needing to be scratched.

People in the city really, really, really care about house. Even as someone surrounded by music buffs of all stripes on a daily basis, it far surpasses anything I’d experienced before. There is no binary between interest and industry; these aren’t just people following a hobby on the side, or exercising proclivities on the weekend away from ‘real world’ drudgery. It’s a lifelong and all-enveloping commitment. It genuinely can’t be understated how deep those roots run. But in speaking to just a handful of people within that scene, it became readily apparent that a cloud was hanging over the place.

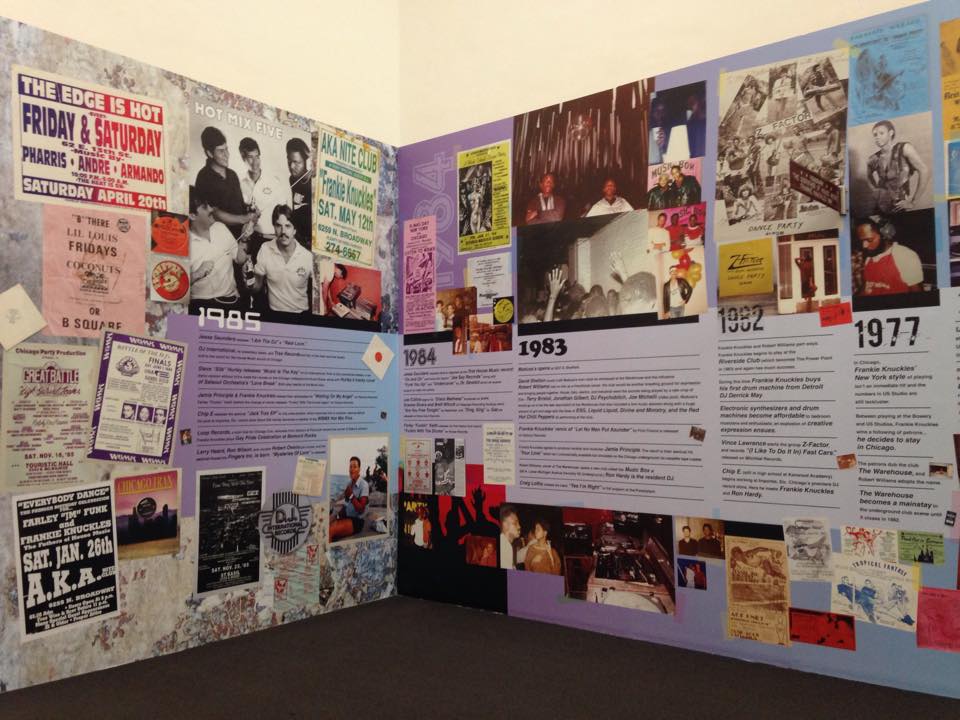

The other thing it’s hard to wrap your head around is the sheer amount of the stuff: it’s super diverse, and there’s a fucking lot of it. The highlight reel feels endless: Virgo Four, Trax, Gemini, Steve Poindexter, Chez N Trent, Relief Records, Paris Brightledge, Steve ‘Silk’ Hurley, Ralphi Rosario, Adonis, Vincent Floyd, the entire Dance Mania stable…I could go on & on. Enough quality records dropped during the first and second waves to last half a lifetime.

That’s convenient – because very little of note is coming through the pipeline now.

Chicago’s conveyor belt has by no means seized up entirely, mind you. Scope the mangled jams surfacing via the likes of Hakim Murphy and Hieroglyphic Being; the frenzy, fun and, latterly, admirable fortitude of footwork; or, obviously, an enormous hip-hop scene spanning Young Chop through Yeezus. However, within a more traditional house framework, it’s slim pickings.

Of the ten artists who participated in our two-legged broadcast, the youngest was Andrew Emil, opening up the day party at Gramaphone Records. Andrew is 34, and not even from the state of Illinois. He self-deprecatingly refers to himself as “a white guy from Kansas City,” though having migrated expressly for house, working at an audio equipment outlet across the road from the original Gramaphone by day and guiding out Rahaan’s very first release on his own label way back in ’02, dude is hardly lacking in legitimacy. Still, the point remains.

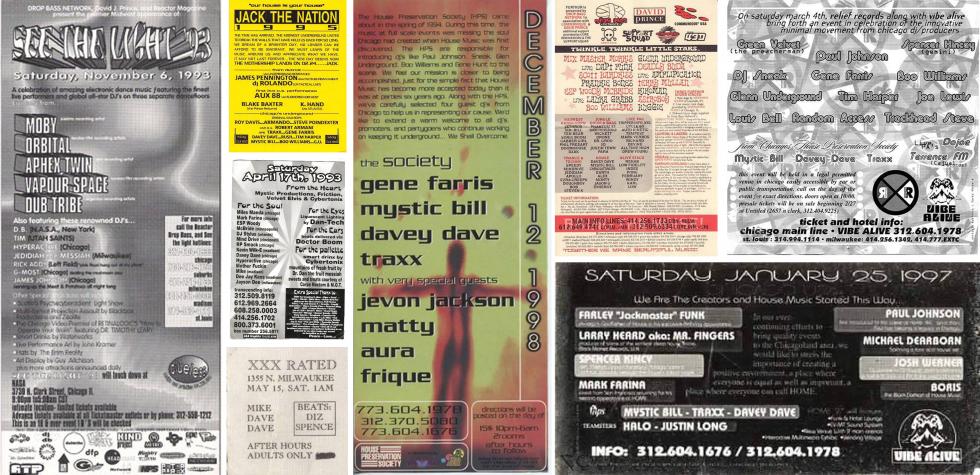

The 1990s were bookended by two notable troughs in Chicago house history. The first came a short while after the initial goldrush: a watchful eye on venues from the authorities necessitated a return back underground. Meanwhile, the Midwestern rave scene was exploding on its doorstep, fostering a fertile crossover with Detroit, the effects of which still permeate the landscape today. This was only a relatively minor skip of the needle, though, and ultimately proved beneficial, marking the second wave out as distinct from the first in the 1980s. Traxx, Gene Farris, Cajmere and many more besides cut their teeth in this environment, taking sonic cues from both the grubby warehouses and after-hours loft spaces – having rubbed up against the likes of Daft Punk, Richie Hawtin and The Orb, it’d be hard not to – leading to an altogether more varied sound.

A significantly more damaging dip came as the millennium loomed, presaging a decade where America basically put dance music back in the box. Following a half-decade run that Emil cites as producing “the most creative and coolest records in the canon,” an abrupt disjoint occurred. The likes of DJ Sneak, Mark Farina, Lil Louis (& His World), Felix Da Housecat and others collectively felt they had bumped heads against a ceiling, and upped sticks for pastures new. Many of these still talk up their origins to this day, but their words fall a little flat to those who remained. “There’s always been this adage that if you want to make a big career out of doing this, and you want to do it on your terms, you have to do so in a larger market which is conducive for this culture.” Emil trots out the example of acid house being greeted like manna from heaven in Europe, while initially ignored in the States. “This isn’t anything new,” he chuckles.

Around the same time as the mini-exodus, less commercial but no less vital talents like Boo Williams, DJ Skull and Glenn Underground largely faded from view. Civic authorities clamped down excessively hard on nightlife, imposing ridiculously overblown fines that made the earlier screw-tightening look like an act of mercy by comparison. “Things kind of fizzled out here for a while,” and while the club circuit has latterly rebounded, from an artistic perspective, the break in the chain is glaring. A third generation simply never turned up – and bizarrely, no-one’s particularly asking after where it went.

Why would they, when both the first and second still dominate the landscape?

“Chicago is very, very, very spoilt. That’s one of our main problems.”

At a punt, I’d say the most uttered word in all of Chicago is ‘Chicago’. Chicagoans have a seemingly limitless capacity for chat: a mix of proud provincialism and gutsy self-promotion that permeates most big American cities, but writ super large. It’s great. The outsize characters that litter house music further amplify this, but rather than mere chest-thumping, it’s a perpetual investment of thought in the movements and machinations going on inside their domain.

People refer to both the city, the city’s scene and the key players within that scene using a catch-all third person term of ‘Chicago’. The export of ‘Chicago’ as an international brand has furthered this mindset, which doesn’t help (or does, depending on which way you cut it). Because in every sense, ‘Chicago’ is forever trying to escape its own shadow.

Paul Johnson is one of the biggest beneficiaries of the global thirst for house music direct from the source. Over the past 20-odd years, he’s moved between Crydamoure-style filter excursions, rough ’n ready bumpers, and earworms even your aunt would recognise. Broadly unmoored from affiliation, he picks up a variety of international bookings to fit a variety of roles. As such, he’s one of the few DJs able to cast a sage eye over the state of play – and one of the few to play it straight down the line without bias. “We have a lot of egos,” and given the array of strong and often conflicting opinions, “everybody is always disappointed about something.”

(He’s not wrong: even applying the utmost care, I’m pretty confident that someone is going to take umbrage with this piece. The over-under on getting flamed doesn’t make for pretty reading.)

It’s an unfortunate paradox that a city so intrinsically tied with its creation, as both birthplace and namesake, carries such a heavy weight. The positives are readily apparent: an abundant wellspring of music and a reverential, dialled-in audience ready to plumb the depths. But as Johnson would have it, the resultant flip is that “Chicago is very, very, very spoilt. That’s one of our main problems.” Nothing’s critically wrong as such, but because everything trundles along steadily and (mostly) merrily, it has sagged and fallen miles behind on the very global stage it built from the ground up. The natural ebb and flow of most music ecosystems – tastes change; bookings wane; DJs hang up their headphones – doesn’t really occur, leaving a dense topsoil that is hard to displace.

This is exacerbated by the fact that a good clutch of house’s progenitors are still fixtures on the circuit, with first-hand experience of the glory days for comparison. Craig Loftis and Joe Smooth are two such mainstays. Loftis was so struck by his formative clubbing experiences that he went on to study sound engineering, coming round in pleasingly cyclical fashion to man the rig at The Power Plant for years; a demo reel of his “Yes I’m Right” was erroneously chalked up as a lost Ron Hardy cut a few years back. As for Joe Smooth, well: “Promised Land.”

“House music as a whole doesn’t have a temple anymore,” laments Loftis. “The Warehouse, The Music Box, The Power Plant – those places were temples where the house community came to worship. When they closed down, things got real scattered.” Smooth counters that Smart Bar, scene of Boiler Room’s second broadcast and due to celebrate its 33 1/3rd birthday in July, “has a longevity, a purity and certain spirit,” but it’s a different beast nowadays. House music, frankly, is a different beast nowadays. Over thirty years, the shifts in sound, appeal and monetisation are too obvious to even bother going into. But whereas broad trends were always going to have to a knock-on effect on the city, it’s the knotty state of affairs at micro level that are at risk of tripping it up.

As you can probably already tell, Chicago isn’t the easiest place to catch an easy break. Marea Stamper (The Black Madonna), Jason Garden (Olin), Gianpaolo Dieli (Savile) and Steve Mizek (just so) are four of Smart Bar’s current residents; all bear battle scars. Only Mizek, the brains behind Argot and the ever-excellent Little White Earbuds, is a native Chicagoan, but the “struggle to get any effort realised” for both label and website mirrors his compadres’ various stories of rocky beginnings in town. “There’s always been a lot of innate competition inside of Chicago,” Mizek sighs. “A lot of cut-throatness, and not necessarily a lot of community building. As a city we don’t really support each other, let alone the next wave.”

Set against somewhere like Pittsburgh, states Mizek, where a centralised district houses a tight-knit electronic music clique, Chicago suffers for its size. Stamper agrees, suggesting it entrenches a natural inclination to lean on preferences. Dieli underscores the point: “It’s hard to patronise different circles, even if you would like to. It’s just not cost effective to traverse the city to visit different parties that exist in different scenes.” Given the relative cultural remoteness of Smart Bar in uptown Wrigleyville, the venue’s endurance is all the more impressive.

But a disparate layout is not even the half the story – the greater metropolitan areas of London, NYC and Tokyo are all stitched together from much larger boroughs, and none fall prey to self-destructive tendencies in quite the same way. Instead, what could just be a minor pain runs out a major problem: longstanding socioeconomic and racial divides cast North Side and South Side as separate entities; geographical borders become artificial barriers.

A City of Two Tales, if you will.

“They trip on every aspect of house!”

When it comes to house, the opposing perceptions are that the predominantly older, black, working-class South Siders are unadventurous and stuck in their ways, whereas the younger, mixed, well-to-do North Siders are unappreciative and stuck up. Both camps have valid grievances – I mean, can you really blame someone in their 50s for seeking out a welcoming spot to hear their ‘oh, that’s my shit!’ jam? – but given the lineage of such radical and progressive music began downtown, and given the early adopters still loom large, the perceived intransigence of the South Side set is cast in a harsher light. Discussing the matter with the the affable and hyperactive Czarina Mirani, editor of dedicated house monthly 5 Magazine and an aficionado of the soulful sound, it’s immediately clear she seeks to redress the balance, giving both sides their fair dues. That approach doesn’t last long.

“It’s not animosity as such,” she starts, before ceding that South Side audiences’ innate scepticism and rejection of anything but the classics is paralysing. “You’ll clear the floor if you try something new, but try the most tired song and you’ll pack it. They’re so lost in their own world it’s incredible.” Out of dozens I speak to, Johnson [hard at work below] is the only artist confident enough in his ability to entertain a South Side spot without needing to make concessions to the dance. Part of that is the lingering braggadocio of a hustler-auteur, but he’s not wrong. “There’s literally thousands of us DJs here; there’s a good hundred of us who are famous; then there’s a handful of us that are super famous worldwide;” but when it comes to straddling the divide, “there’s only two or three different people” able to get away with it.

There have been times when matters of taste have resulted in outright tastelessness. Mirani exasperatedly recalls watching a reunited Ten City get booed – hardly a challenging proposition, and not exactly a one-off either, as anyone who tuned into last year’s Boiler Room Chicago broadcasts might remember. There was a wince-worthy moment during Phuture’s otherwise-incendiary reunion performance where “Fantasy Girl” got fumbled. Johnson, also on the bill that night, laughs at the memory. “People were hollering at them, like, ‘how the fuck you forgetting the words!’” Given a 24-year hiatus, you might expect some leeway. Nope. “It’s a tough room, man.”

None of the above will come as news to anyone in the city. The schism has been a prevailing narrative for as long as house has. A handful of seminal 12”s even tip the hat to the underpinnings of segregation with ’North Side’ / ‘South Side’ embossed on the runout – and given the early 90s boom, they had the liberty of being cheeky with it back then. Skip forward to 2015, and as flesh blood has all but dried up, it’s becoming a pronounced issue.

Russell Pike, operating under nom de plume Russoul, is one telling example of how scene politics manifest in reality. An r’n’b singer by trade who toured with local dons like Common and a pre-blind-seething-rage Kanye, his rejection of the machoism and corny casanova lifestyle at the bottom of the heap drew him to house, where he was taken under Cajmere’s wing, lending a voice to a number of his recent standouts. “There was no acting or facades necessary; it was much more warm than any other industry I’ve been in.” Sadly, it didn’t last. Jealous factions outside the Cajual fold felt “like I wasn’t a purist, like I was unofficial and contrived,” and constantly sought to undermine him at every turn, forcing his hand to retreat from the stable. “Instead of saying, ‘let’s invest in the schools and bring up the new guys’, they bully the upcoming acts. The legendary cats won’t let go of yesterday…it’s like they’re war veterans!”

Generally speaking, Pike’s mindset marks him as an outlier. He’s openly honest about courting endorsements and gripping new technologies, suggesting that while “old Jupiters and old Voyagers might have great sound, so too does the new software” that some seasoned producers steadfastly reject. Normally laid-back and cheery, when on topic his intonation rises sharply. “The whole movement came from young people – not old, bitter, angry people that are mad they’re not getting a piece of the pie no more. The shit they were loved for was the cheap Casio keyboard sound they bought at the drug store for $15 that could compete with a studio that was a million dollars. That’s what made Chicago so hot.” He slumps back. “They trip on every aspect of house!”

“There are people who are famous around the world but couldn’t fill a closet full of people here – that’s super fucked up.”

Pike’s fairly rough treatment might be a special case, but he’s by no means the only one pointing out the deep resentment of a whole subset who feel they have been left behind in some capacity. With semi-legendary DJs sleepwalking into irrelevance, seemingly unable to arrest their decline, this bears out in cloistered protectionism over what they feel it all should look like. It’s playground stuff, really: taking your ball and fucking off home.

Stamper pours scorn on those acting as if there’s no solution. “To say that there’s going to be this young generation that’s completely insulated from the rest of the city, and that we’re never going to reach out – well, that’s a really good way to starve yourself of ideas.” There’s a dual irony at play here: firstly, in ring-fencing ‘house’ in this manner, they are alienating an already disillusioned, threadbare bracket; the second is that the ingrained attitude of the genre’s self-appointed guardians runs directly counter to the inclusive spirit it once stood for. The background commotion is becoming overpowering.

The counter-argument goes that digging your heels in does not amount to an act of aggression. This isn’t entirely without merit. Given those directly under threat of being cast adrift are of a certain age and disposition when real life concerns takes precedence, when faced with a stick or twist decision, most invariably chose to cling onto what they have. “They don’t have the force or the ability” to do much else, reasons Johnson ; “they have kids to feed and bills to pay”. This is true, but there’s a distinction to make between watching your turf and blocking the path.

There is yet another wrinkle in all this. Many upper-tier acts are mainstays abroad, but practically ghosts at home, cropping up on bills only a handful of times a year; others saturate the local circuit, but struggle to make a dent internationally; a significantly larger proportion still can’t get a foothold in either camp. It’s not just affecting homegrown talent, either. As talent buyer for Smart Bar, it’s a problem Stamper frets deeply about. “There are people who are famous around the world but couldn’t fill a closet full of people here – that’s super fucked up.” Mizek chimes in wearily, saying that while he can throw quarterly Argot showcases in New York, the lack of sustained growth at home makes him feel insecure it would come off. “One of Chicago’s biggest weaknesses is that it doesn’t pay attention. It’s something that’s been part of the narrative for a really long time.”

While the state of play is fractious, the house community isn’t crumbling inwards. “It’s not necessarily like everything’s dysfunctional and nothing’s working,” says Emil. “It’s just a matter of this being the status quo.” Yet this very status quo – a mesh of in-fighting, myopia and bottleneck – is badly damaging the city’s prospects. Chicago has the talent, but not necessarily the means to properly support it. It’s the kind of impasse that requires a sharp wake-up call to shock people into reality.

On March 31st 2014, the city got just such a call.

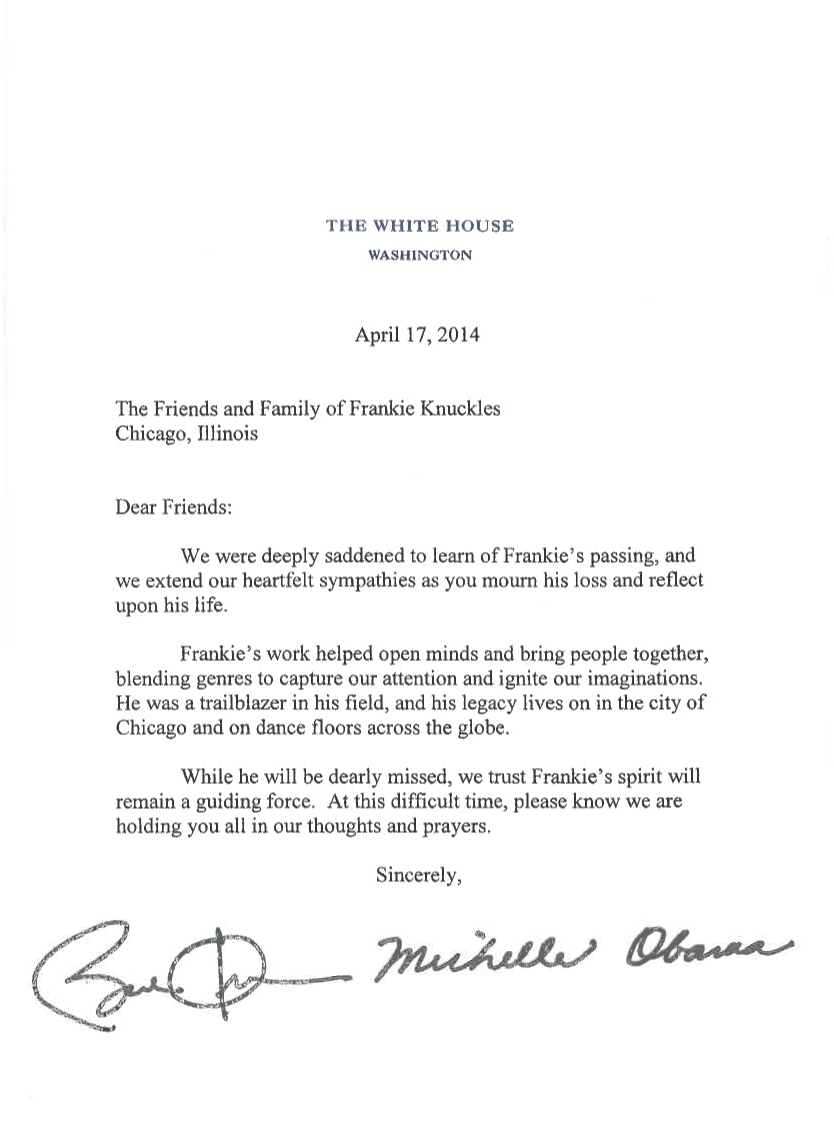

It might seem a little strange to get this far having not yet mentioned Frankie Knuckles. That’s purposeful: you need the negative for context and balance. Frankie Knuckles represented the positive; he still does. It’s open to debate whether he was the all-time greatest DJ, or had the strongest body of work to his name, but what’s irrefutable is his place as house music’s leading light. It rings especially true in Chicago, where he remains a talismanic figure. They don’t call him the Godfather for nothing.

Everyone has their own cherished memory: Emil being transfixed at the House of Blues’ Thanksgiving extravaganzas Frankie hosted; Mirani revelling in his quiet dignity post-amputation, having his ear talked off in the booth by an excitable fan, yet gracefully offering her advice until he literally had to be tugged away; Loftis spinning a great yarn about Frankie failing to secure a loan for the liquor-free Power Plant from a gaggle of incredulous suits at the Small Business Authority (“they thought our books were forged!”), but nonetheless convincing a junior female staffer to come down to the venue on a Friday night before converting her to the faithful.

As well leaving thousands of individual imprints, it goes without saying his wider impact on popular music, let alone Chicago house, is unquantifiable. There are books and films dedicated to his story, tracing a path from The Warehouse’s opening night to “The Whistle Song” topping the US Dance chart in the year I was born (!!) – I can’t get close to matching any of that for detail. But spending only a few days on the ground opens you up to just how integral he was. The trickledown of his pioneering success permeates everywhere.

“Frankie was a top man for noble shit.”

His role in the rise of Smart Bar provides one such historical flashpoint. Frankie was the first guest to play the club way back in 1982, needing a fair amount of coercion by owner, and later dear friend, Joe Shanahan at a time when racial tensions were still rife. For context, Shanahan himself had been hauled off the decks by an incensed owner of another joint a few months prior. His crime? Playing a funk record – for fear it would warm the all-white crowd toward blacks. (Alien as it may seem, this was by no means uncommon. Implicit colour barriers were still enforced nationally in the arts and media it wasn’t even until the following year that David Bowie went public, grilling MTV for their “lack of Negro artists.”)

Frankie agreed to the gig in the end, crossing the divide in what was quite a big deal at the time; he retained resident status for thirty-two years thereafter. Unwittingly, moments like that subtly but powerfully helped dismantle existing perceptions of culture, race and sexuality in Chicago, affording freedom for those that came next to stretch their legs and experiment without fear of pigeonholing or censure. These personable little gestures play a big part in why he’s so revered, helping ground the myth in reality. “If you got in a fight with someone and Frankie stepped in, both of y’all were going over to his house for dinner,” Johnson smiles. “Frankie was a top man for noble shit.” Given what the first wave found themselves up against from the outset, it places things in perspective. The ongoing quibbles look very petty indeed.

With a year’s distance since Frankie Knuckles passed, thoughts have gradually turned who’s next in line as the city’s ambassador. Everyone I speak to is at pains to avoid 1:1 comparisons, but most everybody agrees that Derrick Carter naturally fits the mould. It’s not as if you can draw a straight line between them, explains Emil, “but if there’s someone who is going to stand tall and be the representative moving forward, it’s certainly going to be him.” Where Frankie was a gentle soul, Derrick is bold and aloof, but unshakeably loyal to his city, and carries its hopes adroitly. Think Jeff Mills in relation to the Belleville Three and you’re not far off. “They were both stewards of the party,” Dieli posits, “but Derrick is special, and wholly unto himself. He carries that torch in a unique way.” Stamper nods in agreement. “He’s the undisputed heavyweight champ. He’s the man!” Yet heavyweight champ or not, he still has some way to go.

The Chosen Few Picnic is an important ritual for the Chicago house community. We’re talking 40,000 people coming out to eat and drink and revel and jack, dispensing any notions of a stale scene. Celebrating the 25th anniversary this year of what was literally a few dozen old friends catching up, it’s the kind of jumbo-sized, ecclesiastical gathering you’d expect from the first city of house; a proper Midwestern barn-burner. Yet, while it positions itself as the centrepiece in the calendar, this is the first year Derrick Carter has been invited to play. Consider how palpably strange that is: a man held aloft globally as an icon, only officially recognised by some in his own backyard in 2015. It’s the right kind of gesture, but one they don’t make often enough.

Out for dinner with Smooth and Loftis, I press them on the matter. They reach for Mike Dunn, who a few years back was welcomed into the Chosen Few’s inner circle, as the baby of the group. Mike Dunn produced his first record in 1987. Asking direct who the youngest person to have played at the Picnic in recent years draws pause. They turn to each other wearing bemused expressions, looking not unlike a pair of naughty schoolkids caught out. “We all have very youthful spirits,” begins Smooth, before tapering off with a wry smile; Loftis furrows his brows. “We’re just so involved with fuelling the fire, we haven’t given much thought about passing it on.”

This goes some way to explaining the cross-generational faults that, inadvertently or not, limit the city’s ability to move forward as one. These are not guys in any way bent on trampling others into the dirt, but just as Loftis blossomed under Frankie’s tutelage, that ethos needs revival.

“Chicago looks however we make it look”

There is a feeling that Chicago is slowly lumbering out of a transitional phase. That people are acknowledging the loose outline of an elephant in the room can only be a good thing. Johnson received a spike in international bookings following his Boiler Room appearance last February, but it was only a few months later, after the news about Frankie had sunk in, that anything triggered locally. “Suddenly my phone started blowing up! Promoters on the South Side are calling for the first time in years,” showing contrition and a hitherto-unseen willingness to buff up on what they’d been missing. “Trust me, it’s coming together. Even a year from now we’ll be having a different conversation.”

A resurged taste for residencies on the circuit is helping enable this. For his part, Johnson finally took up a regular Wednesday stint just a few weeks back, having demurred for years. Mirani, who extols base-level “trust in the party” as the single most valuable factor in the upkeep of a healthy club culture, spotlights Queen! at Smart Bar as somewhere doing it right on a regular basis. Queen! includes Gramaphone chieftain Michael Serafini and Carter amongst their ranks; Carter, predictably, is adept at juggling international festival slots and Sunday slow-burners with consummate ease.

Expecting success clean off the bat is naïve, reckons Dieli, but emergent green shoots are a hopeful sign. He points to Jeff Derringer’s Oktave series, arguably the city’s highest quality techno night, as an example of how to forge consistency without much compromise, “earning the trust of his local audience over a long time”, before embarking upon more challenging line-ups. Then again, says Stamper, one event recently “ate shit” on the door – even that ‘closet’ was only half-full.

In stark contrast to the underhand promoter politics witnessed in lot of other cities, those making it happen behind the scenes seem to be the most cognisant and proactive faction operating within Chicago house right now. Their vision, after all, is a driving factor behind packing out dancefloors; it’s on them to present the same cluster of artists in a refreshed light, creating a conducive cushion for their music to sit. If the infrastructure weakens, the scene wobbles – and if that strikes you as a little unfair, well, it is. But given the parlous state of play, someone has to take a firm lead on the issue. Even if it means spoon, or even force, feeding from time to time.

Speaking to the little coterie of Smart Bar residents, and it’s abundantly clear they get it. “A few of us sat down and decided to try and get into these scenes we’re less familiar with, and get to know people; for it to be a little more of a give and take.” Garden isn’t hedging any bets about whether it will prove a successful move, but seizing the initiative has “brought people to our parties – without us badgering them.”

Garden’s wittily-titled Deep Turnt night, co-run with Studio Casual, who comprise 2/3rds of Stripped & Chewed (the label-cum-promoter trio that saw out Stamper’s Gerd Janson-approved stunner “Exodus”), is indicative of a new kind of event bubbling up in the city. Recent headliner Gunnar Haslam may be an Argot affiliate, but booking him represents an outstretched hand. His sound makes for a neat bridge between house’s empathetical warmth and the kind of grit finding favour in the $5 basement raves thrown by Pilsen’s art community. “We can do all the outreach we want,” Mizek says, echoing Garden’s caution, “but it doesn’t necessarily mean the kids in Pilsen are going to migrate to Smart Bar for something they don’t care or already know about.” Granted, but right now any step outside a comfort zone is a step in the right direction.

Parsing how the changing face of festival culture has gradually inured hacky-sacking collegiates and creatine-addled bros alike to big room tech is a whole other fucking article in itself – but the sound’s increasing visibility plays a role in undermining unity. Age-old ‘mainstream’ v ‘underground’ debates are guaranteed to colour people’s opinions of venues like Spybar, placed at the lip of the city’s central Loop. It’s a precarious tightrope to walk: snobbery over yer Guy Gerbers and Marco Carolas persists, with an affiliated (and oft completely baseless) concern about gauche bottle service crowds occasionally drawn by marquee names. The diligent, dedicated work ploughed into festivals, loft jams and keeping weekday events steady gets chucked out the window as soon as the deep-v and tank-top squadron roll through.

Stamper is having none of it. “We need to be inclusive, and lead with solutions. As far as these two venues go, we’re committed to bridging that gap, and trying to remove a little bit of the tribalism.” Words like ‘colleagues’, ‘partners’, ‘friends’ crop up a lot as she details at length the strive to move “away from compartmentalisation” and toward “thinking more civically. Chicago looks however we make it look.” Cynicism will always abound, but working with the major league while keeping one eye fixed firmly on the niche is a canny way to go about it. The city may want for a core ‘temple’, but by reaching both ways across the aisle, promoters are helping form a latticework stronger than individual parts.

But as admirable a job the men and women behind the scenes are doing, they can’t shoulder the burden alone forever.

“What can be done to pass on this legacy?”

I’ll reiterate what I said further (way further) up the page: I’m no spokesperson. Thankfully momentum is picking up organically, and there’s a sanguine feel about the future, but it needs a measured approach lest it splutter. So while I lack authority, here’s what I believe everyone can do.

Cross-party dialogue is already up and rolling; this needs to go further. A lot of the problems outlined aren’t even problems per se, they’re merely the way different actors within the community interact. Or so often, don’t. Emil sees the spread of Jamie 3:26, DJ Hyperactive and Gene Farris at our Gramaphone broadcast as emblematic. “Jamie and Gene probably don’t hang out too much together; Jamie and Hyp probably don’t hang out too much together; Gene and Hyp probably haven’t seen each other in a fair few years! They just have their sound and their groups of people.”

While it’s a great thing to have such a vibrant scene that individual pockets exist, isolation engenders stagnation. Moreover, if this is discernible on just a single bill of second-wavers, think about how that bears out given the multiple problems that plague Chicago as a whole. It doesn’t need to be cathartic, and it doesn’t need to procure immediate results. But no-one stands to lose anything by at least coming to the table.

From there, discussion would hopefully lead to action. Older house heads need to lower the drawbridge. All it might take is a minor shift in mindset: for what I heard about purposeful bitterness, my experiences fell closer to seemingly-innocuous ignorance. That needs to change. It’s unrealistic to expect those who make a living out of music (which is in of itself an increasingly tricky thing) to actively pour resources into siring apprentices at the expense of their own security. But dissemination of information is a healthy first step.

Outreach can be a two-way street. As Mirani notes, South Siders broadly “have no idea how to use current technology to market themselves.” Assisting the progenitors in properly reaching their audience will drive commerce, given that they’re the ones accustomed to actually buying physical. Right now, I’m staring at a brand new Joe Smooth record, featuring none other than George Clinton; yet I can’t find a single thing about it online. This is a tad disconcerting. Technology and trends move at lightning pace, and it’s understandable how this necessitates a reluctance to engage for those who haven’t grown up in tandem with the internet. Collaboration, mentoring and fostering relationships will prove mutually beneficial.

Pike, having had his fingers burnt, is understandably passionate here. “A lot of the older legends could be going to the grammar schools, dedicating time to teaching and training.” Even a simple gesture like giving “young children an opportunity to experience their stories,” is a forward-facing investment in the artform. Contrast with Detroit is telling. The city’s techno community might have a crotchety reputation, but scratch below the surface and you’ll see Derrick May-led fundraisers, ‘Mad’ Mike Banks coaching baseball and all manner of educational programmes; plus, Kyle Hall and Jay Daniel playing peak sets at Movement years before they were legally allowed on the premises. The denizens of the D might be outwardly spiky, but they don’t half look after their own. Chicago could learn from this.

In all honestly, there is a lost generation. Very few people my age are breaking through, or even bothering to. Set against footwork’s foothold on the South Side, where 24-year-old DJ Earl is at the vanguard of Teklife, and it looks bad. It’s going to be harder now that Chicago house music has less of a immediate presence at street-level – anyone in vague proximity to a radio or any moving vehicle in the summer of ’99 can probably still ‘woo!’ on cue to “Get Get Down” – but making sure the same problems aren’t repeated is the challenge to be met.

Because here’s the rub: thriving heritage events look a little shortsighted when there’s a depleted pool to carry it on. Without concerted effort, you risk Chicago going the same way as Memphis – turning into a place of museums.

These are ambitions for the longterm that can be enabled by movements in the medium. The most pressing, but also most precarious, pillar of this tripartite plan to put the jumper cables to house involves the Godfather. The immediate wake of his passing saw a raft of unauthorised and downright spurious benefit events set up, while some grief-stricken members of the community felt compelled to do similar, coming from a well-meaning place but with the execution all off. It was, I’m told, a shitshow. The Frankie Knuckles Foundation was duly established, in part to afford greater protection of his name and likeness. I can attest to this: Boiler Room only got the official greenlight for our commemorative event, featuring four key members of the Foundation – Frankie’s hand-picked warmup Elbert Phillips and the Chosen Few’s Alan King, as well as Serafini and Carter – after months of meetings and many layers of (justifiable) scrutiny.

A memorial in Millenium Park last June 3rd drew the kind of numbers only the Chosen Few Picnic can touch: tens of thousands getting loose in reverence of their collective hero. It unified the city. “He was one of those dudes who threw his magic dust in, and this cool thing happened that never could unless he was involved with it. Boiler Room,” Emil kindly mentions, “was a very similar situation to Millennium Park.” It was far too raw then to start putting heads together and using it as a jump-off – loss is complex enough to process on a personal level, let alone when it concerns a figurehead – but though the city still smarts today, the dust has now cleared, and it’s high time to kick on.

Communal celebrations are one thing, but they really only act as a sticking plaster. Exercising due caution over misappropriation and opportunism is only right and natural, but those closest to Frankie’s estate need to open up a little, and be more proactive in enacting change. Concentrating on handing the torch over, not just keeping the flame burning for those for whom he is already dear, needs to be the focus.

Mirani says she has lost sleep mulling it over. “I’ve asked myself a million times: ‘What would Frankie want? What can be done to pass on this legacy?” Aside from just preserving his memory, I wish for the Foundation to do stuff with younger kids. I know he would love to champion the new, and to do something with the city. It’s so needed.” Off record, a member of the board for the Foundation alluded to something major to be unveiled in the coming months, so it’s all absolutely on the cards, and the Foundation is evidently in more than capable hands.

But callous as it may seem, as long as this ethereal quality hangs in the air, it has to be capitalised on for the greater good. Hopefully it won’t be too long before the training wheels can come off.

In the 18-odd months of involvement with Boiler Room, I’ve been fortunate enough to experience a lot of unforgettable events, but the two in Chicago were truly something else. We linked with people who drove hundreds of miles to be part of it, and the rundown of Chi cognoscenti who turned out remains head-spinning: DJ Heather and Gant-Man; The Warehouse founder Robert Williams and D.J. International’s Rocky Jones, who had to be carried down the Smart Bar stairwell; members of Frankie’s estate and Ron Hardy’s family. Everyone was warm in spirit and effuse in thanks. But it only threw further weight behind the question nagging away in the back of my mind: why did it take a couple of New Yorkers and a Londoner flying into town with some cameras to get wheels in motion again?

In the 90s, the genre faced down strong headwinds from hip-hop, techno and rave, yet adapted and came through shining. Its relative simplicity lends it a malleable quality that few can match; as a building block, it sidles up nicely against pretty much anything. Producers would do well to take stock of the others in the city outpacing them: take heart from footwork’s ability to dice speed and serenity, or lend an ear to the Pilsen kids fumbling their way through curdled, mutant sounds; or even look a little closer to home, where Russoul is laying his dulcet tones over the kind of deep tech hybrids that have flooded dancefloors as of late.

The most effective way to fill a void, or to combat something that irks you, is by making a statement of artistic intent. The strike rate isn’t always 100%, but it doesn’t have to be. The weight of expectation has become suffocating, and that’s crippling development. After all, haphazardly layering rudimentary drum patterns over spliced reel-to-reel disco edits was how it all began (or thereabouts). Wringing hands over this sacred notion of ‘house’ going awry isn’t helping. Right now, it’s stuck in a locked groove.

But most importantly, it’s time to cut the shit. It’s hard to emphasise how strong the house community is without being cornball. Yet in recent years, it’s paradoxically been those without born connections straining their necks furthest in trying to help un-gum the system. It’s going to require arms laid down, gestures from all sides, and hands placed in the middle. After all, this is city that created an entire global culture out of nothing. C’mon.

Put simply, music this positive shouldn’t be weighed down by such negativity. It’s woefully petty, entirely avoidable and, crucially, out of step with its founding father. To Stamper, recapturing and banking on his enduring spirit is vital.

“When you see the way his memory brings us together – a city rallying around what one person meant to them – it’s not only because of him as a human being. To Chicago, Frankie Knuckles was not only a real person, but an idea and a set of values.”

“Those things don’t go away, ever. They’re here to stay.”

– – –

– Thanks to Tony Martin, Cratebug & Elbert Phillips for the photos; ‘Davey Dave’ Mason for his tireless work; and to all those who contributed to the shows & this piece –

– Boiler Room had the pleasure of returning to Chicago (and Detroit) six months after this piece. That trip saw performances from legends like DJ Heather, Farley Jackmaster Funk and Virgo Four, as well as the aforementioned Joe Smooth, Steve Mizek & Savile and Olin. For all those and more, HEAD HERE. –