With the first weekend of the Football League action upon us, we examine a peculiarly under-sung alliance between the beautiful game and UK music.

—

As the nation’s sport, football remains one of the UK’s most marketable assets with the Premier League a significant and influential export. Despite this, football’s relationship with other forms of culture is difficult to identify. It’s almost non-existent in literature, film and theatre and in terms of music, has traditionally associated with rock.

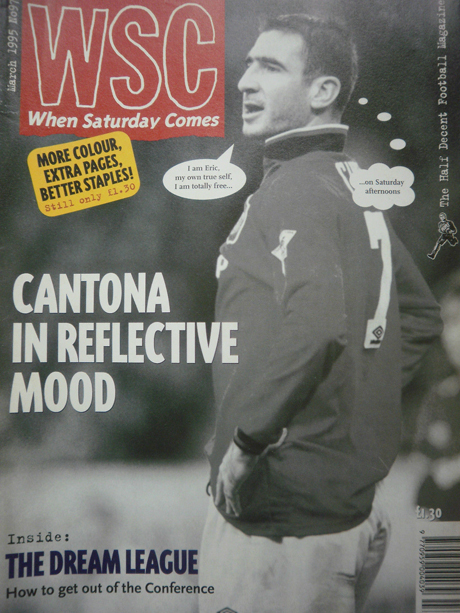

In the 1960s and ‘70s, footballers would rub shoulders with musicians in King’s Road nightclubs, while the iconic George Best could lay ownership to the title of ‘the Fifth Beatle’ for his effortless style on and off the pitch. With the dawn of punk came the rise of the fanzine, with DIY publications covering music, politics and football – often all at once. For instance, the self-described “Half decent football magazine” When Saturday Comes was named after a song by The Undertones and in its 29-year history has featured contributions from the likes of unashamed football obsessives John Peel and The Fall’s Mark E Smith.

Yet over the past few decades, it would be fairer to say a much closer relationship has developed between dance music and football. This was becoming obvious in the number of producers and DJs with a footballing background and in the music tastes of fans attending matches. Music critic Simon Reynolds points to the ‘Second Summer of Love’ in 1988/89 as a defining moment in dance music and football’s affiliation in the UK: “Football firms (warring gangs who supported rival teams) were going to the same clubs, but to everyone’s surprises, there was never any trouble. They were so loved-up on E they spent the night hugging each other rather than fighting”, he writes in Generation Ecstasy: Into the World of Techno and Rave Culture.

There’s escapism to be found both in the 90-minute football match and the rush of a DJ set, surrounded by likeminded people.

Clubbing provided an alternative to the terrace lifestyle for a generation of football fans; Reynolds goes on to talk about the “collective fervour, bodies pressed together, the liberation of losing oneself in the crowd”. It’s an effective comparison that captures the essence of a shared identity and the overwhelming euphoria that live sport and music can create. There’s escapism to be found both in the 90-minute football match and the rush of a DJ set, surrounded by likeminded people. That energy, a ‘fire-in-the-belly’ spirit, is also something which producers involved in the game have related to.

“Maybe that kind of energy that you have [as a footballer] translates into the energy you put in playing shows and the motivation you have to get things done”, says Mala, who was on Millwall’s books as a youngster before embarking on his music career. “My dad was always very much into football so it was something I grew up with”, recalls the dubstep producer. “It was a massive part of my life for much of my childhood”.

He credits football as one of the reasons he enjoys working in groups of people. “Working as a team is something still to this day that I prefer doing than working in isolation”, he says. “For me doing team sport is much more appealing and in a way, much more rewarding.” The proof of this is in the number of producers he has worked with over the past decade; both on his record label Deep Medi Musik and who have played his DMZ club nights. The camaraderie and teamwork that football imparts is clearly infectious.

Yet while it is fundamentally a team sport, it also incorporates elements of individualism. To be a top footballer, your brain has to operate half a second quicker than your opponent; the ability to spot a killer pass or try a piece of skill that others wouldn’t dare are what make certain players stand out. Darren Cunningham, the producer better known as Actress, was a professional footballer at West Brom before a series of injuries put an end to his career at the age of 18. He has spoken about how his skill didn’t come naturally to him, but rather was something that was honed through practice and perseverance.

“Both require a huge amount of discipline and devotion. There’s no way you can be a pro player and not give it your all from a very young age.” – Mala

“Mastery comes from practice. Start playing a sport and generally you can be quite shit at it, really”, he told Dazed and Confused in 2012. “I remember when I started playing football I didn’t know what the hell I was doing, I just started playing football and that was it and then I did something: I remember going and scoring this goal, it was a really jammy goal, and I kicked it and someone came and slid, tackled, and it looped off his foot, and the keeper came running forward, and it looped over him into the back of the net. And the euphoria I got from scoring my first goal was just unbelievable, and from that point onwards I just couldn’t stop scoring goals.”

He also talked of how the intensity of the professional game shaped his character in readiness for a career in music. “I am a footballer and I have been in environments where I am in rooms where there is a huge amount of testosterone going on and I have been in stadiums where a manager’s neck is on the line and the crowd is going ballistic at him outside the doors like literarily baying for blood. I have been in that situation where you have 20,000 people just like chanting or whatever”, he remembers.

Football and music are both forms of expression and in opening yourself up, you invite the criticism of others – as Actress witnessed himself. One genre in which this is particularly prevalent is grime, with MCs requiring a level of self-confidence to give it a go in the first place. Perhaps then, it is little coincidence that the genre has experienced plenty of overlap with football. The role of the urban landscape cannot be understated in this. From a young age, city-dwelling youngsters could mingle on communal football pitches at street level before to taking to the rooftops of surrounding housing estates to record sets on pirate radio.

Kano grew up down the road of West Ham’s ground Upton Park and was also a promising footballer in his youth, trialling out at Chelsea and Norwich. On “9 to 5” off his classic album Home Sweet Home, he told how he could’ve continued down that path but turned to grime instead.

“See I was supposed to be a footballer but they kept pickin’ the other kid who was a foot taller / I got lazy and less enthusiastic, I stopped trainin’ and turning up to matches / Started sub as the managers tactics but when I did play I used to score hat-tricks / Then I gave up now I’m in the music biz and I won’t ever let my laziness ruin this / There’s just no point, I’m on point, I’m the Henry on the mic, I’m so on point.”

Popular Football League defender and Nigerian international Dan Shittu was a keen DJ who helped Dizzee find his feet in the early days of grime.

Here Kano paints a picture that these were two very obvious professions that were open to him but his heart was more in the music; he’s content with being the ‘Thierry Henry’ of grime. That his cousin Jonathan Fortune did go professional at Charlton Athletic highlights the social ties between of grime and football. To name a few other examples, the late Esco was the half-brother of Jermain Defoe, while Trim is cousin to former Brighton and Swansea player Leon Knight.

Wiley, is a well-known football fan and Tottenham Hotspur supporter and his old bars are strewn with references to the sport. “50/50” includes the line “Used to kick ball with Lisbie” – a reference to the Hackney-born striker Kevin Lisbie, best remembered for his time at Charlton. Dizzee Rascal has also spoken in the past that he is indebted to Dan Shittu, who before becoming a popular Football League defender and Nigerian international, was a keen DJ who helped Dizzee to find his feet in the early days of grime.

It’s a point that was reiterated by Skepta, who started to notice a number of famous footballing faces in the audience at his shows as he started to make a name for himself in grime. “I always feel like the people who do music have got that thing where they think ‘if I didn’t do music, I’d probably do football’ so maybe the footballers do it the other way”, he told Soccer AM.

The rigour that both professions involve is a major similarity that Mala identifies with, although this is something few can really appreciate. “Both require a huge amount of discipline and devotion”, he says. “There’s no way you can be a pro player and not give it your all from a very young age. Very few people get into it late and become successful.”

“I remember getting rid of my bed to make sure I had enough space to put my studio equipment in. I used to sleep on a mattress that I used to put out on the floor to sleep at night time”, he remembers. “There’s a lot of things that happen before people are even aware of whether this is your talent. I think for footballers it’s the same as well. The level of devotion and dedication that they have to have just to sit on the subs bench, not even to get a game, just to be part of the squad…most people can’t deal with that.”

For those who do stick at football, the music is something you never really lose. With this in mind, when Jammer asked Yannick Bolasie and Bradley Wright-Phillips to take part in Lord of the Mics 6 last year, it seemed like the game had come full circle. Here were two professional footballers, returning to their first love of music, not for the exposure but because they wanted to. “When I was younger I used to be a grime MC. I’d been brought up around it and when I turned pro it was always the music I listened to for inspiration and motivation”, Bolasie told FourFourTwo. “When Bradley and me were at Plymouth, we used to send each other voicemails and videos.”

Interestingly, his most memorable bars were about what he knew best: football. He ribbed Wright-Phillips for falling out of favour at Charlton: “Looking bare eager couldn’t score goals in the Championship, that’s why he went down to League One – Brentford didn’t want him neither.” He also made a dig at his famous father Ian: “Just ’cos you got Wright in your name, don’t mean that you’re a Gunner”.

Grime succeeds as a genre because is it grounded in everyday life. MCs pick up references to what they see around them to embellish their lyrics, that we can either relate to or that can offer us a window into their lives. It’s fitting therefore that football should play just as big a part in grime as any other form of culture, given its place as a social phenomenon and a fundamentally British sport.

In what remains a time of political and religious apathy, football still has an overwhelming sway in public interest and regional identity. It maintains mass popularity both in the professional game but also at grassroots level, with 8.2 million adults participating in football in some form. Its appeal is in its universalism and its simplicity, that ‘jumpers for goalposts’ ethos. Grime too thrives off a certain rawness and the power of words. While many other art forms continue to overlook the ubiquity of football in the national conversation, grime will give it a voice.