Our team are heading out to South Africa for the next instalment in our global Stay True Journey with Ballantine’s Scotch Whisky, and preparing for a massive show that centres on the uniquely sophisticated house beats that form the heartbeat of the country. To get some understanding of just how important house music is for South Africans of all races and social backgrounds, we asked veteran local journalist Greg Bowes to give us a potted history.

—

“I wanna be free / from these chains that are hurting me,” Boom Shaka’s Lebo Mathosa sang in 1998. She delivered it over a slow but urgent house beat produced by Oskido, Christos Katsaikis and Don Laka. The music was known as kwaito, a combination of house’s rhythmic engine (in second gear) and colloquial commentary: the sound of a new South Africa.

When Mathosa was killed in a car crash on October 3 2006 it may have felt like an era as golden as her locks had ended, but she’d helped cement house music in the S.A. mainstream and the scene would shine in her wake. The Mzansi [colloquial, Xhosa-derived name for South Africa] house train had left the station, its momentum was unstoppable, and now in 2015 names like Black Coffee and Culoe De Song are internationally lauded.

The sentiment of Boom Shaka’s song neatly sums up South Africa’s house story, which blasted into life four years earlier when Mathosa first hit stages and shocked airwaves. Boom Shaka, an overtly pop-skewed four-piece which also featured Thembi Seete, Junior Sokhela and Theo Nhlengethwa, rocketed to fame when she was just a teenager, and they had massive hits with tracks like “It’s About Time” and “Thobela”.

The sound was sluggish, built for beer rather than E, and celebratory. It was international house music cut with the colloquial vocal sentiments of an optimistic South Africa that just wanted to feel liberated. Central to the birth of kwaito – a genre which, perhaps ironically, got its name from the Afrikaans slang word “kwaai” meaning cool or new – was a former Mr. Soweto, Arthur Mafokate, who had re-appropriated, much like rappers in America, the Afrikaans insult “Kaffir” in 1993. The track “Kaffir” (“Nee baas [No boss], don’t call me a Kaffir.”) was a huge hit and signposted new avenues: Mandela was free and soon the people would be too, and there was an air of anticipatory celebration across the country. Its soundtrack would be the soulfully-grinding, forward-moving kick of house music.

Mafokate got his first break earlier in 1993 producing a few volumes of the cassette series Groove City along with Tim White, for which the term “knock-off” might be too kind. With a track titled “Luv For Luv” (a cover), the intentions were clear: take the xylophone/organ house Robin S was killing clubs with and give it local flavour. In most cases this was by redoing the tracks in the way they were being heard at clubs and in the township’s drinking spots, the shebeens: pitched at anywhere between minus two and minus eight.

Couth was in short supply on these cassettes: the In The Groove tape, also credited to Mafokate and White, arrived with the Nervous Records logo emblazoned across the cover (the connection to the NYC label is unclear to say the least), but at least made room for songwriting credits for the (mostly Italian) originals. These tapes, and others like the Mixmaster series helmed by future heavyweight Oskido (pictured above), were essential to a burgeoning house music scene: they made the music that heralded the end of Apartheid available to a wider audience, for whom cassettes were common and CDs were high-end. I bought my copy of Into The Groove for 15 Rand: less than £1.

Tim White, now a DJ and label head for House Afrika, who plays a major part in this story, remembers, “We had no idea about licensing – we hadn’t even thought to reach out overseas to license a song – but these tracks were popular, so how do we get them out on cassette? We needed studios.” Oskido had already hooked up with jazz muso Don Laka; White came across the 18-year old Arthur Mafokate at Jewish-owned Shandel Music and they set about recreating his favourite international tunes.

Toyota Microbuses (“Caracara”) doing runs to the townships held a captive audience for house music

“[We] were taking the big international house tracks, referencing them and doing our own slowed down versions of them: slightly African-ised, ripping a bassline here and there, so they were kinda cover versions but originals at the same time… During that whole process – ‘OK, let’s do it like this’, maybe adding a local snare – they were kind of getting a natural local influence. We were putting them out on cassette and selling them like fucking hotcakes out of the boots of our cars to various distributors around the country.”

One-stop warehouse shops like Reliable Music in Jozi and Dakota in Pietersburg (now Polokwane) were where informal traders or hawkers were getting their music. White reckons they sold 80,000 copies of the first Groove City, mainly from these stores, but it was another fast-growing sector of the new South African economy that would provide the ultimate marketing tool for early takes on house: taxis. Toyota Microbuses (aka the “Caracara” – also the title of 2014’s skhanda rap / new age kwaito breakout anthem by K.O.) were doing runs in and out of the CBDs and to the townships (accompanied by a bizarre vocabulary of cryptic hand-signs that serve in place of any kind of official labelling of the vehicles) and they held a captive audience for house music.

Sold by an army of hawkers and taxi-drivers, these cassette series and others blurred the boundaries between covers, originals and homage. Others included Vision (Quentin Foster), Deep Evolution (Pete “Boxman” Martin with a cameo from future kwaito star M’du Masilela), plus work from Gabi Le Roux (who also recorded for the Groove City series and produced for a number of kwaito stars) and Jacknife, who all created sub-Saharan sweetness from familiar house tropes and sold massively. Ironically many of the producers at this stage were white and privileged – making music for sardine-squashed black commuters.

Some international licensing deals did materialise, and compilations of the work of Chicago’s Larry Heard, Miami’s Murk Productions (Funky Green Dogs, Interceptor, Liberty City etc) and Detroit’s Kevin Saunderson (aka Inner City and The Reese Project) signalled the future-facing optimism of a country leaving dark days, as well as just how cultured S.A. tastes were.

The chugging thump of house music was fitted with vocals in vernacular that connected directly with audience

After the initial success of these tapes, the chugging thump of house music was fitted with vocals in vernacular that connected directly with audience and kwaito quickly overtook cover versions as the dominant form. New acts seemed to arrive on a daily basis from the mid-Nineties, and included Aba Shante, Skeem, Chiskop, Bongo Maffin, Alaska, TKZee and many, many more.

One label stood head-and-shoulders above the pack in the kwaito and S.A. house game and continues to remain there: Kalawa Jazmee. Named for founders Christos Katsaitis (Ka-), Don Laka (La-) and the inimitable Oscar “Warona” (Wa-), Kalawa collected together the brightest beat-makers, singers and sessionists around at the time and set them to work on a colourful ensemble of early kwaito acts.

Katsaitis (pictured above; he’s seemingly written out of the Kalawa story in their digital space, since he departed in 1995) was a DJ of Greek descent who was spinning in upmarket, mainly white, nightspots like Caesar’s Palace in Braamfontein, where he met future partner in rhythm Vinny Da Vinci. Laka was a jazz pianist with serious chops and an eye for the floor. Oscar aka Oskido was selling boerewors (a spicy local sausage) outside Club Razzmatazz in Hillbrow when their DJ failed to pitch, and his massive personality and enormous tracks made him one of S.A. house’s pioneer spinners.

Among the acts the label thrust into the mainstream were Lebo Mathosa’s Boom Shaka, Trompies (who styled themselves on the township tsotsies – thugs – with their hats and All-Stars and danced in the sharp Pantsula style), the more sedentary Alaska and the generous Thebe.

The label was also home to Oskido’s act, alongside Bruce “Dope” Sebitlo, Brothers Of Peace. They were the first S.A. house act to gain notoriety outside our shores via a hook-up with “Little” Louie Vega, who first visited S.A. in 1999, where he played to a warehouse full of adoring fans. His MAW Records imprint initially released the duo’s work on Mafikizolo’s “Loot” (a derivative but hella catchy nod to samba house), then BOP themselves, with “Zabalaza” and accompanying Masters At Work remixes arriving a year later.

Kalawa is not only still around, but it’s probably probably still the most relevant local label. Mafikizolo is now a duo – after the group survived a collision with a train, founding member Tebogo Madingoane was killed in a road rage incident in 2004 – and they are a slick Afro-pop act with three South African Music Awards for Best Group to their name. They’re backed by the considerable production prowess of Uhuru (check their infectious Portuguese-flavoured collabo with Angola’s Yuri de Cunha, Oskido and DJ Bucks, “Y Tjukutja”). Meanwhile their label-mates Black Motion are on the bill for the debut Jozi edition of Boiler Room after conquering Miami and more, as well as raiding national charts with their super-charged tribal house.

While kwaito ruled the nation into the new millennium, a more purist house was still being nurtured in the townships on Sunday afternoons at numerous “chisa nyama” braai (BBQ) joints and in the clubs, mainly those in Pretoria, by DJs like Christos, Vinny, Ian Segola, Positive K and Bob Mabena. Spots like the legendary Gemini, Cherry’s and later Carnalita and Ellesse still inspire awe-struck reactions from those who were there. But the music was almost always international.

Vinny and Christos had some success as DJs At Work, while DJ Mbuso’s “Mdali” was picked up by Charles Webster for international release on his Miso label. More considered acts like Jazzworx and Revolution stepped the gloss up a notch with their studio skills, but the heads (and by that really I mean most of S.A., still the largest house music market on the planet) were getting down to grooves laid down by the countless overseas DJs who followed in Vega’s wake: Frankie Knuckles, Dennis Ferrer, Rocco, DJ Gregory, Alix Alvarez, Mr V, Alexkid, Frankie Feliciano, Kenny Dope, Franck Roger, Jojoflores, Jef K and many others.

To cater for the crowds queuing outside these spots and devouring the house tunes laid down by Thato “DJ Fresh” Sikwane on newly-formed regional radio station YFM in 1997, House Afrika jumped into the compilation game again. The label had been founded on the profits generated from early cassette releases by Tim White and his wife Dana, G-Force (a DJ who’d done duty in the country’s first rave club, 4th World) and then-promising spinner Vinny Da Vinci.

“I went to America [in 1994] and met a few wholesalers over there,” White recalls. “We opened the first shop in Hillbrow. We didn’t like the location [the area is notoriously dangerous] and wanted bigger premises, so we bought a house in Orange Grove and moved down there in ’95, ‘96”. The shop was a mecca for DJs until 2008, “the end of the vinyl era,” but the store lead to the label.

If anyone was in doubt about how well-schooled the average S.A. house lover was even then, double platinum sales squashed the misgivings

“[The shop] was our sounding board for the top tracks, and again it was a question of ‘how do we get these tracks out to the people, to the greater world?’ The music was only available on vinyl in a few select stores and it was very expensive; the bulk of South Africa was buying music on CD, so we started licensing stuff. For Fresh House Flava Vol. 1 we licensed twelve tunes and boom: the thing went on to sell 114,000 copies.”

The first DJ Fresh-fronted Fresh House Flava disc (and cassette!) included a trio of to-die-for Mood II Swing classics (including their melancholy take on “Mysterious People”) and cuts by Charles Webster’s Presence and Chez Damier. If anyone was in doubt about how well-schooled the average S.A. house lover was even then, double platinum sales squashed the misgivings. And if there’s any doubt about their continuing influence, new generation star Okmalumkoolkat says those DJ Fresh tapes “are all there in my memory box, I can’t take that away. If you play any track from those compilations I’ll cry sometimes!”

Culoe De Song (pictured above), who’s also playing Johannesburg’s Stay True Boiler Room gig, says, “The house music community here has always been open-minded,” and remembers DJ Christos coming down to play in his home town of Durban and amazing crowds whilst still introducing new music, stuff that was new and different – not just playing the hits.

Volume 2 of Fresh House Flava continued in 1999 with Blue 6, Glenn Underground and Herbert all making appearances. In 1998, Vinny Da Vinci helmed the first Deep House Sounds CD, and kicked off his mix with Matt Herbert’s re-lick of Moloko’s “Sing It Back”. Oskido trumped them all though with the intro to the debut release in the Oskido’s Church Grooves line: a minimal spoken word from fellow YFM DJ Shabba into Aztec Mystic’s “Jaguar” – at a crawling pace, but still confounding. BOP’s “Together” followed, a shameless coupling of Thomas Bangalter and DJ Falcon’s filtered French disco as well as that damned ubiquitous Robin S bounce.

Both the Fresh House Flava and Deep House Sounds series stretched into ten volumes and spawned plenty more mixes and compilations on other labels like SoulCandi, currently home to prominent S.A. producers like DJ Whisky, Kid Fonque and South Africa’s biggest house act, Mi Casa.

In the mid- to late-2000s, South African house really started to find its feet. According to Culoe it was “when local house started embracing the African concept, and the music started getting licensed internationally. We evolved from being a nation of imports. We had a sound that was only coming from here and people were asking, ‘What’s that?’” He cites Black Coffee’s remixes of more traditional South African artists like Busi Mhlongo and Hugh Masekela – which also caught the attention of Louie Vega, who licensed it to his Vega imprint – as making a difference. “You’re getting a taste of what you know,” he adds. “But with more local flavour.”

The DJ Unite crew of DJs Fresh, Oskido, Vinny Da Vinci, Christos and Kaya FM’s Greg Maloka (pictured below) – a fine DJ who heads up “Afropolitan” radio station Kaya FM, where Ralf GUM is as likely to boss the Top 40 as Aloe Blacc or Gregory Porter – started hosting the S.A. Music Conference. A series of talks and workshops, it exposed kids eager to produce to the genteel advice of Vega, Webster and more, and they must have convinced quite a few that all it took to be a house artist with a catalogue on Traxsource was a computer and some desire.

Other international friends did their bit to propel South African house onto the international stage. When I speak to Devon producer Andy Compton of The Rurals, he’s about to embark on his fifteenth tour of the country and jokes that “it’s the only place that seems to like my music – it’s crazy!” Rurals tracks had been compilation staples for years, but Compton’s first trip here was only in 2011. Bitten by the S.A. house music bug, he released Kholofelo Remixed a year later, a compilation that shone a light on local talent like Da Capo, Darque, DeepXscape and LIPS. He subsequently set up the Peng Africa label to further excavate S.A.’s rich rhythmic seams.

Compton is not the only one calling South Africa a second home: Germany’s Ralf GUM generally has the work permits to prove it. He’s been visiting since 2008, and while his coolly-clipped production work alongside vocalists like Monique Bingham, Caron Wheeler and Robert Owens often have S.A. listeners and dancers in rapture, his GOGO Music label has also taken local talent to the floors of Europe and the US, with releases from Black Coffee (and his previous act Shana), 60 Hertz Project and singer Bucie.

“[South African artists] brought a fresh new sound to [house],” Ralf tells me. “It’s more a feeling – you can’t really define it. It’s a soundscape that gives the music a special kind of life that didn’t necessarily exist before in house music. It gives the music a unique feeling.”

In the noughties a number of other international labels had their A&R ears piqued. Germany’s Compost had pastoral electronic impressionist Felix Laband on its books and soon the brutal, kwaito-inspired funk of “Donkey Rattle” (2002). Warp licensed DJ Mujava’s “Township Funk” in 2009, while Spoek Mathambo cohort (and bandmate in Fantasma) DJ Spoko and Wigan import Jumping Back Slash have advanced the “gqom” sound, which originated (alongside the use of “qoh”, ecstasy) in the townships of KZN.

This overtly bleepy variant of local house, and the leftfield leanings of the likes Mathambo and fellow musical polymath, Okmalumkoolkat who made inroads into the UK bass scene through collabs with LV, was matched by less strident songs by the likes of Black Coffee, Liquideep and C.9ine, and a fully-formed original S.A. house scene had arrived. Realising this, local labels have beefed up their S.A. contingents. “There’s no lack of quality at the moment,” says Tim White. “We’re missing some songwriters, but South African house is in a very good state. 90% of my repertoire going forward is local.”

Compton concurs: “There’s this deep house sound that I really like; it has a real rawness, a naïve sound that makes it special,” and he tips the likes of Sir LSG for future success. Other acts making inroads include Jullian Gomes (who released a collaborative album with the UK’s Martin “AtJazz” Iveson in 2013), Jazzuelle, Echo Deep and countless others.

Although he hasn’t released any music in a couple of years, the former recipient of a RBMA Sónar, Black Coffee, continues to be a touchstone, and has attempted to seal his stature with grand gestures like performing his hits with a 24-piece orchestra for the AfricaRising project. He’s now consistently in demand, constantly on the road, in Barcelona one day, London the next, and clearly an inspiration to aspirational youth.

Culoe De Song is not necessarily a name you hear on South African radio too much, but his hefty releases for the likes of Mule Musiq and Innervisions lead to regular overseas bookings. Trancemicsoul is another underground hope and just made a Fabric debut on a T.Williams-compiled bill. The South African house vibe has also struck a chord in other African countries, particularly Nigeria, where the 120 BPM tempo is favoured in most nightspots. The influence can be felt in tracks like D’banj’s 2012 UK Top 10 hit “Oliver Twist”, Davido’s “Skelewu”, P-Square’s “Alingo” and that same act’s hook-up with May D and Akon, “Chop My Money”. This has been partly achieved because most Nigerian music videos are shot here, but reciprocally Mafikozolo have toured that country and concocted hit “Happiness” with Naija’s May D. This fruitful cross-continental activity looks set to continue apace.

While South African house music continues to flourish, a lack of marketing may have harmed the chances of some of these lesser-knowns, and hopefully pieces like this go some way to addressing this. In South Africa the fervour is undiminished, and perhaps that’s because it’s been a constant since the early ‘90s. We have just as many problems as we had pre-’94 – crime rates are spiralling, corruption is endemic, our Parliament is a mess, service delivery is flawed and the divide between rich and poor is ever-widening – but there’s always an ecstatic supply of positive dance music available on tap in taverns, on TV and just about every radio station.

Freedom might be more of an ideological concept right now than an everyday reality, but it’s alive and well on South Africa’s dancefloors. “House here has always been about that freedom,” says Culoe De Song in conclusion. The form birthed in Chicago and raised in the clubs of Europe has been adopted by South Africa as its very own. And it’s not leaving any time soon.

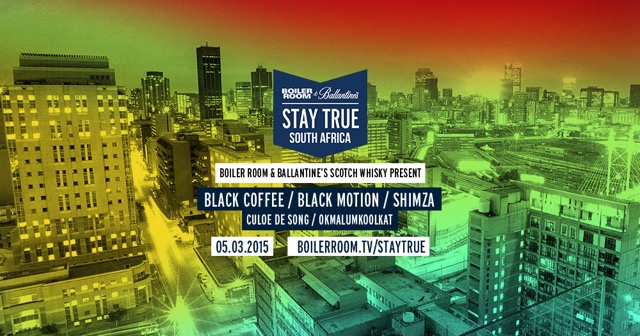

Our Ballantines Scotch Whisky Stay True broadcast from South Africa takes place on the 5th March with Black Coffee and a crew of equally talented musicians: find out more via the session page here.