Boiler Room & Ballantine’s Scotch Whisky kick off 2016 with the ninth instalment of our collaborative Stay True Journeys project. We are heading to Latin America once again, this time to Brazil. The lineup features both homegrown talents and overseas ambassadors of Brazilian music, including: Todd Terry, Gilles Peterson, DJ Nuts b2b J Rocc, DJ Tahira and DJ 440. In the lead-up to this very special event, we reflect on just how much of a global impact Brazil’s popular music has made over the last hundred years – from samba and bossa nova to tropicália, funk carioca and beyond.

At the heart of Brazilian music beats a samba drum

In the early 1920s, a group of talented Brazilian musicians called Oito Batutas (pictured above) set foot in Paris for the first time. The were led by flautist Pixinguinha, a samba musician who was a star in his native Rio de Janeiro, well loved in seedy cabarets and high society ballrooms alike, thanks to tunes such as “Carinhoso“. The group also included Donga, the composer behind the first ever samba pressed on record, “Pelo Telefone”; and João Pernambuco, a guitar player from the northeast of Brazil.

Parisian audiences liked what they saw and the group ended up extending their stay for six months in the French capital. While there, Pixinguinha fell in love with the saxophone. He brought one back to Brazil and incorporated it into his samba music, displeasing many a patriotic purist. The trip had attracted criticism before it even started. The press carried articles lamenting that the group were promoting a “black, inferior and backwater” image of Brazil. This was not strange for the time, as the country had abolished slavery only thirty years earlier, and samba was yet to achieve its status as the nation’s premium genre.

The Oito Batutas tour is the first example of a longstanding relation between Brazilian music and the rest of the world. Although Brazil may trail countries like Jamaica or the U.S. in global musical influence, its sounds and rhythms and artists have conquered party audiences and music collectors worldwide. Possibly the most prolific example of Brazilian music being strategically employed by a foreigner is Gilles Peterson. A figurehead that we look forward to welcoming at our Stay True Brazil event with Ballantine’s Scotch Whisky, Peterson been pushing the Latin American sounds to London-based crowds and beyond since the 1980s.

Contemporary DJs Tahira and Nuts, who also join us in Brazil next month, know this trend all too well. Both based in São Paulo themselves, they have seen from first hand experience how well received Brazilian music is across the world, their own sounds having been lapped up by crowds from Tokyo to Stockholm alike. In countries such as Ireland, Austria and France, Tahira says people will stay on the floor regardless of whether they even know the tracks: “They ask about the music, about where to listen and find more of it.” According to DJ Nuts, no one shows as much love for música brasileira as the Japanese. “They study it intensely, to the point that they become more knowledgeable about it that us. I keep learning from them about our music.”

“The music that plays in Pará is not the same as in Bahia or Paraíba, but they all carry this groove that is very Brazilian.”

– Tahira

But, what is Brazilian music? The country is vast and the music diverse, but is there a common thread running through most Brazilian music? “Percussion,” offers Tahira. “It is diverse and unique at the same time. The music that plays in Pará is not the same as in Bahia or Paraíba, but they all carry this groove that is very Brazilian. Each region explores it differently. And then there is the strong connection to dancing. most of the times happy dancing, celebrating something.”

Samba, slaves and pre-history

Amongst all the rhythms, samba became the Brazilian music par excellence. The sound of urban Rio de Janeiro, then the nation’s capital, and its largest and most cosmopolitan city, with samba’s origin traced to its state of Bahia. There, black slaves’ dancing events had been called ‘sambas’ for centuries. The term is of obvious African origin, a corruption of the word “semba”, whose origin historians trace back to Angola or Congo, key exporters of slaves to Brazil. ‘Samba’ caught on as a term for a party in many Brazilian areas, with the music not necessarily related to what later became known as samba. In late-19th century Rio, samba parties – which doubled as community gatherings for the nascent favelas, attended by families and people of all ages – were considered dangerous and criminal by the white population, and suffered from constant police surveillance. The end of slavery helped make samba more acceptable. Its infectious polyrhythms, carefree spirit and upbeat vibe gradually proved to be increasingly irresistible to all walks of life in Brazil’s capital.

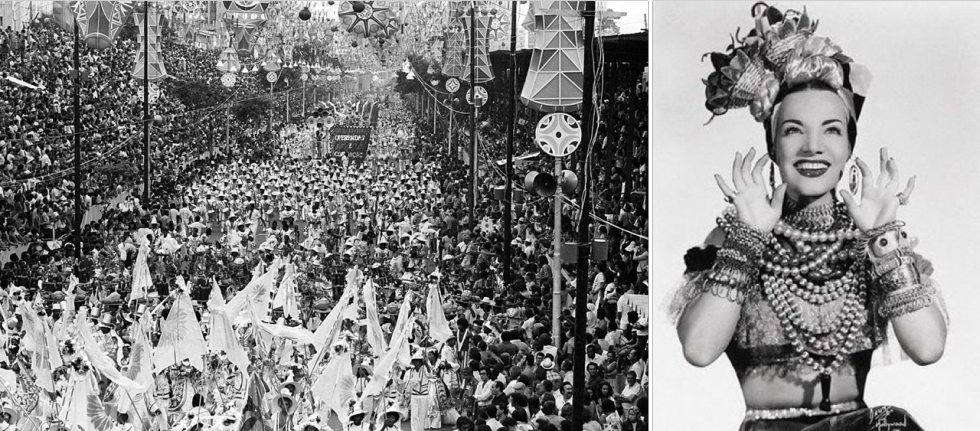

Left: Rio’s streets during Carnival in the 1930s Right: Carmen Miranda

Left: Rio’s streets during Carnival in the 1930s Right: Carmen Miranda

By the 1930s, samba had become the main style at Rio’s Carnaval, an established city event where people threw themselves into days of partying on the streets and in ballrooms. It was given a major national push with the launch of state-owned Rádio Nacional, which had among its goals the creation of a common Brazilian identity. Samba, still restricted to a certain parts of the Brazilian territory, was then promoted as the nation’s predominant musical style, and its artists featured heavily on the radio’s schedule.

From this period emerged Carmen Miranda, the iconic singer which, thanks to her Hollywood movies and fruit-bowl headpiece, came to represent many a gringo’s idea of Brazilian culture. Carmen’s roots ran deep in the Rio samba scene, and her career includes works with some of the genre’s best composers, including Ary Barroso and Dorival Caymmi. In America, she met with a different level of success and demand, starring in fourteen films between 1940 and 1953. In 1946, she was the best paid woman in the the States. Even so, tantamount appearances of Miranda dancing and smiling (but seldom speaking) seemed slightly more like a concession to America’s desires for the exotic.

Black, African-rooted and rhythmic; you can find the DNA of samba in most of the Brazilian music the world knows.

Black, African-rooted and rhythmic; you can find the DNA of samba in most of the Brazilian music the world knows. From “Mas Que Nada” to tropicália artists, and Marcos Valle to DJ Marky’s “Carolina Carol Bela”– a collaboration with XRS and Stamina MC that revisited the classic namesake tune by Jorge Ben and Toquinho. To this day, samba’s 2/4 syncopated beat, percussive undercarriage and hummable melodies continue to inform other genres of Brazilian music, still holding a place of importance and influence – even with the distinct strands of Brazilian pop music such as baile funk, axé and sertanejo. From the more popular “pagode” acts to alternative artists who reinterpret samba in innovative ways, there will always be a tip of the hat to samba.

Bossa Nova to the 1960s turn

Samba is at the root of Brazil’s most popular global genre: bossa nova. Created in the 1950s by Bahia native João Gilberto, bossa nova’s revolution in Brazilian music was similar to that of rock & roll in Anglo-American culture. But while Elvis Presley and Chuck Berry went loud, Gilberto and his cohorts sought to bring the volume way down. Gilberto stripped the samba drum ensemble down to a minimal rhythm, provided by no drums but his acoustic guitar, and sang in a soft, almost whispered voice. Thus, he emphasized the melancholic undercurrent hidden in much of samba music. “Sadness never ends / Happiness does” went the lyrics of “A Felicidade”, composed and performed by João Gilberto, Tom Jobim and Vinicius de Moraes – the holy trinity of bossa nova.

Jobim, of course, is the author of the most famous Brazilian song of all time, “Garota de Ipanema”. It was a worldwide hit between 1964-5, earning a Grammy Award for “Record of the Year”. The album on which it featured was Getz/Gilberto – a collaborative endeavour between João Gilberto and jazzist Stan Getz – which won another three other Grammys that same year. Bossa nova had become a successful Brazilian export. In 1962, New York’s prestigious Carnegie Hall maxed its full capacity by hosting a bossa nova revue to a 3,000-strong audience. American artists were soon on it, with the likes of Herbie Mann, Dave Brubeck and Quincy Jones releasing their takes on the sound – with Jones’ famous“Soul Bossa Nova” soundtracking Nike‘s Brazilian football advert. Even Elvis had a go, releasing his “Bossa Nova Baby” in 1963.

By the mid-1960s, the bossa nova craze had largely petered out in the America and Europe, its suave and lighthearted vibe relegated to hotel lounges and easy listening charts. Mendes thrived, however, following on his initial explosion with “Mas Que Nada”. He became a household name in America, and performed in the White House twice, to presidents Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard Nixon.

As the 1960s progressed, Brazil became increasingly subject to state violence and censorship. The optimism and confidence that inspired much of bossa nova had now given way to uncertainty and cynicism. At the same time, protest music and Anglo-American rock started to exert a stronger influence on a new generation. Jorge Ben, the original author of “Mas Que Nada”, released the song when he was only eighteen. His style was termed samba-rock, with a nod to the attitude and energy of rock & roll, but also a down-to-earth, working class outlook, shown through his lyrics about partying and romance. Ben went on to release a succession of important singles and albums that brought influences of black activism, psychedelia, soul and funk to this music.

Ben was a regular at the Beco das Garrafas, an alley in Copacabana crammed with live music bars which became a focal point for the bossa nova scene. There, a second wave of bossa nova musicians were earning their musical spurs. Many begun to play down the jazz influence and pursued a more ‘national’ sound which emphasized the samba roots of the music. The move was not only artistic but ideological, as leftist musicians expressed through music their rejection of American cultural imperialism – following on from the U.S.-supported military coup that had deposed left-wing president João Goulart in 1964.

Left: Jorge Ben Right: Marcos Valle

Left: Jorge Ben Right: Marcos Valle

Musicians forming this second wave included Edu Lobo, Carlos Lyra and Marcos Valle, who had an early hit with “Samba de Verão”. A restless innovator, Valle was soon attempting different genres and by the mid-1970s had tried his hand in soul, pop, funk, jazz, easy listening, as well as other Brazilian styles such as choro and frevo in Mustang Cor de Sangue, Garra and Vento Sul. “We always tried to stay away from the traditional”, he once explained. In tune with the times, Valle imbued his lyrics with protest and irony, such as in “Com Mais de 30” where he told the listener not to “trust anyone over thirty.”

The birth of tropicália

Going back and forth to the States to record and perform, Valle established a rich exchange with foreign audiences and artists, becoming greatly successful outside of Brazil throughout his career, certainly more than in his motherland where he is remembered by occasional hits (such as the 1980s funk hit “Estrelar”). DJ Tahira believes that Valle is “the most well known Brazilian musician outside of the country” alongside Azymuth.

Despite its sense of political defiance, the musical scene of the early-to-mid-1960s rapidly became a stylistic cul-de-sac, as purist as the original bossa nova wave. Artists was chastised for being adventurous, and using an electric guitar only equated to selling out to American musical values. Nowhere was this more evident than at the so-called live music contests broadcast on national TV, where musicians competed for the title of best song whilst faced with an extremely hostile audience, largely formed of university students. These events produced many historical moments in Brazilian music. One such moment had musician Sergio Ricardo wrecking his acoustic guitar on stage in protest, after being drowned by booing. Also among the heavily booed was Caetano Veloso, who delivered an enraged speech in response to the audience in 1968 (see audio footage in Portuguese below), critcizing their conservatism: “Is this the youth that wants to get into power?”

By the late 1960s, Veloso and Gilberto Gil, both from the predominantly Afro-Brazilian state of Bahia, were at the forefront of what became the next big thing in Brazilian music: the Tropicália movement. Tropicália was anything but purist, as it sought to revive the “anthropophagic” spirit of the 1920s Modernist movement, an enthusiastic embrace of highbrow and lowbrow cultures, popular and underground, native and foreign. As the song Veloso was trying to sing at the festival proclaimed, “É Proibido Proibir” (“It’s forbidden to forbid”).

Musically the Tropicalistas were shooting in all directions – drawing from fuzzy psychedelia, traditional samba chanting, orchestral pop, rock, Brazilian folk and funky rhythms, to name a few. Out of the movement came two acts known for their whimsical approach, as well as outstanding musical skill: São Paulo rock band Os Mutantes and Bahian singer Tom Zé. Revered for decades in their home country, both artists gained international recognition in the 1990s: Os Mutantes were named as a personal favorite by none other than Kurt Cobain, and Tom Zé was championed by ex-Talking Head David Byrne, who released Zé’s music on his Luaka Bop label.

Left: Os Mutantes Right: Tom Zé

Left: Os Mutantes Right: Tom Zé

The tropicalistas liberated Brazilian music to do whatever it wanted. As a result, the late 1960s to the mid-1970s witnessed an extraordinary amount of creativity and innovation. For many Brazilian music heads, this was a very special time. “Many albums and tracks that have influenced me are from the 1970s”, agrees Tahira. “It is a time of excellent musicians and fusions of sounds. A tremendously high quality of musical diversity”. Check the “Best Of” lists of specialists such as DJ Cliffy and the Mr. Bongo shop, and you are bound to stumble upon plenty of entries from this era. DJ Nuts explains more about this golden age: “The music industry was on fire in all styles, while political repression and certain trends helped to bring about a new youthful expression.”

It was a time where artists found a rare freedom from within record companies. At the same time, the vigilant eye of the government’s censors, and the very real threat of political repression, meant creators had to be especially inventive in their lyrics to circumvent accusations of subversion. Many of Brazilian music’s heavyweights produced their most daring works during this period: Expresso 2222 by Gilberto Gil, “Araçá Azul“ by Caetano Veloso, “Clube da Esquina” by Milton Nascimento and “Construção“ by Chico Buarque. It was around this time that the term MPB (Música Popular Brasileira) took hold, an umbrella term for a diverse range of post-bossa nova and post-Tropicalia musics.

From the northeast of Brazil came a succession of bands and artists with music that fused regional rhythms and perspectives with rock, samba, soul and jazz. Leading the charge were the Novos Baianos, from Bahia but Rio-based, with their electrified samba, carried by the virtuoso guitar of Pepeu Gomes and the sweet vocals of Baby Consuelo. Their energetic Acabou Chorare (1972) consistently upholds a high ranking in lists of Brazil’s best records of all time. Aside Novos Baianos, other northeastern artists that burst into the scene around this time included Zé Ramalho, Fagner, Belchior and Geraldo Azevedo.

The period also saw the emergence of a set of unclassifiable musicians, who offered unique Brazilian takes on jazz and jazz-funk. But to use these genre labels is to restrict the diversity and experimentation of works from artists like Hermeto Pascoal, Arthur Verocai, Airto Moreira and Azymuth. Pascoal put it better when he called it “free music” in his 1973 album (A Música Livre de Hermeto Pascoal). Born in 1936, this Alagoas musician became celebrated in the international jazz circuit, having collaborated with Miles Davis after only a few years of being active musically.

Azymuth, a trio formed in Rio de Janeiro, specialized in groovy Brazilian music. Their approach was more accessible, merging soul, funk and disco with Brazilian stylings, notably their generous use of the cuíca, a typical friction drum that is a classic samba sound. Although their biggest hit in Brazil is the vocal-based song “Linha do Horizonte”, Azymuth specialized in instrumentals, from the funky “Jazz Carnival” to the bright “Manhã”. Virtually forgotten in their homeland by the 1980s, Azymuth went on to achieve global recognition, playing extensively in Europe and Japan. “All collectors are into Azymuth,” says Nuts “Around the world, DJs started to get wise to our music because of them. People like Gilles Peterson.” Tahira agrees. “They mix American and Brazilian music in a unique and special way.”

Old school funk and the beginning of the DJ era

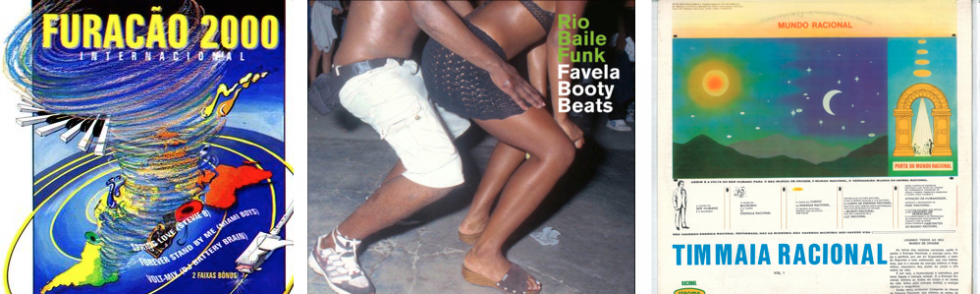

The soul and funk of James Brown and Stevie Wonder became so influential in Brazilian music that a strong “black music” scene developed in the 1970s. Its king was the larger-than-life Tim Maia, with others including Hyldon, Di Melo, Cassiano, Gerson King Combo and the mighty Banda Black Rio. Supporting them, a vast network of DJ-led parties flourished in the working class districts of northern Rio de Janeiro. Dancefloor dexterity, sharp dressing and black pride were big, and (somewhat predictably) viewed as potentially subversive by the military authorities. The scene was so big that soul and funk compilations were outselling Rolling Stones albums. Here was the ground for “baile funk” being laid – so, now you know where “funk” came from. The famous Furacão 2000 funk sound system descended from 1970s crews, Som 2000 and Guarani 2000.

In São Paulo’s poorer districts, farther from the city center, the same black music scene of sound systems and DJs was also thriving. Here though, apart from the sounds of Chaka Khan or Kool and the Gang, the sounds of samba-rock were also big on the dancefloor. This hybrid had come a long way since Jorge Ben in the early 1960s (he had long rejected the label) and indeed was applied to quite a diverse variety of sounds, from the swinging rhythms of Wilson Simonal to the Hammond grooves of Ed Lincoln. Its taste for older, lesser known records is reminiscent of the rare vinyl cult that took hold in the Northern Soul scene. Also, the samba-rock/soul-funk parties paved the way for São Paulo’s massive DJ culture. Its origins go back to the late 1950s, when a man called Osvaldo Pereira played records behind a closed curtain to a packed ballroom, calling himself the ‘Invisible Orchestra’. He was the city’s first known DJ.

The scene was so big that soul and funk compilations were outselling Rolling Stones albums.

In the late 1970s, new production values started hitting the Brazilian music scene, influenced by disco as well as the tight, sunny grooves of Steely Dan and Earth, Wind & Fire. Disco music was a national craze, to the extent that the primetime telenovela (soap opera) was called “Dancin’ Days” – whose plot revolved around a club. Radio and nightlife were taken over by the 4/4 thump, while Brazilian artists such as Belchior, Rita Lee and Tim Maia embraced disco. Lesser known names covered American hits, such as the more recent Portuguese translation of Donna Summer’s “I Feel Love” resurrected by São Paulo’s DJ duo Selvagem.

Rio producer Lincoln Olivetti began making his mark by producing records for dancefloors. By the early 1980s, perfectionist Olivetti was Brazil’s number one producer, applying a synth-layered sheen to artists from Gal Costa, to Jorge Ben, to Almir Ricardi. As he distanced himself from his dance roots, he was increasingly accused of pasteurizing Brazilian music, making everyone sound the same. Nevertheless, the late Olivetti stands as a production and arrangement giant of Brazil, responsible for bringing music production in the country to a new level. A couple of years ago, Wax Poetics featured an online mixtape called Brazilian Boogie Boss with some of Olivetti’s finest productions.

At the same time, there was a lot going on underground. São Paulo by the early 1980s had the avant-garde samba jazz of Itamar Assumpção and the scene around the Lira Paulistana club to a variety of new wave/post-punk bands such as Fellini, Smack, Mercenarias and Patife Band, all featured on the recent soul jazz compilation, The Sexual Life of Savages. In the mid-1990s, the new manguebit genre had the country looking to Recife – where BR and Ballantine’s set anchor for Stay True Brazil – as bands such as Chico Science and Mundo Livre S.A. offered a new outlook on traditional-modern fusions, melding maracatu rhythms with rock, hip hop and electronic grooves.

When sampling culture took off in hip hop and dance music, the initial targets were mainly old soul, funk and disco tunes. However, producers were soon looking to go beyond the usual sources. Brazilian records proved a fertile ground for musical borrowing, especially samba beats. A famous example was Sergio Mendes’ “Fanfarra“, with a thundering samba break that on to be sampled in: The Goodmen’s “Give It Up“, Basement Jaxx’s “Samba Magic” and more.

For American DJ and producer Todd Terry, who also stars at Boiler Room & Ballantine’s Stay True Brazil event in January, Brazilian music has “always provided sources for percussion samples,” being a key element in his sound from the very start. Nevertheless, his classic tune “Samba“, credited to House of Gypsies, has nothing to do with the samba sound. “It’s more about the vibe”, Terry explains. Brazilian music in different shapes and sizes have appeared in music scenes around the world.

In the United Kingdom, Gilles Peterson was an early champion of Brazilian beats. In 2014, he released the Sonzeira project, featuring collaborations with Brazilian artists such as Elza Soares and Kassin. In Italy, the cult 1980s scene known as “afro-cosmic”, starred by Daniele Baldelli, was big on Brazilian tunes. In Japan, it is easier to find the catalogues of many classic artists from the 1960s and 1970s than it is in their homeland. Brazil’s electronic music scene came of age in the 2000s, when several of the country’s DJs and producers made forays into the global market. First of the list has to be Marky (with the aforementioned “Carolina Carol Bela” scoring him a Top 20 hit in Britain). Others include Patife, Renato Cohen, Gui Boratto, Wehbba, L_cio and Tropkillaz.

Miami bass and funk carioca

As of the 1980s, producers and DJs from Rio’s funk balls had begun incorporating music with electronic drums, mostly electro-funk and Latin freestyle. One particular beat, the “Planet Rock”-inspired 808 rhythm of Miami bass, proved especially popular. When Miami producers could not provide enough 808-bass music for the Rio crews, DJs like Marlboro and Ademir Lemos started making their own. Thus, Rio funk – or funk carioca or baile funk as we know it – was born. It spread like wildfire and was a national craze by the early 2000s, its crude lyrics purposefully offending many listeners. Soon enough, baile funk (actually the name of the dance events, not the genre per sé) was being exported by American and German DJs, with dedicated compilations released in both the States and across Europe.

Funk endured and fragmented as the decade progressed, with recent names as diverse as Anitta, Omulu and Leo Justi. The São Paulo funk scene has grown exponentially in the last ten years, spawning in later years a local variant called funk ostentação (‘ostentatious funk’) where kids from favelas celebrate a fantasy flash lifestyle of expensive clothes and throwaway cash. Its main exponent was MC Guimê who, previous to being discovered by mainstream Brazil, was already racking up an average of 40 million YouTube views. Funk ostentação is being replaced by a newer sound, where the money theme is replaced by themes of sex or violence.

Although some artists have reached the mainstream, the underground is still where a lot of the diversity and innovation in Brazilian music is at. Tahira has nothing but praise for Brazil’s current crop: “In the last five years, many interesting bands and producers have appeared. Musicians lost their prejudice against technology, and that opened the gates to a lot of good stuff.” Instituto’s hard urban grooves, Criolo’s cosmic hip hop, Tulipa Ruiz’ leftfield pop, Boogarins’ neo-psychedelia, Kiko Dinucci’s twisted samba, Bixiga 70’s revamped afrobeat, Bahia Sound System’s homegrown bass, DJ Dolores’ Pernambuco fusions – the list is endless. Brazil is a music nation that keeps on giving.

Head here for more info on our Stay True Brazil trip with Ballantine’s Scotch Whisky; and here to recap on all of the BR x Ballantine’s Stay True Journeys.