Hard Times

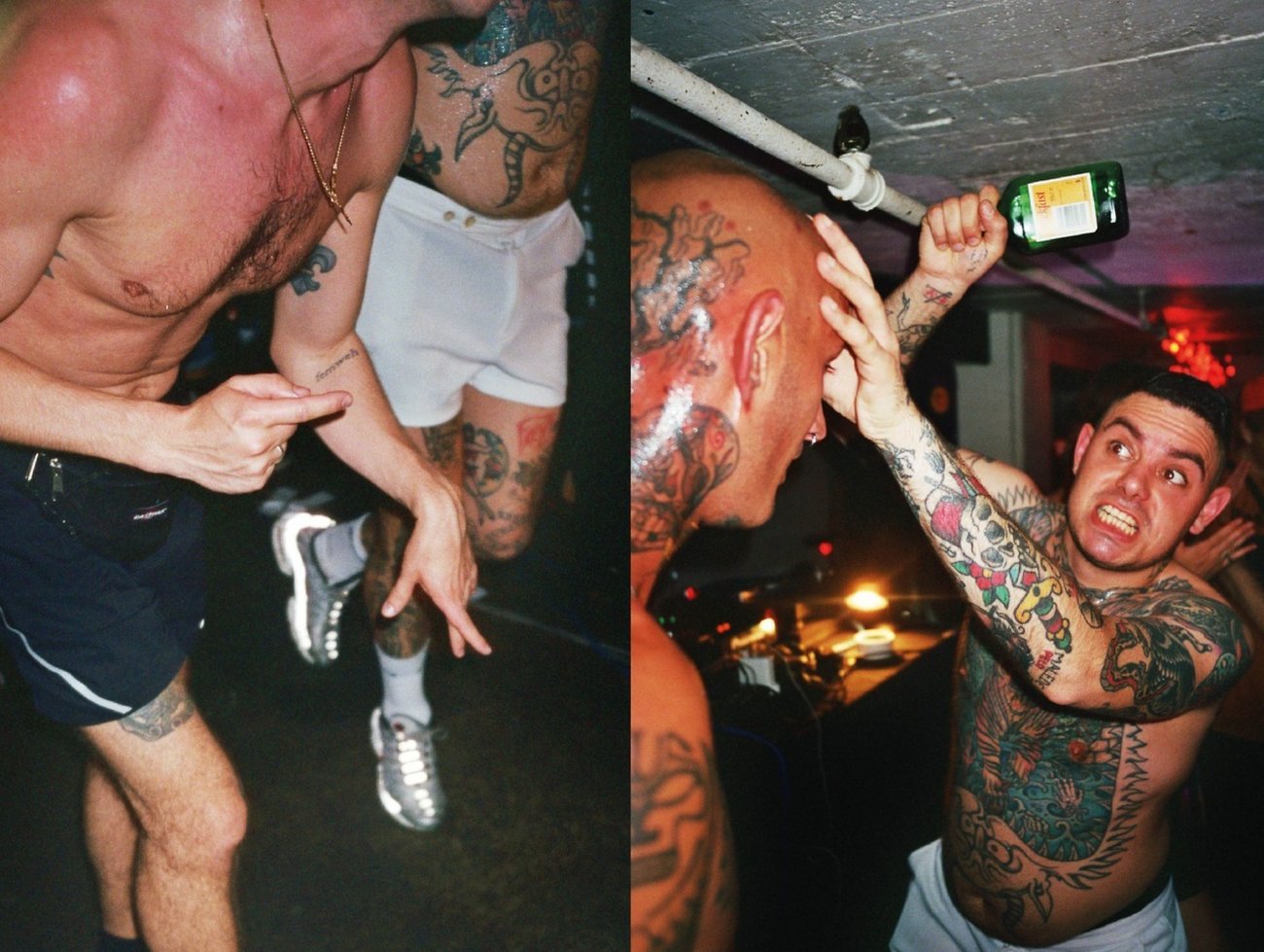

Profiling the extreme scenes soundtracking a fractured world.

As long as there’s been dance music, there’s been hard dance music. Beginning with the astringent acid house sounds of Phuture and the militia-techno of Underground Resistance—and continuing with the rave and techno revolutions Chicago and Detroit have spawned since—club culture has always had a dark side.

Today hard dance resembles a knotty matrix of sub-genres covering a broad tempo range, from the 1000+ BPMs of extratone to the more moderate 60-140BPM spectrum of doomcore. It’s comprised of small regional scenes, like donk, bounce and bassline in the North of England, alongside the huge Dutch hardcore and German trance industries that have gone on to conquer the world. (Hardcore and trance have their underground scenes too of course, popping up in places as far flung as Copenhagen and Shanghai.) It’s multitudinous, ambiguous and deeply subjective: hard dance is what you make it.

There’s been something else driving hard dance’s re-emergence in recent years: the social political climate. It can safely be said these darker sounds reflect the world around us. The eerily prescient apocalyptic techno of Marc Acardipane, which first surfaced in 1989 via Frankfurt label Planet Core Productions (PCP), has never felt more like mood music. Yet as Acardipane himself believes, where there is darkness there is hope. Hard dance has a long history of community and unity, from the original meaning of “gabber” (a Yiddish word for mate), to the Hardcore United anti-racism movement of the millennium, all the way through to the ground swell of inclusivity that’s defining clubbing today.

The commercial peak for hard dance came in the ‘90s, the moment when underground music crossed over into popular culture before dipping back below again. In the UK, The Prodigy, SL2, 2 Bad Mice and Baby D led the charge, pioneering a breakbeat techno sound that would mutate into darkcore and jungle around ’93, and later drum & bass. In Belgium, the hoover and R&S Records were defining rave, while in neighbouring Holland, distorted kick drums and distinctive dance moves were sweeping the nation. Hard house emerged with Tony De Vit as its ringleader, and hard techno began to calcify around the Berlin club and label Tresor, which served as a convergence point for respective scenes in Birmingham, London, Edinburg and Detroit. And then there was trance.

Hard dance was understandably big business during this time, especially in Europe. ID&T in Holland set the bar for mega raves high with their first Thunderdome event in 1992, drawing over 30,000 people to an ice skating arena in Friesland. From then on they just kept getting bigger. The international success of Thunderdome, and the national gabber craze it amplified, made ID&T one of the most significant dance music enterprises in the world. After the scene collapsed towards the end of the ‘90s, ID&T moved into trance with events like Trance Energy and Sensation, pushing production standards to new heights and turning DJs into superstars. Hard dance is still massive in Holland. In 2017, 40,000 ravers turned up for Thunderdome’s 25 year anniversary rave – the largest indoor hardcore meet in history. Whilst Q-Dance, the company that cashed in on hardstyle (a descendent of trance and hardcore with a major following worldwide), continues to host some of the biggest harder styles events and festivals in the country.

The Netherlands will probably always be thought of as the home of hardcore, yet all over Europe micro-scenes are now cropping up all over Europe, driven by a new generation of artists and promoters expressing their love of hardcore with a newfound openness.

Whether it’s the humorous irreverence of Polish crew WIXAPOL S.A., the dutiful homage of Italy’s Gabber Eleganza, or the rowdy mashups of Casual Gabberz in France and Sweden’s female-run collective Drömfakulteten, the malleability of hardcore is being tested and redefined. And it’s not exclusively confined to Europe. Take Shanghai crews Genome 6.66 Mbp and SVBKVLT, global collective NON Worldwide, who explore racial and sonic diaspora with beats as hardline as their politics, or the 300BPM Singeli music from Dar es Salaam, Tanzania’s own answer to gabber. The world is waking up to hard dance. But why now?

Much of this is timing. Just like every other scene, hard dance has evolved over the last 30 years, experiencing cycles of growth, decline and renewal, triggered by new technologies, infrastructures and ideas. Right now hard dance is in a period of rejuvenation that’s as much about looking back as it is forward. Historic institutions like Thunderdome are returning to the fray. Documentarians like UKGabbers and Gabber Eleganza’s Alberto Guerrini, and visual artists like Boris Postma and Henrike Naumann, are archiving hard dance’s past through exhibitions and performances that dissolve the boundaries between art and clubbing. It’s part of a ongoing process of cultural re-appropriation and re-evaluation that’s seen hard dance subcultures inspire high end fashion lines and streetwear brands, from D’ior to Nike .

All of this has been helped along by backing of high profile tastemakers in clubland. Nina Kraviz, who not only raises BPMs with her DJ sets but has recently gotten more hardcore with the curation of her label трип (Trip), has helped widen the remit of hard dance, opening it up to fans from outside the scene. Then there are innovators like Lorenzo Senni, who is using the prodigiousness of Warp Records to change the way we think about trance. It’s all contributed to the de-stigmatisation—or rather legitimisation—of hard dance sounds, a shift reflected in enthusiastic media coverage. And about time.

For Christoph Fringeli, labelhead at the experimental label Praxis, hard dance music has always had a socio-political conscious. His Dead by Dawn squat parties in Brixton in the mid-‘90s were a crucible for speedcore and social activism. He still runs squat parties from his current base in Berlin, whilst his magazine Datacide and label testify to a scene that was critically informed, reflective and socially engaged. It still is, if you know where to look. Queer and collectively-run parties like mina in Lisbon and Herrensauna in Berlin, for example, provide safe, inclusive spaces for artists and fans to share in holy hard dance communion. There has never been more cause to put aside differences and band together in the dance than there are now. These are hard times.

Written by Holly Dicker

A part of Hard Dance, a Boiler Room series exploring the hard and fast fringes of club culture.