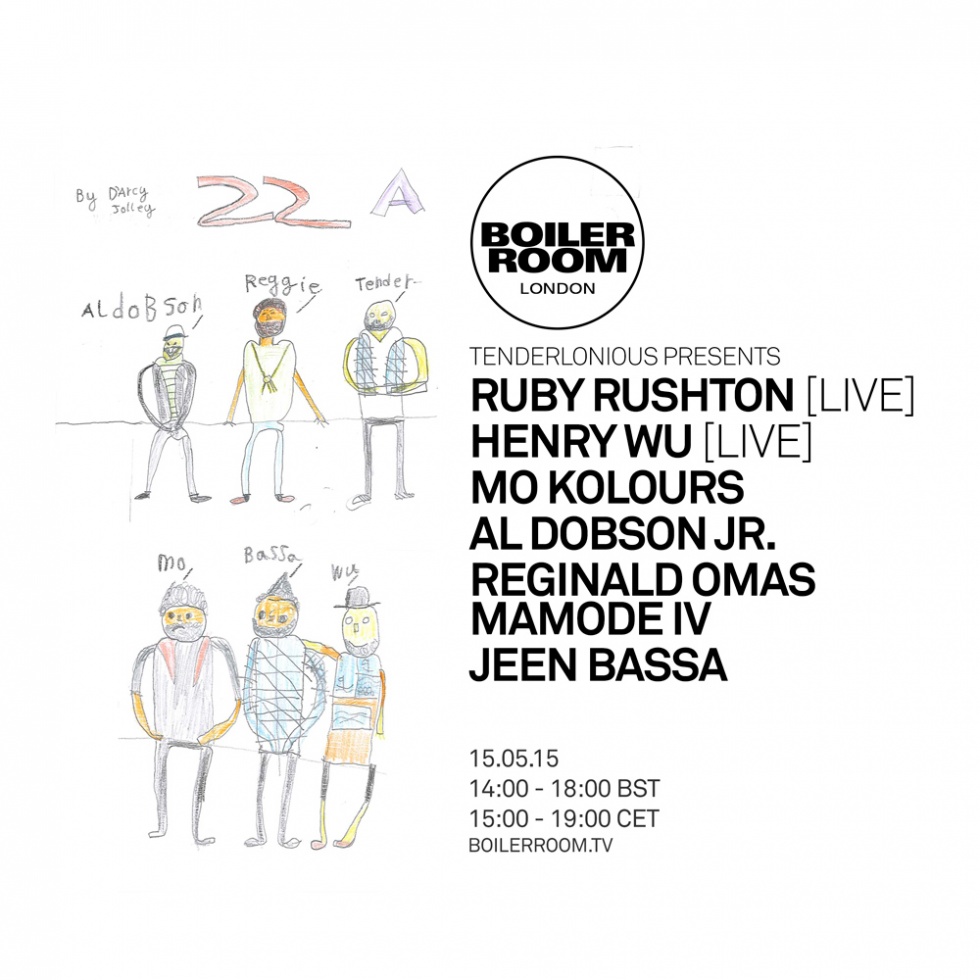

Towards the end of last year, DUMMY magazine put together an article about a loose collective of music makers from South London. The label in question was 22a Records and the piece was a longform introduction to their potpourri of soul, jazz and hip-hop influenced joy. It was well written no doubt, and for some people it provided a first glimpse at Tenderlonious and co. 22a exists as more than a collective, mind. Considering the fact that half of the guys responsible for releases are genuine family – Mo Kolours, Reginald Omas Mamode IV and Jeen Bassa are the Deenmamode brothers – the operation is more of an extended network of familia. There’s a laissez-faire feel about the whole exercise, no contracts are ever written out. Word is bond.

Along with Paul White, NTS’ Charlie Bones and Bradley Zero’s Rhythm Section club night and label, they’re sound mavericks on an imaginary axis curving down London’s east and into south.

One of the collective’s members was a ghost for the whole of that feature, mind; lightly mentioned in passing within paragraphs, yet otherwise absent. Henry Wu.

Contrary to his low profile approach, the 25-year-old beatmaker isn’t shy or a recluse. Something I found out when we met a couple of weeks ago outside Peckham Rye’s Sports Direct – newly purchased Nike slippers in hand and like me, craving lunch. He’s just uninterested in the glamour that surrounds music, and in particular, the celebrity status that can get velcroed alongside it.

“I’m still learning how to find that middle ground between doing what I want to do and not be so emotionally attached where I end up at the front of it.”

“Music is a fickle industry.” he explains, pulling up a chair by a homely foodspot serving Indian cuisine. The air’s pungent with aromatic ingredients, tickling the nose hairs with whiffs of coriander, chilli pepper and nutmeg. Peering over the counter, Henry orders two naans, a portion of mixed veg, some okra and dal. “You’ll look online and there aren’t that many pictures of me because I really don’t want to put myself as the face of it. I’m still learning how to find that middle ground between doing what I want to do and not be so emotionally attached where I end up at the front of it.” It’s the type of ideology shared by many inventors, who prefer to put their art first and faces way, way last.

Henry’s heritage is a rich factor in what he does. For a minute we divert into talking about French producer Onra and Chinoiseries, an album-cum-beat tape homage to Chinese and Vietnamese roots. Twisting his arm, Henry reveals a Chinese stamp-like tattoo; a stencil cut, circular-shaped motif designed by his grandmother. “My mum’s from Taipei, Taiwan – a really beautiful island just south of China. It’s just next to both Japan and China so there’s this mixed culture there.” From one periphery comes the forward-facing creativity of Japan and peering in from the other is China’s traditional culture. He’s a direct descendent of the Wu dynasty from the 12th or 13th century. “Shao Long means ‘little dragon’. That was the name that my grandmother gave me as a little nickname. I’m not really into tattoos that much any more, but I was just trying to connect with my history.”

Raised just ten minutes away from where we sit sifting through kidney beans, the basis of the Wu sound is tethered by old jazz, garage, grime and UK hip-hop as much as it is Oriental habits. Fond memories of Oxide & Neutrino’s Execute front cover and Choice FM’s Friday night special State Your Name show swell back into memory when talking about adolescence. Those were just on the minidisc though. Around the corner, Camberwell’s St. Giles Church was (and still is) home to a scantily promoted night called Jazzlive at The Crypt – a dimly lit bunker with a £5 entry and a penchant for live, free-for-all jazz sparring. Henry would be the youngest person in there without fail.

“My first instrument was the drums and I started playing percussion in primary school. I did that for a few years but then left that,” he adds. “Then I went to music college in Bermondsey, which was a community college and on the course I was playing drums but also starting to play keys when I was about 17 or 18.” At these times, producing wasn’t anywhere near the forefront. Session playing was the game, starting little funk bands with mates and essentially learning the craft. Splice any of the tracks occupying his Soundcloud and they’ll bleed Bob James, Herbie Hancock and Aaron Parks remnants.

Some would say it’s a very different London landscape nowadays. Gentrification has waved its wand over much of the area, attempting to nibble away at its enviable culture prowess. East and South London have been hit the worst. Take Southwark’s infamous Aylesbury estate – a brutalist titan that many will recognise from the Channel 4 ident. It housed around 7500 residents spread over a number of different blocks and buildings. A one bedroom flat is now about £600k in that same spot.

“I sold 80% of my equipment, and at the time I was just really disillusioned with the music – playing music is one thing, but the extra baggage is unavoidable.”

Similarly, Henry has gone through his own metamorphosis. As a session player for a particularly successful local songstress, he ended up alongside Tenderlonious, a supremely talented sax player. When the group went on to support none other than John Legend & The Roots, Tenderlonious entered the fray to beef up the horns section. Albeit a useful learning experience, the industry politics eventually got too much and at the start of 2012 Henry decided to quit music. “I sold 80% of my equipment, and at the time I was just really disillusioned with the music – playing music is one thing, but the extra baggage is unavoidable.” Islam would prove to be his moral compass.

“Religion plays a big part in my life, definitely. In Islam, there’s a term which explains the way we look at religion. Dīn describes a way of life as opposed to a religion. At least in the west, people see religion as something you do every Sunday or a weekly thing. It’s the foundation of my beliefs and that also translates to the music. I’ve realised that when you’re an artist, there is this whole understanding that people will follow your work.

“Idolising celebrities is a form of worship. That’s something that I don’t agree with. You should appreciate, but it should never be a thing where you’re really obsessed. You know how when Michael Jackson would come out of the car and people would start fainting? For me, that’s quite sadistic and a very dark side to being in the limelight. Being in the limelight is something that I’m very conscious of. Everyone is the same and I’m not better than anyone because I might be getting attention or someone might be paying me to go somewhere. I’m just in this for the music and to provide my family.”

His decision to return to music was a reactive one. At the end of 2013, Tenderlonious called Henry up and said that he was doing his own vinyl with Al Dobson; the embryonic stages of 22a. The whole crew were already vaguely connected, from different walks of life but PVA glued together by an admiration for African percussion, soul, J Dilla and the crevices in between. The Deenmamode brothers have Mauritian blood but originally came from Bristol and they went to uni at Camberwell art college. Henry remembers regularly pacing up to their flat where they’d be found headbobbing to beats made on an old eMac.

Many of them hadn’t even had wax out. Digital bits and bobs, yes. But it’s the 22a head honcho that really honed in on vinyl, putting some money together to create a home for their exploits. 22a just so happens to be the door number of the Tendelonious family home; an apt title. “That’s how I got back into it all because he came round to my house and there were these old beats from a couple of years.” He chose a few and said he wanted to put them out.”

Those relics would turn out to become 22a002.

The rest of 2014 would prove fruitful in multiple ways. The 22a release opened a lot of eyes to Henry’s talents. In 2015, Alex Nut’s HoTep imprint gifted the Wu with five tracks of dusty hip-hop-influenced, groovy cuts – the stand out being “Just Negotiate” featuring Simeon Jones’ lullabyish tones atop. Deeper into the year, there’s even more goodness planned on Rhythm Section International (Bradley Zero‘s burgeoning imprint).

For the guy that wants art at the centre of everything he does, Henry Wu is definitely doing things correctly.

—

Henry Wu will be playing a live set alongside the rest of the 22a collective. Check out the session page here.