Q&A: Selectorchico

A country with an enviable artistic and political standing maintains its modest identity serving as a musical bridge and consul between the southern hemisphere of the continent; a latent yet critical tip-top space for the cultural traffic in South America’s extensive music clutter.

The Oriental Republic of Uruguay, a place that would seem to hold all sorts of vanguard regarding social and ideological matters captained by the last hero of politics, seems to conserve its small town and tranquil amenity even throughout its major cities and active nightlife. Under this coat, Uruguay shines as the most socially developed country in South America clutching press freedom, income equality, legal marihuana consumption, lack of corruption, religious freedom/secular government, and musical crossbreeding; inevitably inspiring.

Sharing borders with Brazil and Argentina, some of the most important dance music harvesters and artist nests of the American southeast, Uruguay seems to pierce through the jumble in a very peculiar way. One of the key colors of Uruguay’s root sound was marked by the slave migration of the Bantu African culture to the country, which led to the rise of the Candombe genre that is still very present in Uruguay’s current carnivals and festivities; now serving as social protest through ostensible healing/therapeutic dances. Throughout modern history Candombe and other native genres like Murga and Milonga have flourished to become world heritage boons for the country and influencing some of the prime movers of electronic music in Latin America. The piano drums, Chico snares, and repiniques have evolved into 808 cuts, hazy synthesizers, and political speech vocal samples, marking a swingy and humanized aesthetic on the folkloric re-works of artists like Selectorchico and Lechuga Zafiro. Zafiro describes this Frankenstein mirth as “danceable science fiction with a Latin-American identity”. Discernibly, the old Payada de Contrapunto singing sessions have been reshaped by the local beat poet virtuosos into extended DJ sets that claim Uruguay’s strong inclination to ebullient dancing through Techno, Cumbia-bass, and Subtropical music. These results have caught the attention of label owners from neighboring cots like Argentina, who are intrinsically influenced by Uruguayan culture because of their regular booking schedule like Federico Molinari, who has been landing release slots for local producers like Federico Lijtmaer on his celebrated label Oslo.

In addition to the rich local produce, the country’s paramount musical cities in the praiseworthy CONOSUR territory like Montevideo and Punta del Este have been a hotbed for world conquistador conveyors like Mark Barrott’s International Feel label, which has served as a platform launcher for foreign projects like DJ Harvey’s Locussolus and Argentinian disco lord Fernando. It is clear that the synthesis of rich musical embodiment and liberal political assets have come to unveil acme musical results via local and foreign artists, magnetizing the constant flux of club enthusiasts from Europe, Argentina, Chile, and Brazil in both the capital and the country’s musical beachfronts.

A critical area where these quality floor-filler heaters shimmer is in Punta del Este, a spot home to the haunt monde audience and anxious club-goers in the Maldonado region where Boiler Room will debut its very first Uruguayan session with a lineup in charge of the Subtropical mastermind Selectorchico, Oslo label founder Federico Molinari, and Nicolas Lutz playing back-to-back with DJ Koolt; a carefully curated roster to represent both re-interpreted folklore and blended styles that circulate around the country.

Selectorchico squeezed in some time to answer some questions regarding his very own Subtropical concept, Uruguay’s governmental policies, and an insightful lecture on South America’s new wave of modern vernacular producers.

BR LATAM: It is clear that Selectorchico is a project influenced by various cultures like the one present in Uruguay, your Swedish nativity, and Jamaica’s dub textures that are very present in your music. Referring those influences, how and why was this project conceived?

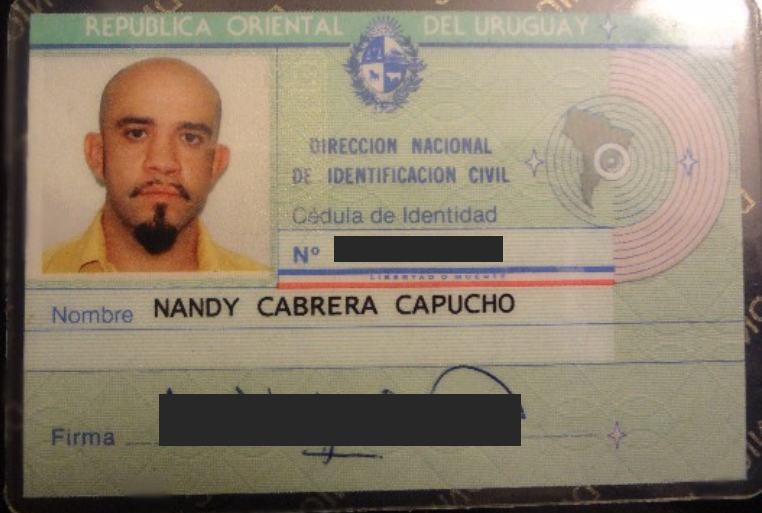

Selectorchico: Being the son of political refugees, the migration experience is very central for me and makes me who I am. I look for an ambiguous and hybrid sensation in the music that I produce and play from different sources, eras, and styles. For me, Dub is more of a method of work than a style per se. It is the manipulation of space-time: the reproduction of a sound being a part of an integral musical language, the polyrhythm, the echo and reverberation as aural images, the spectral resonance that denies lineal time. In a political sense, I think that the subversive metaphors suggested within Dub are what interest me the most. Selectorchico was born almost 20 years ago as a necessity of Nandy Cabrera; at first being a guest MC for the band Plátano Macho (1998), and then as a remixer and beatmaker.

What do you think is the central essence of Subtropical?

Subtropical is a term I found in a geographical atlas that alludes to climate. I do not perceive Subtropical as a unique genre; I think it is more of a marginal position facing continental and Caribbean culture. Uruguay is in a relatively isolated zone and both the tropical and Afro music that is played in this part of the continent has a yearning feel with a strong sense of identity that is always in relation or referring to Africa or the Caribbean. This comes from musical crossbreeding, the transatlantic influence blends, and the deterritorialization of identity.

You just put out a mixed compilation entitled Revisitando Macondo Vol. 1 – The Roots of Subtropical Music. How was this mixtape curated and for what reasons?

Throughout the years I’ve been buying many second-hand vinyl records and discovered the label Macon through the sale section of the Tristán Narvaja fair. I discovered a bunch of music that was edited throughout the 70s via this label. The music that I found was incredible because the mix of popular styles in other countries like Puerto Rico/Cuba (Plena, Guaracha, Bugalú) and Colombia (Cumbia, Bomba, Porro) with a unique approach. The influence of the Afro-Uruguayan Candombe rhythm is very preponderant. The sound is raw, hard, and almost garage. Both the original compositions and the preexisting versions are dazzling. Once I bought around 30 LPs, I spent my time digitalizing and re-mastering them, followed by selecting the most relevant tracks and taking them to a public that might not know them.

You curate a recognized party in Uruguay called Club Subtropical. Could you tell us more about it?

Club Subtropical is a space created by my colleague Nectar and myself in 2010 to accommodate the music that we liked back then (and still love now) and to regularly conjoin the music we felt that wasn’t represented in Montevideo’s scene. Maybe the most important aspect was to create a platform that can now host a bunch of producers and artists that we want to hear and foment the musical exchange by presenting their sounds to a new audience. I am talking about artists of the new wave of Cumbia from BSAS like Che Cubé, DJ Negro Dub, Peco Kumbia Style, or precursors like Zurita, Diamante and Remolón, and creators which fusion folkloric aspects with beats like Chancha Via Circuito and Barrio Lindo. There are also producers from a more distant horizon like Débruit (France) o Chief Boima (US/Sierra Leona) and women MCs like Miss Bolivia and Sara Hebe that have debuted in our country with the help of our collective. Club Subtropical is currently ran by Sonido Superchango, Selector Nectar, Lechuga Zafiro and myself. We have also invited many other local talents like Proyecto Mestizo, Vaimaca Dub, Jaime Roots, Malabizta, C1080, etc. There is also a stable repertoire of collaborators in the visual and graphic fields like Sr. Estampador, Sebastián Alies, and Fede Racchi.

How are the opportunities of the genres linked to modern autochthonous sounds like Subtropical and Cumbia-Bass regarding labels and promoters in Uruguay?

Nowadays, I try to think more in terms of networking. I’m about to release an EP with DUB GARDEN (Canada), who I contacted after releasing my remix of Amdet (Cooptrol). I am also releasing alongside Pangolin Sound System a batch of remixes and tracks that include the voice of my father, the poet Sarandy Cabrera (1923 – 2005) on Peruvian net label MATRACA. Regarding the project Revisitando Macondo, I can now announce that I am on a compilation for a big international label on vinyl sometime in 2015.

How have the liberal policies present in Uruguay influenced you and the artistic scene?

I think they are positive because they are initiatives that were born in the civil society. I am very critical regarding other policies that have not been implemented and that I think are more important: truth and justice for the victims of terrorism from the state of military dictatorship, an environmental policy that could vanish the mega agriculture corporations like Monsanto (which have ruined our fields and water), the acknowledgement of the Charrúa ethnocide, etc. The policies that you mention are perceived differently both inside and outside the country.

You also collect and create mash-ups with Latin rhythms blended with vocal samples from international artists like Santigold in a Bootleg format. With what artist would you like to collaborate in a hypothetical future?

To name a few: HR from Bad Brains, Bill Laswell, Martina Camargo, Mike Patton, dub poets like Mutabaruka or LKJ, Gnawa musicians from Morocco, Le Trio Joubran from Palestine, Dominican MCs from Denbow like Pablo Piddy and Milka. I would also like to collaborate in the design for soundtracks from directors like Katsuhiro Otomo, Ari Folman, Jodorowsky, and cyberpunk science fiction authors like William Gibson. Also, great exponents of P-Funk like Bernie Worrel, Bootsy or Clinton, musicians of the golden tropical age in Uruguay like Mario Maldonado, Eduardo Da Luz, Carlos Goberna, Chico Ferry and Arrascaeta, pioneers of the electroacoustic music like Pierre Henry, Terry Riley, Afrobeat geniuses like Ebo Taylor and Tony Allen, the list is long…